By Jim O’Neal

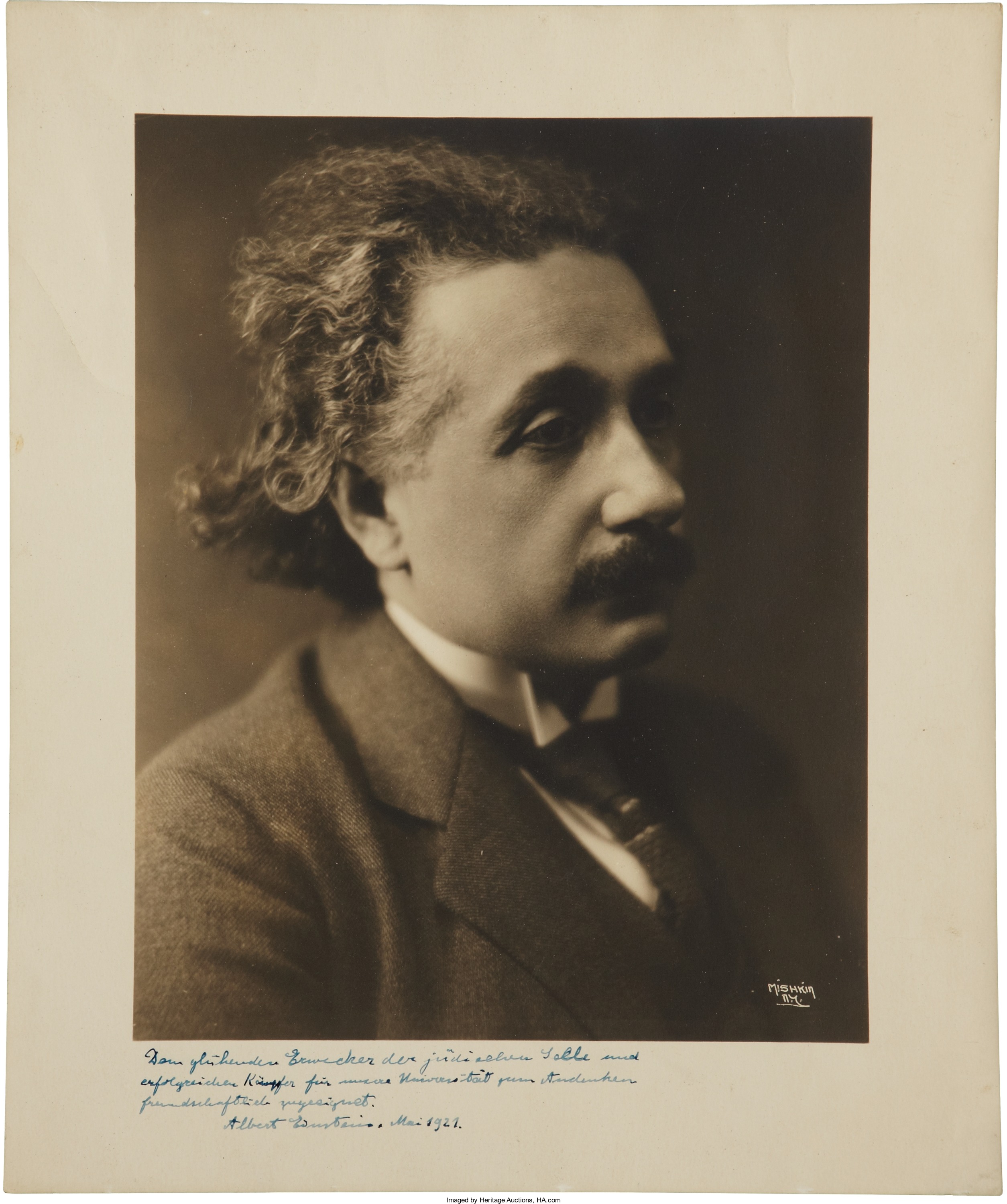

Serious writers about Albert Einstein almost invariably include two episodes in his life. The first is the year 1905, when he published four stunning scientific papers. The first explained how to measure molecules in a liquid; the second explained how to determine their movement. The third was a revolutionary concept that described how light rays come in packets called photons. The fourth merely changed the world!

A second highlight deals with a “fudge factor” Einstein (1879-1955) called a “cosmological constant,” whose only purpose was to cancel out the troublesome cumulative effects of gravity on his masterful general theory of relativity. He would later call it “the biggest blunder of my life.” Personally, I prefer a much more simplistic observation that perfectly captures his nonchalance. The poet Paul Valéry (1871-1945) once asked him if he had a notebook to keep track of all his ideas. A rather amused Einstein quickly replied, “Oh, no. That’s not necessary. It is very seldom I have one.”

History is replete with examples of people who had a good year. It was 1941 for Yankees great Joe DiMaggio when he hit in 56 consecutive games, and Babe Ruth’s 60 home runs in 1927. For Bobby Jones, it was 1930, when he won all four of golf’s major championships. Some people have good days, like Isaac Newton when he observed an apple falling from a tree and instantly conceptualized his theory of gravity.

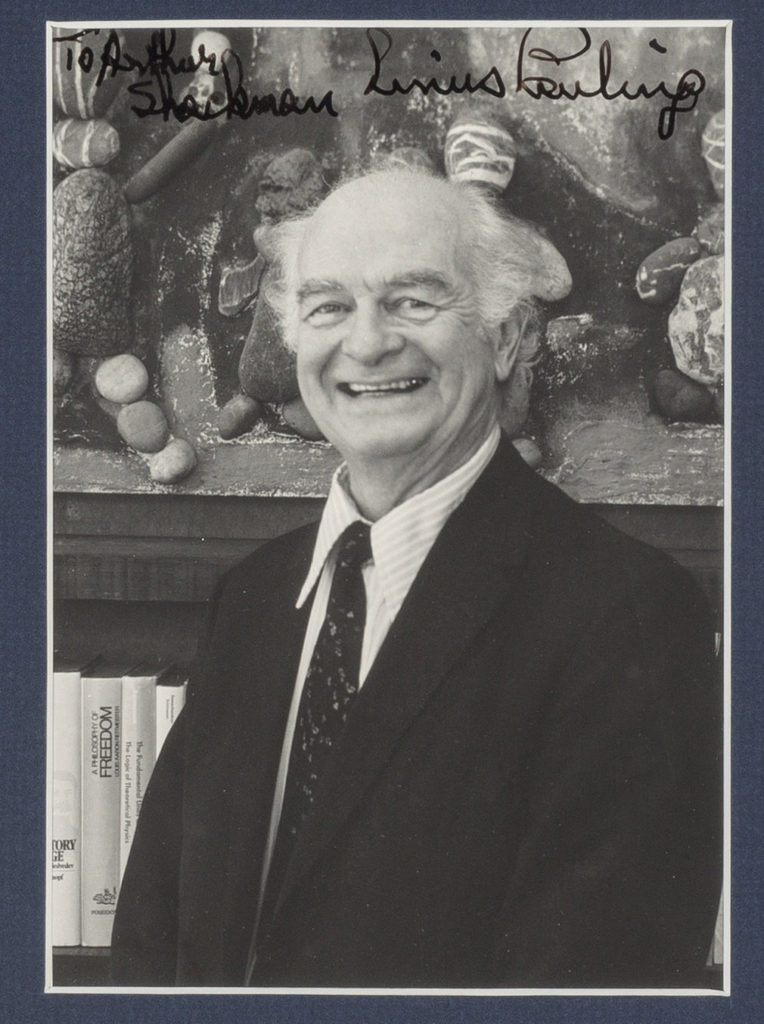

Linus Pauling was different. His entire life was filled with curiosity, followed by extensive scientific research to understand the factors that had provoked him to wonder why. Pauling was born in 1901. His father died in 1910, leaving his mother to figure out how to support three children. Fortunately, a young school friend got an inexpensive chemistry set as a gift and that was enough to spark Pauling’s passion for research. He was barley 13, but the next 80 years were spent delving into the world of the unknown and finding important answers to civilization’s most complex issues.

He left high school without a diploma (two credits short that a teacher wouldn’t let him make up), but then heard about quantum mechanics and in 1926 won a Guggenheim Fellowship to study the subject under top physicists in Europe. (He was eventually given an honorary high school diploma … after he won his first Nobel Prize.) By the late 1920s and early 1930s, Pauling was busy cranking out a series of landmark scientific papers explaining the quantum-mechanical nature of chemical bonds that dazzled the scientific community.

Eventually, he returned to the California Institute of Technology (with his honorary high school diploma) to teach the best and brightest of that era. Robert Oppenheimer (of the Manhattan Project) unsuccessfully tried to recruit him to build the atomic bomb, but failed (presumably because he also tried to seduce Pauling’s wife). However, Pauling did work on numerous wartime military projects … explosives, rocket propellants and an armor-piercing shell. It’s a small example of how versatile he was. In 1948, President Truman awarded him a Presidential Medal for Merit.

In 1954, he won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his research on the chemical bond and its application to the elucidation of the structure of complex substances … which I shall not try to explain. And along the way, he became a passionate pacifist, joining the Emergency Committee of Atomic Scientists, chaired by Einstein, in an effort “to warn the people of the pending dangers of nuclear weapons.” His reward was to be called a communist; he had his passport revoked and his patriotism challenged, along with many others, in the dark days of McCarthyism.

In 1958, he petitioned the United Nations, calling for the cessation of nuclear weapons. In addition to his wife, it was signed by over 11,000 scientists from 50 countries. First ban the bomb, then ban nuclear testing, followed by a global treaty to end war, per se. He received a second Nobel Prize for Peace in 1963, but that was for trying to broker an early peace with Vietnam, making him one of only four people to win more than one prize, including Marie Curie in 1903 (physics) and 1911 (chemistry). His other awards are far too numerous to mention. As an aside, he died in one of my favorite places: Big Sur, Calif., at age 93.

Sadly, in later life, his reputation was damaged by his enthusiasm for alternative medicine. He championed the use of high-dose vitamin C as a defense against the common cold, a treatment that was subsequently shown to be ineffective (though there’s some evidence it may shorten the length of colds). I still take it and see scientific articles more frequently about the benefit of infused vitamin C being tested in several cancer trials.

If he were still working on it, let’s say the smart money would be on Pauling.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].