By Jim O’Neal

One of the world’s greatest hucksters died in 1891. He was born in Bethel, Conn., and died 80 years later on April 7 in Bridgeport, where he had been mayor in 1875-76. Earlier, he had served four terms in the Connecticut House of Representatives, without distinction. The three-ring circus of modern life with all its hustle and bustle had to start somewhere, so why not simply start with the man responsible for the actual three-ring circus?

Phineas Taylor Barnum had been a loyal Democrat until the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act, which supported slavery, was drafted by Democrats and signed by President Franklin Pierce. It effectively nullified the 1859 Missouri Compromise, escalated tensions over the slavery issue and led to a series of violent civil confrontations known as “Bloody Kansas,” a political stain on American democracy.

Barnum promptly switched political parties, becoming a member of the new anti-slavery Republican Party, which was expanding rapidly with defecting abolitionists. John C. Frémont – “The Pathfinder” – was the first presidential candidate of the Republican Party, losing to Democrat James Buchanan in 1856. Abraham Lincoln prevailed in 1860 and 1864, and Republicans would dominate national politics for the rest of the 19th century.

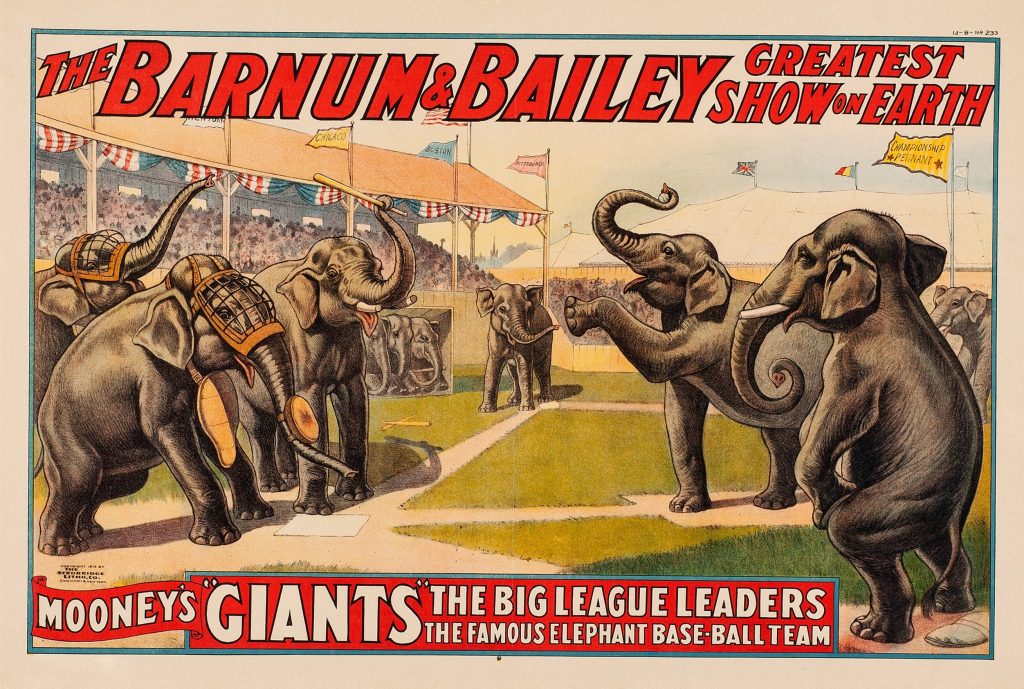

Yes, we’re talking about that Barnum, who would become world famous as founder of “P.T. Barnum’s Grand Traveling Museum, Menagerie, Caravan & Hippodrome.” Most Americans know the name, but whether they know that “P.T.” stands for Phineas Taylor or that he did not enter the circus business until he was 60 years old is doubtful. If not, then it is surely because of the extraordinary, eponymous circus formed when he and James Bailey teamed up in 1881.

Barnum was an energetic 70-year-old impresario. “The Greatest Show on Earth” may have been a slight exaggeration, but it’s not clear who would have rivaled them for the top spot. Clearly it was a distinctive assertion in a life filled with remarkable contradictions. Perhaps it is more precise to think of him as “the Greatest Showman on Earth” or other lofty positions as one desires. (He would undoubtedly find an angle to exploit to the fullest).

He actually had a modest beginning in his show-biz career, starting at age 25. He purchased a blind, nearly paralyzed black slave woman (Joice Heth) who purportedly was 161 years old and a nurse to a young George Washington. She sang hymns, told jokes and answered audience questions about “Little George.” Barnum cleverly worked around existing laws and exhibited her 10 to 12 hours a day to recoup his $1,000 investment.

As Barnum bribed newspaper editors for extra press coverage (always mentioning his name), he also co-produced a sensationalized biographical pamphlet to further hype the hoax. When Heth died in 1836, Barnum sold tickets to another “event” – a public autopsy to judge her actual age. More than 1,300 people eagerly attended the spectacle, which critics slammed as “morally specious.” At 50 cents a ticket, it provided a surprisingly nice profit. Barnum attempted to appease the abolitionists by claiming (falsely) that all proceeds from this flagrant exploitation would be used to buy her great-grandchildren’s freedom.

It is here that that experts who study such arcane issues will argue that it’s important to define the pejorative term “humbug,” using Barnum’s own precepts. To him, a humbug was a fake that delights audiences without scamming them. It is sleight of hand, not bait-and-switch. He called himself the “Prince of Humbugs.” Perhaps it is a distinction without a difference. However, Barnum, still searching for a code of ethics, fled this humbug. Even in his 1854 biography, he wrote that he wanted people to remember him for something other than Joice Heth. It would haunt him until his death.

By 1841, he was touring the country with magicians and jugglers. He bought John Scudder’s struggling American Museum in lower Manhattan, promptly renaming it with the Barnum brand. While displaying a cabinet of curiosities, he introduced pseudo-scientific exhibitions, live freaks and the normal hokums. Still struggling with his ethical bankruptcy, he gambled on backing a national tour for Jenny Lind, the most celebrated soprano in the world, offering her $1,500 for every performance. He calculated it would be worth losing $50,000 just to enhance his reputation.

Her virtuosic arias drew crowds in the thousands, as Barnum wishfully hoped his association with “the Swedish Nightingale” would lessen his reputational baggage. But driven by an outsize eagerness to enrich himself, he peddled spectacles like the “Feejee Mermaid,” the torso and head of a monkey and the back half of a fish, bound together by the clever art of taxidermy. He continued to worship at the altar of celebrity and the power of the press. He created attractions like General Tom Thumb, who at 5, learned to drink wine; at 7, he was smoking a cigar.

He parlayed an audience with President Lincoln into a European tour involving Queen Victoria, gambling that her subjects would be interested as well. The trip paid off big and was extended to include visits with the Tsar of Russia and other nobles. It is not surprising that in his quest for money and fame, his name itself conjured up qualities of audacity, greed and humbug. But how to account or judge the value of excitement, entertainment and gentle controversy? Even as Charles Darwin was jolting the scientific and religious communities with evolution via his Origin of Species, P.T. Barnum introduced William Henry Johnson, a microcephalic black man who spoke a mysterious language … “solving” the quest to find the Missing Link of mankind.

Sadly, on May 21, 2017, Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus gave the last performance of its 146-year history after the elephants had vanished under pressure from animal rights activists. The audience rose for a standing ovation while singing Auld Lang Syne. Then it was over.

Except that it wasn’t!

P.T. Barnum, famous for grabbing headlines, reached up from the grave as Hugh Jackman lionized him in the movie The Greatest Showman. Recent one-word-titled books like Fraud, Hoax and Bunk have found analogies to today while a generation of Madonnas, Warhols and Kardashians have mastered the media to enhance the power of celebrity. We now have the modern equivalent of a three-ring circus continuously playing on Twitter or any cable news channel 24/7. The Romans knew this when they built the coliseum and so did Walt Disney when Disneyland popped up in 1955.

I do miss the cotton candy.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].