By Jim O’Neal

One fact that is difficult to verify is the total net worth of the Rockefeller family fortune. John Davison Rockefeller Sr. (1839-1937) rose from pious beginnings to become the world’s richest man by creating America’s most powerful monopoly, Standard Oil Company. Scores of muckrakers (especially Ida Tarbell) scorned it as “The Octopus” and posters protested the company by showing it swallowing the world … whole.

He is definitely the most prominent and controversial businessman in our history, especially when the trust he created came from refining 90 percent of the oil produced and marketed in America. His vocal critics charged he was an unscrupulous man who colluded with railroads to fix prices, and conducted illegal industrial espionage and outright bribery of political officials. It took Teddy Roosevelt and his team of stalwart trustbusters to break the trust, but even that inured to his benefit since he had ownership shares in all the new, smaller entities that were created.

Although the business practices were as ruthless and corrupt as charged, he was a quirky, passionate, temperate advocate who was generous and gave enormous sums to organizations like the Rockefeller Foundation, University of Chicago and what is now Rockefeller University. As an old man (he lived to be 98), he was parodied as a harmless billionaire who delighted in giving shiny dimes to needy children.

The actual story has grown much more complex after his only son, John D. Rockefeller Jr. (1874-1960), took over the massive estate and had five sons of his own. The last one, David Rockefeller, died last year and his personal estate was auctioned off this month by an East Coast firm. The total net proceeds were consigned to 12 of his favorite charities, which will create another layer of veneer over the money. What we know is that 1,500 items sold for over $832 million, setting 22 records in the process.

Another son of Junior was Nelson Rockefeller (1908-1979), who was governor of New York and made unsuccessful attempts to snag the GOP presidential nomination in 1960, 1964 and 1968. After serving in other high-profile positions, he was chosen by Gerald Ford to be the 47th vice president of the United States after Richard Nixon’s resignation. Rockefeller holds the distinction of being the last VP to decline to seek re-election when he decided not to join the 1976 Republican ticket with Ford.

Andrew Carnegie (1835-1919) was another famous philanthropist who made a fortune in steel and spent the last 18 years of his life giving $350 million to charities, foundations and universities. “I should consider it a disgrace to die a rich man.” Both the Rockefeller and Carnegie names have been well known throughout the 20th century, primarily because of the numerous foundations and buildings that bear their names.

But let’s focus now on an equally generous man who is largely forgotten because no foundations and few buildings mention him.

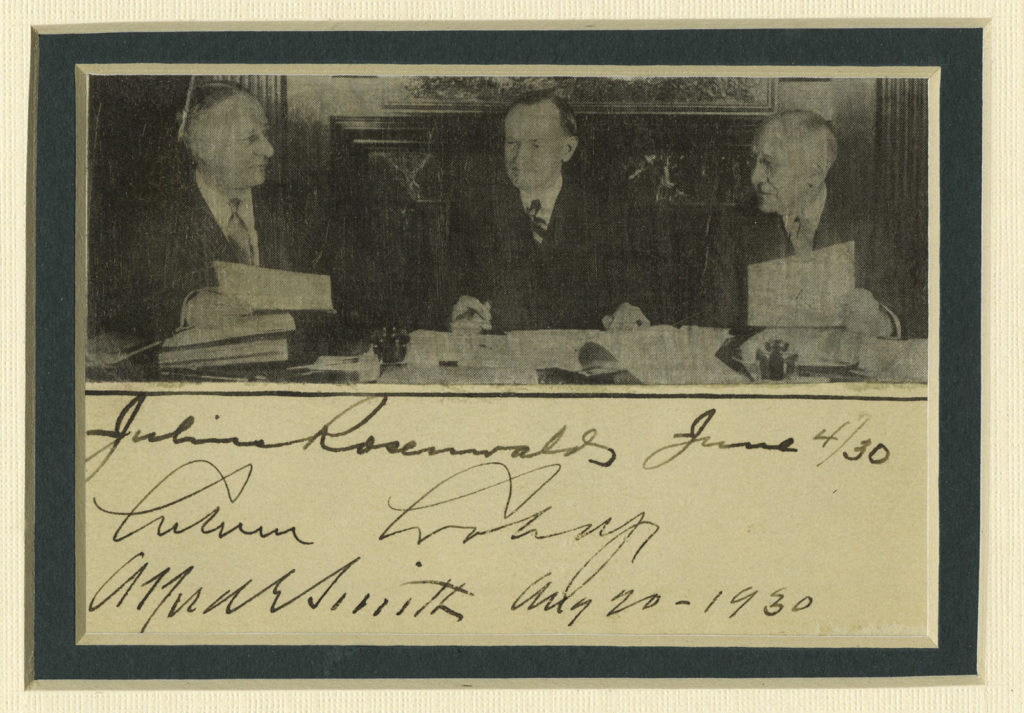

Julius Rosenwald (1862-1932) made his fortune the old-fashioned way. He earned it. He started running a clothing store in Springfield, Ill., and then went to New York to learn about the garment business. When he returned to Chicago, he opened another modest clothing store, but also started shrewdly investing in a small catalog store with the undistinguished name of Sears, Roebuck & Company. When co-founder Richard Sears left the company in 1908, Rosenwald assumed a leadership role. With financial help from Henry Goldman (son of Marcus Goldman of Goldman Sachs), he expanded the company with a massive 40-acre mail-order plant on Chicago’s West Side.

Then, in an unprecedented move in 1906, an IPO with Goldman was created, and Sears became a public company. Rosenwald had climbed from a vice president to chairman and CEO, and the new plant in Chicago, with a staggering 3 million square feet, became the largest building in the world. In the process, Sears became America’s largest retailer and people all over the United States discovered how to order using the mail, after hours of thumbing through the sacred Sears catalog.

The demise of Sears is well known and the company is currently being dismantled and sold by brand. It may not be as quickly forgotten as Julius Rosenwald, who went to extremes to be modest. When he died in 1932, it is estimated that he had donated $2 billion to a wide range of interests, including projects that funded African-American education in the South. He funded a program to construct elementary and secondary schools in any willing black community. Over a 20-year period, 5,000 schools were constructed in the South, 90 percent of all buildings in which Mississippi’s black youngsters received an education.

Not bad for a generous man who had no need for recognition, just a desire to help needy people. Now another generation of people will know what he did, in such a humble and modest way, by insisting on closing his foundation after his death and opposing the attachment of his name to so many projects.

Bravo.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].