By Jim O’Neal

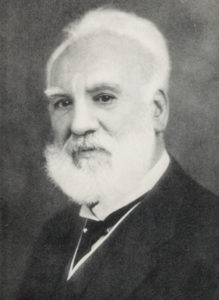

In 2013, Nancy and I took a cruise from New York City to Montreal. On Sept. 23, we had the great pleasure of touring the Alexander Graham Bell museum in Baddeck, Nova Scotia. We were struck by its unusual design, which is based on the tetrahedron form used in his many flight experiments with kites. There were also numerous original artifacts, photographs and exhibits of his groundbreaking scientific accomplishments.

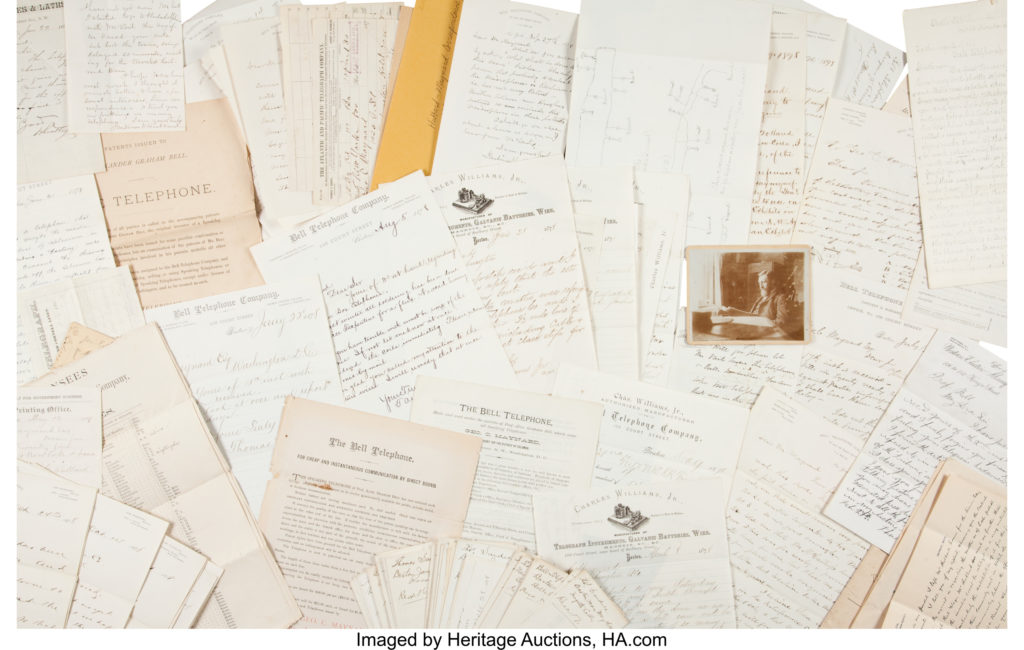

Bell (1847-1922) was awarded patent #174465 just four days after his 29th birthday for the first practical telephone – “the most valuable single patent ever issued” in any country. Our guide informed us that Bell would not allow a telephone in his study or laboratory since he considered it a distraction to his reading and experiments. I was aware that both his mother and wife were deaf and this had a profound effect on his passion for working on sound, speech and hearing. What surprised me was the breadth of his scientific achievements. He was awarded 18 patents and collaborated on another 12 in medicine, aeronautics, genetics, electricity, sound and marine engineering.

Another surprise was that his wife Mabel was the daughter of Gardiner Greene Hubbard, founder and first president of the National Geographic Society (founded in 1888) and also the first president of Bell Telephone Company (later AT&T). Although AGB (he got a middle name only after constantly nagging his father) was not a founder of National Geographic, he was its second president, following his father-in-law. This was organizational incest on a scale that rivaled the British monarchy.

But the result was an organization that has given several generations a certain sense of where we are and where we want to go. Commanders-in-chief, explorers, schoolchildren and even daydreamers have put their full trust in the splendid maps of the National Geographic Society and their brilliant cartographers. The elegant and clearly legible typefaces for place names, one source of the map’s mystique, were designed by the magazine’s staff in the 1930s.

It was founded in Washington, D.C., at the Cosmos Club, another venerable organization founded in 1878 and boasting of membership by three presidents, two vice presidents, 12 Supreme Court justices, and 36 Nobel and 61 Pulitzer Prize winners (they don’t bother with ordinary U.S. senators).

During World War II, National Geographic maps were at the epicenter of the action, thanks in part to a U.S. president who was deeply interested in geography. The society had furnished Franklin D. Roosevelt with a cabinet that was mounted on the wall behind the desk in his private White House study. Maps of continents and oceans could be pulled down by the president like window shades; they were in constant use throughout the war.

In the early winter of 1942, President Roosevelt urged the American people to have a world map available for his next fireside chat, scheduled for the evening of Feb. 23. FDR told his aides, “I’m going to speak about strange places that many have never heard of – places that are now the battleground for civilization. … I want to explain to the people something about geography – what our problem is and what the overall strategy of the war has to be. I want to tell it to them in simple terms of ABC so that they will understand what is going on and how each battle fits into the picture. … If they understand the problem and what we are driving at, I am sure that they can take any kind of news on the chin.”

There was an unprecedented run on maps and atlases. The audience, more than 80 percent of the country’s adult population, was the largest for any geography lesson in history.

The National Geographic Society went on, expanding the scope of its focus – with maps for the amazing Mount Everest to outer space and the ocean floor. As the Society’s former chief cartographer put it: “I like to think that National Geographic maps are the crown jewels of the mapping world.”

He was right, until Google maps created a new technology in need of its own headware.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].