By Jim O’Neal

March 4, 1893, marked the second time Stephen Grover Cleveland was inaugurated as president of the United States. He was greeted at the Executive Mansion by President Benjamin Harrison, the Republican he had defeated three months earlier. It was a mildly awkward meeting, the only time in history the transfer of presidential power involved outgoing and incoming presidents who had run against each other twice (each one winning once and losing once).

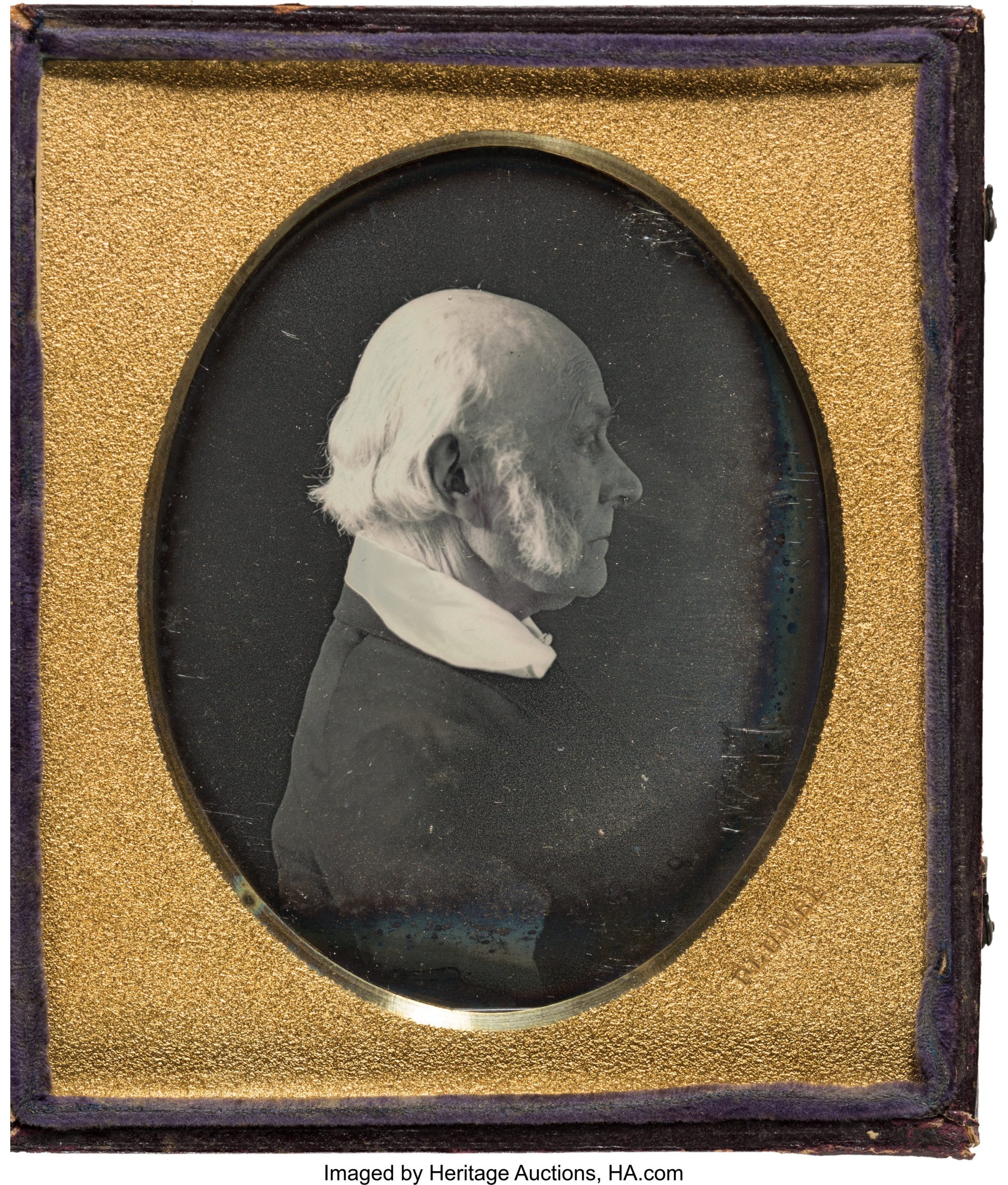

Benjamin “Little Ben” Harrison (he was 5-feet-6) was notoriously cold and aloof and President-elect Cleveland was stubbornly independent, with an aura of self-righteousness. Historian Henry Adams observed that “one of them had no friends and the other only enemies.” Robert G. Ingersoll, nicknamed “The Great Agnostic,” went a step further: “Each side would have been glad to defeat the other, if it could do so without electing its own candidate.” Strangely, I felt the same way in both 2016 and 2020.

Inauguration Day was bitterly cold and many recalled that Harrison’s grandfather, William Henry Harrison (the ninth president) had died 31 days after his inauguration. Following a very long acceptance speech, he caught pneumonia and it was fatal. He was 68 and at the time the oldest person to assume the presidency, a distinction he held until 1981 when Ronald Reagan was sworn in at age 69.

In 1893, President-elect Cleveland’s vice president, Adlai E. Stevenson, took the oath of office first. Sixty years later, his grandson (and namesake) would make two futile runs for the presidency (1952 and 1956). He had the bad luck of having one of America’s greatest heroes, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, as an opponent. War heroes are difficult to defeat and, in this case, it’s generally acknowledged that Ike could have beaten anyone and run on either party’s ticket. Outgoing President Harry Truman had even tried to broker such a deal in 1948 when he offered to step down to vice president.

Sadly, the 1892 election was vexed by Harrison’s wife contracting tuberculosis and dying two weeks before the election of Cleveland. But, after the inauguration and traditional transition, the ex-president seemed more than ready to return to his home in Indianapolis. Surprisingly, four years later, some of Harrison’s friends tried to convince him to seek the presidency again. He declined, but did agree to travel extensively making speeches in support of William McKinley’s successful candidacy. Little Ben died in February 1901 from pneumonia and a short six months later, President McKinley would become the third president to be assassinated.

But today belonged to President Cleveland and his wife Frances. They had been married during the first term in office on June 2, 1886, in the Blue Room at the White House. Cleveland was 49 years old at the time, Frances a mere 21. Frances Folsom Cleveland was the youngest First Lady in history and became very popular, primarily due to her youthful personality. They would have five children with the first one named Ruth. No, she was definitely not associated with Baby Ruth. That candy bar was renamed 30 years after her birth and 17 years after her death. After a warm welcome at the White House, President Cleveland’s troubles started almost right away.

In May, barely two months back in the White House, Cleveland discovered a growth on his palate, the soft tissue in the roof of the mouth that separates the oral and nasal cavities. It turned out to be a malignant tumor that required surgical removal. Fearful of panic in the already shaky financial markets, a clever plan was devised to perform a secret operation on a yacht in the East River. The surgery was successful and the president recuperated while sailing innocently on Long Island. The press was surprisingly gullible and accepted a story about two teeth that needed removal.

However, on dry land, economic forces were forming a dark storm that would usher in the worst financial crisis in the nation’s history. The pending depression would become known as the Panic of ’93. The 19th century had weathered many boom-bust economic cycles, but this powerful downturn would persist until the 20th century. Even as the president was organizing his cabinet, banks, factories and farms were tumbling into bankruptcy. Virtually everywhere, workers were struggling with layoffs and payouts as companies were swept away.

In his inaugural speech, Cleveland had warned about the dangers of business monopolies and inflation, however, his response to the economic chaos was austere in the extreme. He did not believe government should intervene for fear of eroding self-reliance and over-reliance on government. This was a common belief and it would take another generation for a new consensus to shape American politics. To fully grasp the significant schism that was silently evolving, one only has to read Thomas Sherman’s 1889 essay titled “The Owners of the United States.”

Using census data and promises of anonymity, he developed the thesis that 1/30th of the people in England owned 2/3 of the wealth. In America, he listed 70 individuals worth $2.7 billion and asserted no other country had such a concentration of millionaires. By contrast, 80% of Americans earned less than $500 annually, and 50,000 families owned half of the nation’s wealth. Further, wealthy men and corporations escaped taxation, with the burden falling “exclusively upon the working class.”

Memo to Elizabeth and Bernie: You’ve been scooped by roughly 130 years. Somehow, we managed to have a decent 20th century, save the world several times and develop a technological cornucopia for 330 million people vs. any other time in the history of the world. Go Bezos, Jobs/Allen, the Google guys, Walmart, Henry Ford, FDR and my man T.R.!

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].