By Jim O’Neal

In the fifth century B.C., Herodotus noted in his “History” that every Babylonian was an amateur physician, since the sick were laid out in the street so that any passerby could offer advice for a cure. For the next 2,400 years, that was as good an approach as any to curing infections; doctors’ remedies were universally useless.

Until the middle of the 20th century, people routinely died from infections. Children were killed by scarlet fever, measles and even tonsillitis. Mothers systematically died from infections following childbirth and many who survived were taken later by pneumonia or meningitis.

Soldiers most commonly died from infections such as gangrene or septicemia, not from war injuries. Even a small cut could lead to a fatal infection. Bandaging a wound simply sealed in the infectious killers to carry out their deadly missions. Of the 10 million killed in World War I, 5 million died of infections.

There were few antidotes to infections … vaccination against smallpox with cowpox vaccine (Edward Jenner in 1796), introduction of antiseptics (Joseph Lister in 1865), and the advent of sulfa drugs in 1935. But there was no known cure for a stunning number of other deadly threats: typhoid fever, cholera, plague, typhus, scarlet fever, tuberculosis. The list seemed endless and most of these ended in death.

All of this changed in 1940.

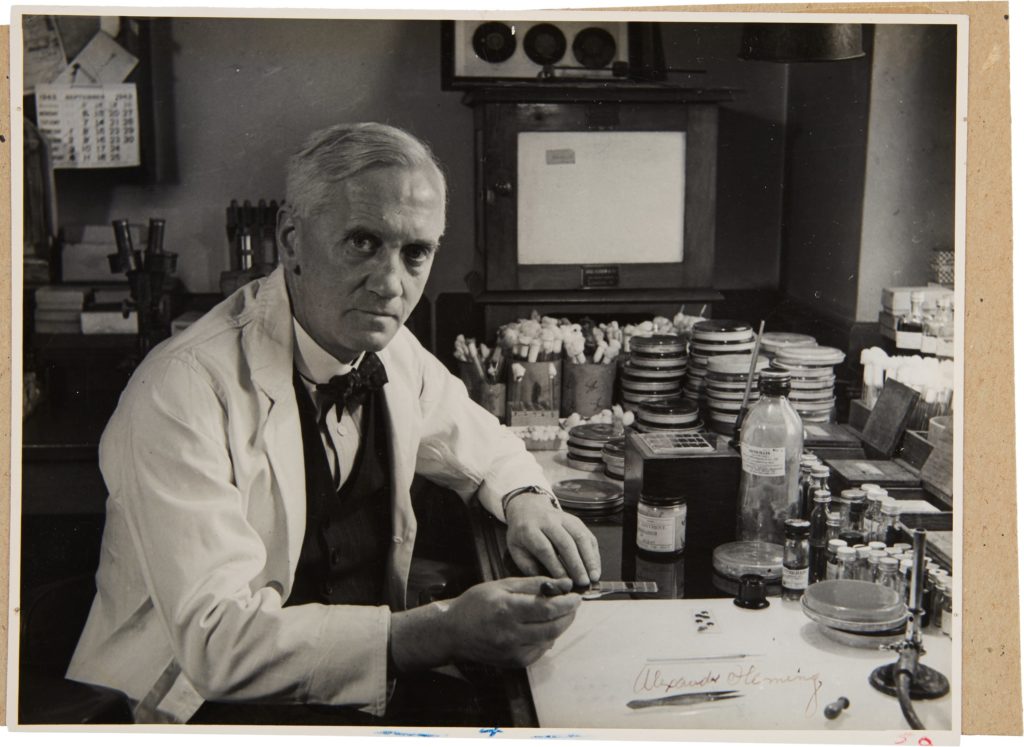

Alexander Fleming’s discovery of penicillin while examining a stray mold in his London lab in 1928, and its eventual development by a team at Oxford University, led to the discovery of antibiotics. This was the most important family of drugs in the modern era. Before World War II ended, penicillin had saved the lives of hundreds of thousands and offered a viable cure for major bacterial scourges such as pneumonia, blood poisoning, scarlet fever, diphtheria and syphilis/gonorrhea.

The credit usually goes to Fleming, but the team of Howard Florey, Ernst Chain, Norman Heatley and a handful of others on the Oxford team deserve a major share. The efficacy and eventual use of the drug required them to perform their laboratory magic.

Neither Fleming nor Florey made a cent from their achievements, although Florey, Fleming and Chain did share a Nobel Prize. British pharmaceutical companies remarkably failed to grasp the significance of the discovery, so American companies – Merck, Abbott, Pfizer – quickly grabbed all the patents and proceeded to make enormous profits from the royalties.

The development of antibiotics is one of the most successful stories in the history of medicine, but it is unclear whether its ending will be a completely happy one. Fleming prophetically warned in his 1945 Nobel lecture that the improper use of penicillin would lead to it becoming ineffective. The danger was not in taking too much, but in taking too little to kill the bacteria and “[educating] them on how to resist it in the future.” Penicillin and the antibiotics that followed were prescribed too freely for ailments they could cure, and for other viral infections they had no effect on. The result is strains of bacteria that are now unfazed by antibiotics.

Today, we face a relentless and deadly enemy that has demonstrated the ability to mutate at increasingly fast rates – and these “super bugs” are capable of developing resistance. We must be sure to “keep a few steps ahead.”

Hear any footsteps?

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is President and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as Chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is President and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as Chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].