By Jim O’Neal

In the 1880s, American physicist Albert Michelson embarked on a series of experiments that undermined a long-held belief in a luminiferous ether that was thought to permeate the universe and affect the speed of light ever so slightly. Embraced by Isaac Newton (and almost venerated by all others), the ether theory was considered an absolute certainty in 19th century physics in explaining how light traveled across the universe.

However, Michelson’s experiments (partially funded by Alexander Graham Bell) proved the exact opposite of the theory. In the words of author William Cropper, “It was probably the most famous negative result in the history of physics.” The fact was that the speed of light was the same in all directions and in every season – reversing Newton’s law that had been thought to be a constant for the past 200 years. But, not everyone agreed for a long time.

The more modern scientist Max Planck (1858-1947) helped explain the resistance to accept new facts in a rather novel way: “A scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it.”

Even if true, it still makes it no less easy to accept the fact that the United States was the only nation “that remained unconvinced of the merits of Joseph Lister’s methods of modern antiseptic medicine.” In fact, Henry Jacob Bigelow (1818-1890), the esteemed Harvard professor of surgery and a fellow of the Academy of Arts and Sciences, derided antisepsis as “medical hocus-pocus.” This is even more remarkable when one considers he was the leading surgeon in New England and his contributions to orthopedic and urologic surgery are legendary.

But this short story begins with a sleight of hand by asking: In the 19th century, what do you think was the most dangerous place in the vast territories of the British Empire? The frozen wastes of the Northwest Passage or the treacherous savannas of Zululand? Or perhaps the dangerous passes of Hindu Kush? The surprising answer is almost undoubtedly the Victorian teaching hospital, where patients entered with a trauma and exited to a cemetery after a deadly case of “hospital gangrene.”

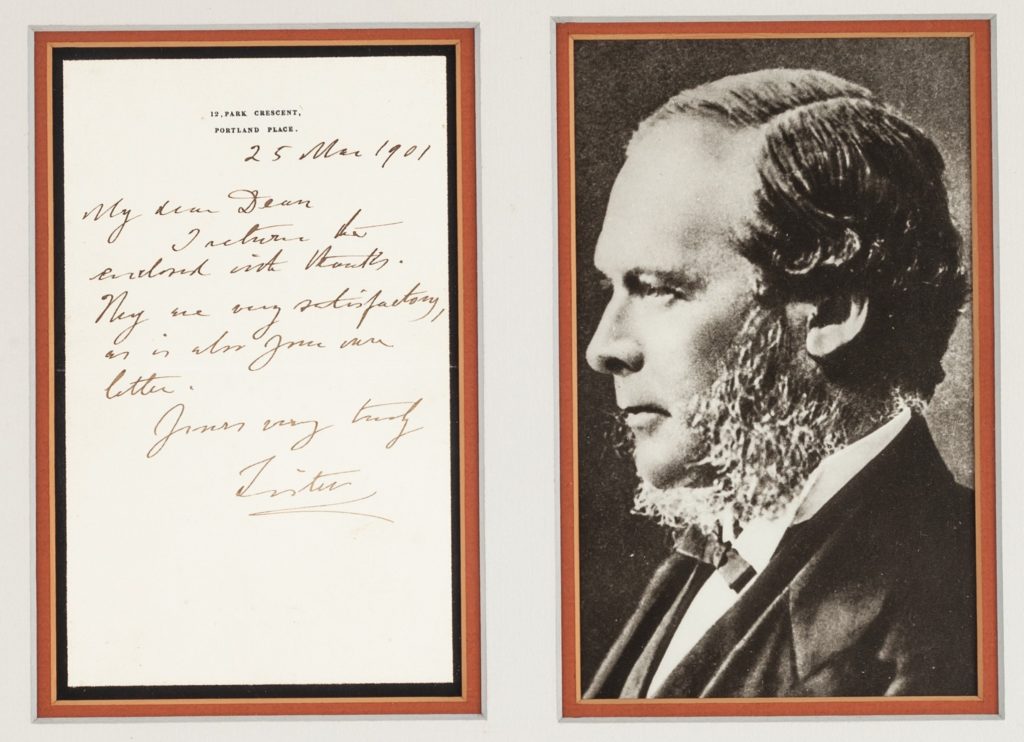

Victorian hospitals were described as factories of death, reeking with an unmistakable stench resembling rotting fish, cheerfully described as “hospital stink.” Infectious wounds were considered normal or beneficial to recovery. Stories abound of surgeons operating on a continuous flow of patients, and bloody smocks were badges of honor or evidence of their dedication to saving lives. The eminent surgeon Sir Frederick Treves (1853-1923) recalled, “There was one sponge to a ward. With this putrid article and a basin of once clear water, all the wounds in the ward were washed twice a day. By this ritual, any chance that a patient had of recovery was eliminated.”

Fortunately, Joseph Lister was born in 1827 and chose the lowly, mechanical profession of surgery over the more prestigious practice of internal medicine. In 1851, he was appointed one of four residents of surgery at London’s University College Hospital. The head of surgery was wrongfully convinced that infections came from miasma, a peculiar type of noxious air that emanated from the rot and decay.

Ever skeptical, Lister scoured out rotten tissue from gangrene wounds using mercury pernitrate on the healthy tissue. Thus began Lister’s lifelong journey to investigate the cause of infection and prevention through modern techniques. He spent the next 25 years in Scotland, becoming the Regius Professor of Surgery at the University of Glasgow. After Louis Pasteur confirmed germs caused infections rather than bad air, Lister discovered that carbolic acid (a derivative of coal tar) could prevent many amputations by cleaning the skin and wounds.

He then went on the road, advocating his gospel of antisepsis, which was eagerly adopted by the scientific Germans and some Scots, but plodding and practical English surgeons took much longer. Thus left were the isolated Americans who, like Dr. Bigelow, were too stubborn and unwilling to admit the obvious.

Planck was right all along. It would take a new generation, but we are the generation that has derived the greatest benefits from the astonishing advances in 20th century medical breakthroughs, which only seem to be accelerating. It is a good time to be alive.

So enjoy it!

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].