By Jim O’Neal

In May 1876, President Ulysses S. Grant and his wife Julia traveled to Philadelphia from Washington to open the Centennial Exposition in Fairmount Park. The United States was celebrating its 100th birthday and the signing of the Declaration of Independence. It was also a great opportunity to display the remarkable industrial progress that had occurred during the intervening years, especially in the 19th century. The exhibition was the result of three years of extensive planning and it was an impressive accumulation of American ingenuity.

On May 10, before an excited crowd of 186,672, Grant officially opened the fair following Wagner’s Centennial March. It was difficult to hear his speech due to crowd noise, but a flag raising and cannon volley was followed by a loud chorus of “hallelujah!” This was followed by a march to Machinery Hall, where a switch was thrown to spark the enormous Corliss electrical engine to power up all the machinery. At 50 feet tall, it was the largest in the world and powered more than 100 machines on display.

The First Lady was miffed that she wasn’t chosen to start the festivities and her pique exposed how accustomed she had grown to deference in the White House after eight years of pampering. But that honor went to Empress Teresa Cristina, wife of Emperor Dom Pedro II, the last emperor of the Brazilian empire. He had become emperor at age 5 when his father died and he reigned for an astounding 58 years (1831-1889).

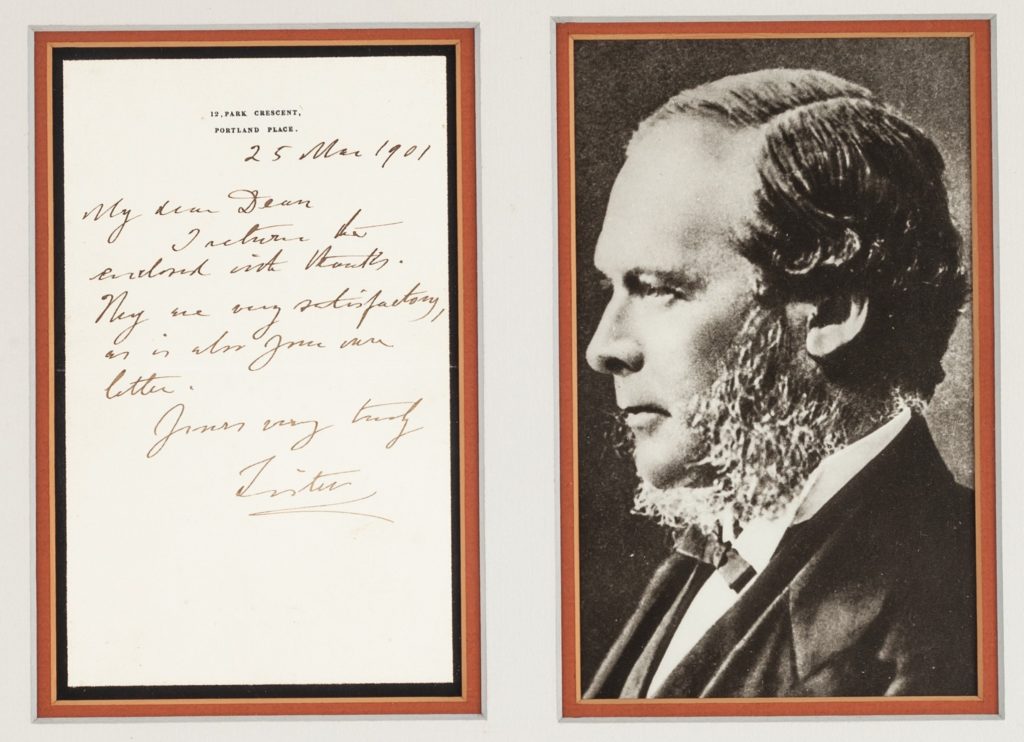

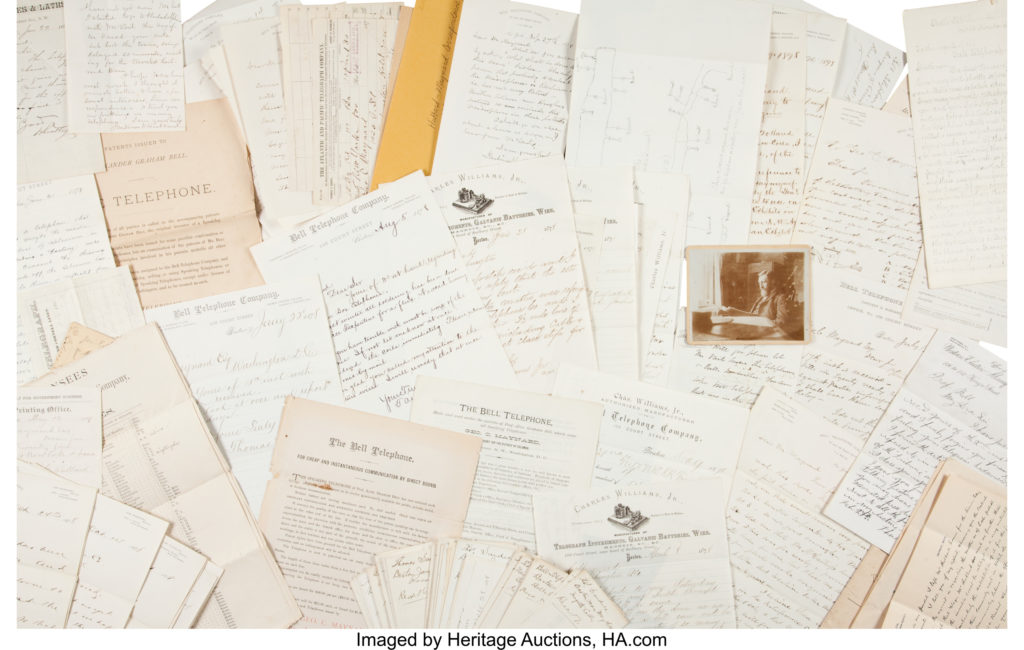

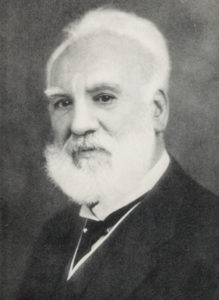

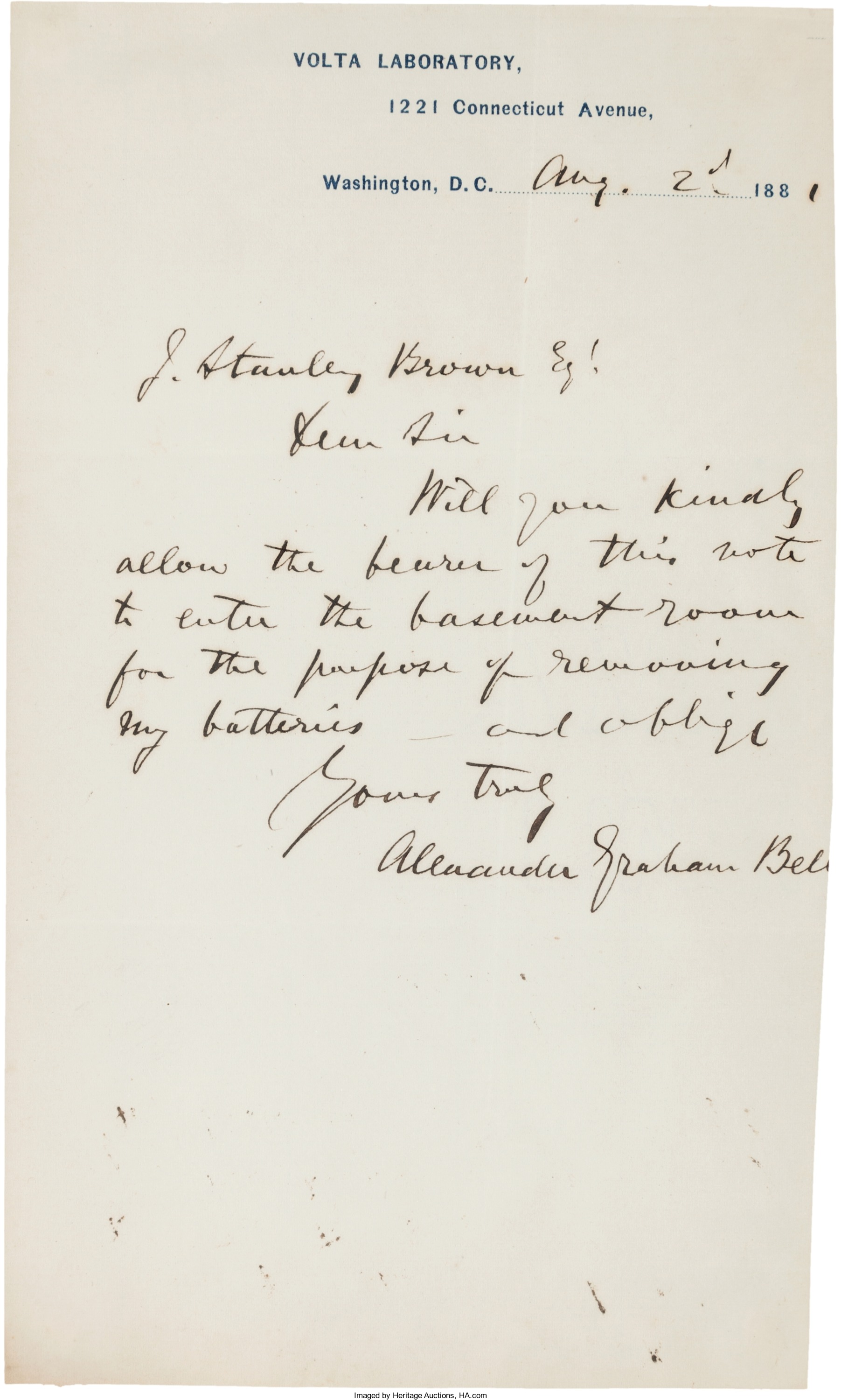

Dom Pedro had visited the United States earlier and had attended one of Alexander Graham Bell’s deaf-mute classes at Boston College. Inspired by Bell’s work, he founded the first deaf-mute school in Rio de Janeiro when he returned home. Coincidently, Bell had been persuaded to exhibit his latest invention at the fair: the Bell telephone. When the affable emperor learned of Bell’s exhibit, he eagerly agreed to try the device in a demonstration for a crowd.

Placing the receiver to his ear, he was treated to Bell’s personal recitation of Hamlet’s “To be or not to be” soliloquy. Delighted and astonished, Dom Pedro exclaimed, “My God, it talks!”

However, the general public proved to be less impressed and hard to sell. As one detractor complained, “It is a scientific toy … for professors of electricity and acoustics.” After convincing his father-in-law, lawyer and financier Gardiner Hubbard, Bell and his assistant Tom Watson set out on a demonstration tour. AGB would sit on a stage, connected to Watson via leased telegraph lines several miles away. After introductory remarks, Watson would sing a repertoire of tunes, including Yankee Doodle.

As an aside, AGB’s first coherent telephone message – “Mr. Watson, come here, I want to see you” – was really a plea for help. He had spilled battery acid on his pants and, instinctively, made the first emergency call in history. We know how that story progressed since we all carry around smartphones that have more computing power (and other functionality) than Apollo 11 when it made its historic manned flight to the moon in 1969.

Although Grant was cheered at the opening of the Centennial Exposition, any thoughts he had about a third term disappeared in a toxic haze of a weak economy and widespread corruption. When the Republican Convention met in Cincinnati in June, the party platform directly criticized Grant, calling the administration “a corrupt centralism … carpetbag tyranny … honeycomb federal government … with incapacity, waste and fraud.” Out of this cesspool stepped the governor of Ohio, Rutherford B. Hayes, an honest, sincere man with a commitment to limiting the presidency to a single term. Democrats picked the governor of New York, Samuel Tilden, with strong credentials having conquered Tammany Hall and the corrupt Boss Tweed ring of rogues.

Hayes won in 1876 after the most controversial presidential election in U.S. history. Grant was actually worried about a coup as Democrats, convinced the election was rigged, rallied under the cry of “Blood or Tilden.” Since March 4, 1877, was a Sunday, there was precedent to avoid having the inauguration on the Sabbath by waiting until the next day, as Presidents Monroe and Taylor had done. Grant was so paranoid about waiting an extra day that he arranged for a private ceremony on Saturday night as part of a routine dinner at the White House. Hayes was sworn in by Chief Justice Morrison Waite before the food was served.

On Monday, March 5, the ceremony was recreated (for show only) before a crowd estimated at 30,000. A teary-eyed Julia Grant was not one of them. She stayed in the White House as long as possible and I suspect she would have welcomed having another four years. She even hosted a luncheon for her successor after the inauguration. She later wrote, “How pretty the house was … in an abandon of grief, I flung myself on the lounge and wept, wept oh so bitterly.”

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].