By Jim O’Neal

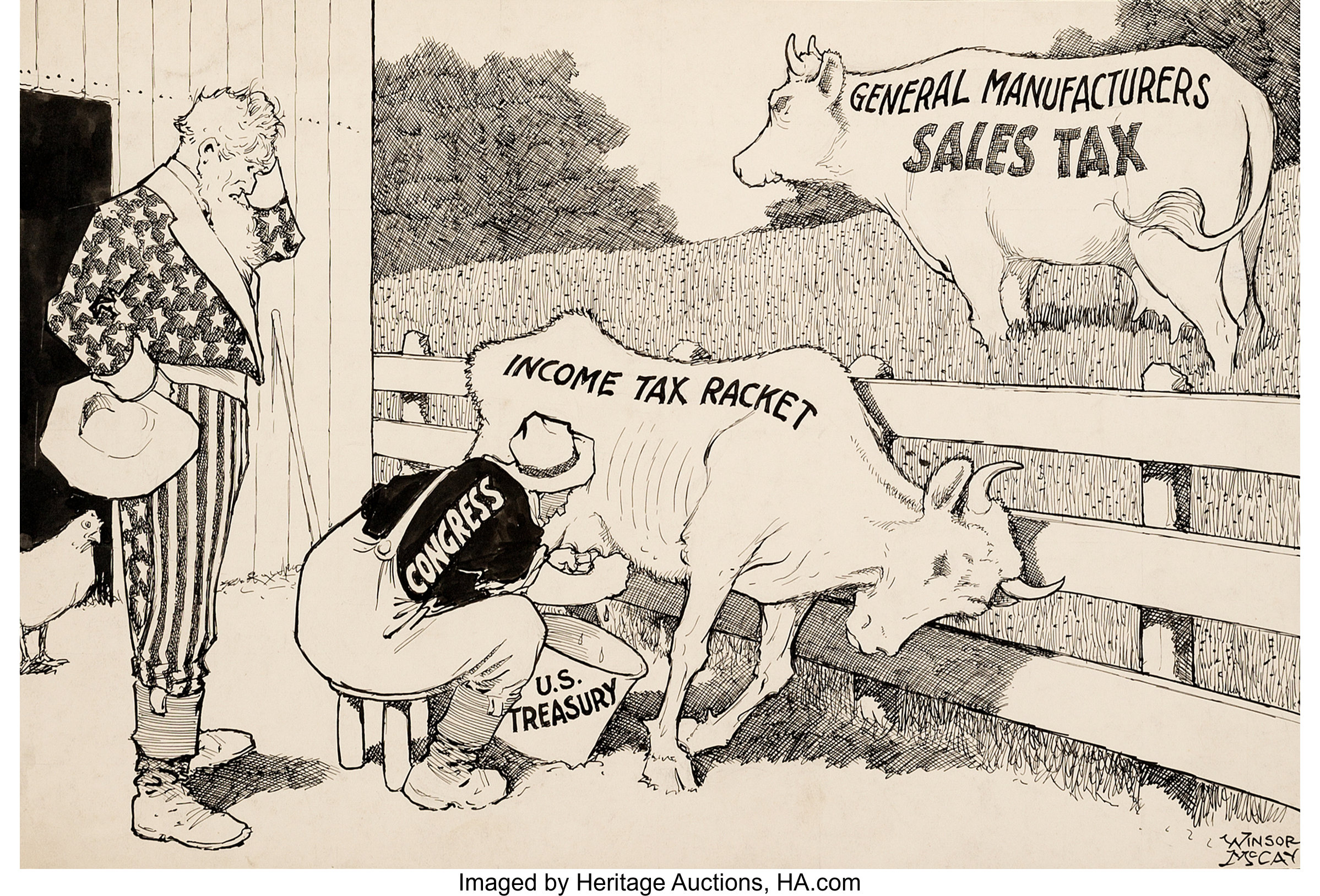

U.S. Rep. Schuyler Colfax of Indiana described the issue this way: “The most odious tax we can levy is going to be a tax on land. I cannot go home and tell my constituents that I voted for a bill that would allow a man, a millionaire, who has put his entire property into stock, to be exempt from taxation, while a farmer who lives by his side must pay a tax!” Colfax (1823-1885), who would later become one of only two men (with John Nance Garner) to be both speaker of the house and vice president, had a different proposal: Put a tax on stocks, bonds, mortgages and interest. A de facto income tax.

There was ample precedent for an income tax. England imposed one in 1799 and various states – which relied primarily on estate taxes – had begun taxing income in the 1840s. By 1850, some states had income taxes with high exemptions and low rates that graduated based on the wealth of the taxpayer. They didn’t raise much revenue, but were viewed as a way of taxing any wealth that escaped common real estate taxes. Colfax prevailed and the Ways and Means Committee dropped the property tax and replaced it with “direct taxation upon personal income or wealth.”

The only issues remaining were the constitutional restrictions on direct taxes, except in proportion to population (i.e. different tax rates for different states). The solution was simple. Call the new taxes something other than a direct tax and “impose the burden on the people equally in proportion to their ability to pay.” An amendment was adopted to impose a 3 percent tax on income over $600 a year and a luxury tax on alcohol and luxury goods.

The Senate went one step further with a 5 percent tax on income over $1,000. Eventually, they compromised on 3 percent for income over $800. At last, said The New York Herald, millionaires would contribute a fair proportion of their wealth to the support of the national government. Inequality would soon be a relic of the past and every man would pay according to his ability!

The time was early 1862 and Secretary of the Treasury Salmon Portland Chase realized he had grossly underestimated the cost of the Civil War. After the embarrassment at Bull Run and a reassessment of Gen. George McClellan’s preference to train his troops rather than engage the South in battle, a new estimate of the first year’s cost was a staggering $530 million. Chase doubted that merely labeling the new income tax an “indirect tax” was constitutional. More importantly, Congress had neglected to establish any means for collecting or enforcement of the new tax. The decision was made to view the tax legislation as simply a recommendation and everyone conveniently ignored it.

However, this left the Treasury with an urgent need to start borrowing money to fund the war effort and the challenge was growing more daunting each day. Treasury funds were facing a virtual depletion in a matter of weeks and American banks were adamant that the Union raise taxes rather than expect more loans. Without new revenues, the Union was in peril and the urgency was significant. President Lincoln found it convenient to cede authority to Chase and plead ignorance whenever the issue of finance was raised.

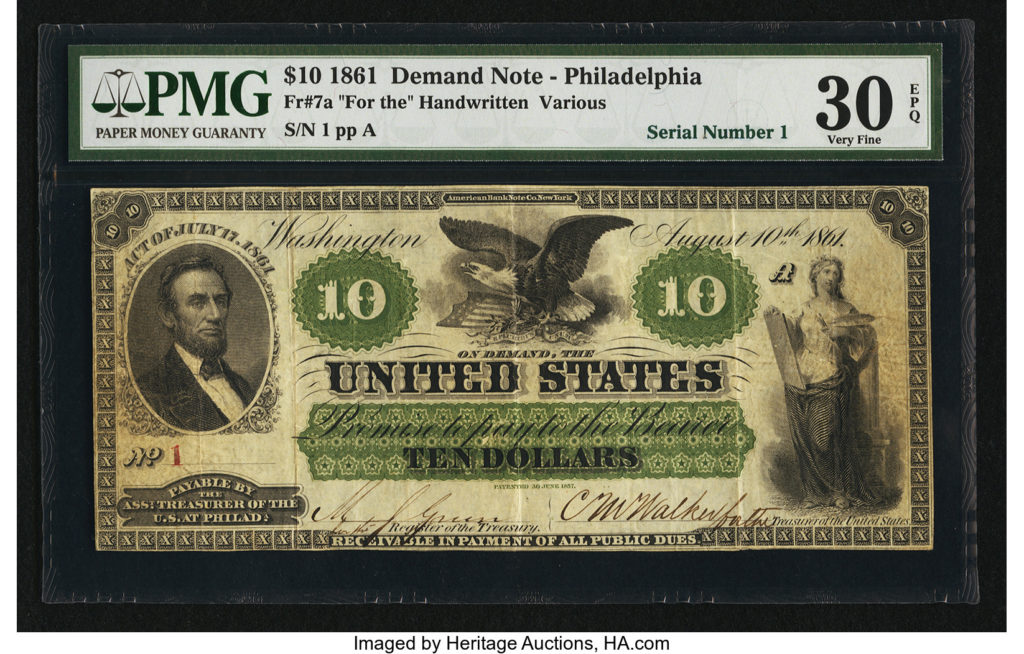

An earlier gambit in late 1861 to raise $150 million through a consortium of banks had failed when debt instruments were only partially subscribed to and government gold supplies were totally inadequate to cover the mounting financial needs. Trapped without any viable traditional options, Lincoln and Chase broke with longstanding traditions and accepted the idea to simply print the money needed. Congress passed the Legal Tender Act of 1862, turned on the printing presses and cranked out $150 million that the government declared as legal tender for private and public debts. An important proviso of the new “green backs” was that they were not redeemable for gold or silver and not for payment of customs duty or federal bonds and notes.

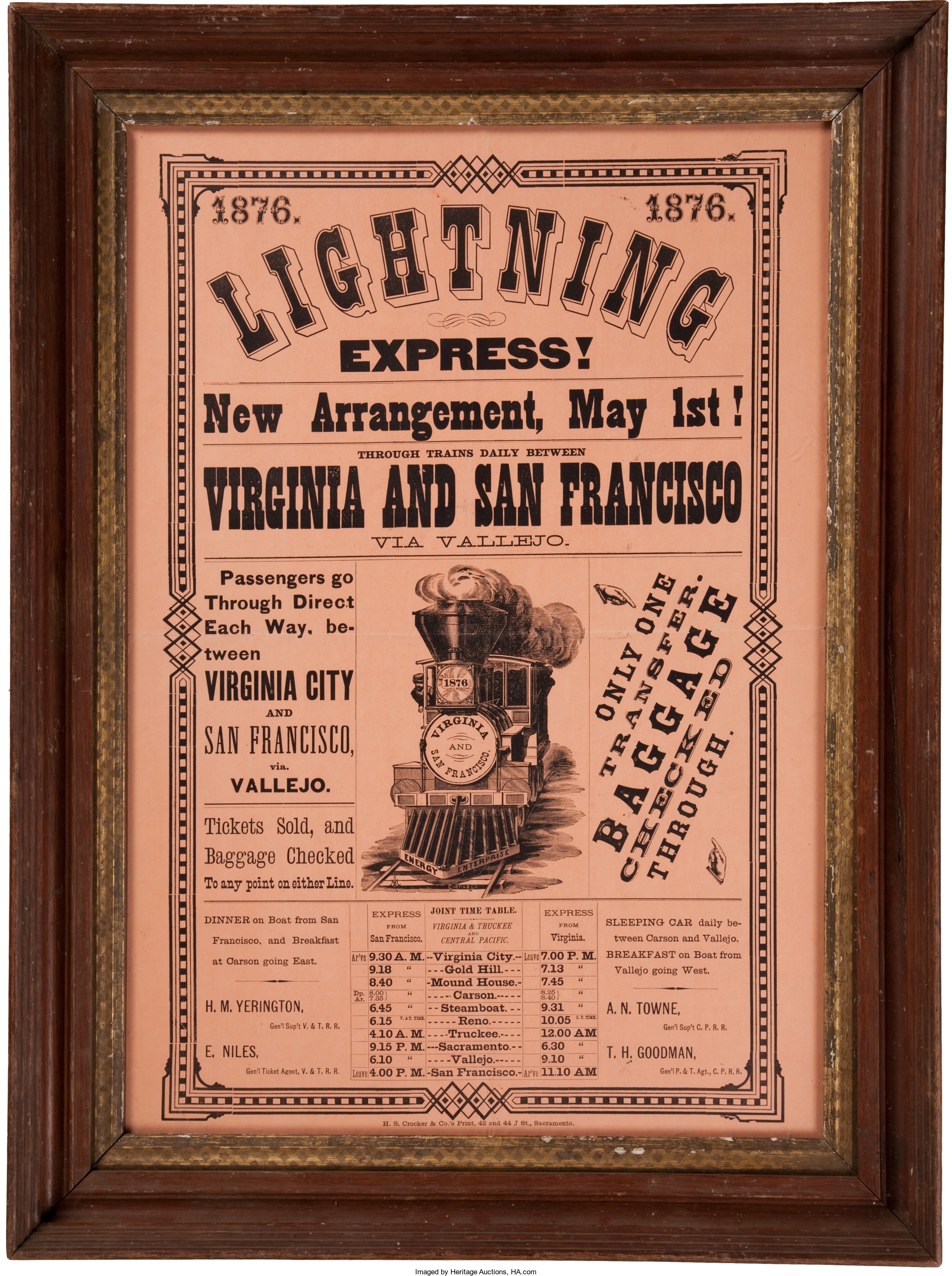

Most estimates for the cost of the war (1861-65) range from $6.2 billion for the Union and at least $2 billion for the South. These little wars can become very expensive if allowed to continue … a lesson we have learned once again in the Middle East (estimated at $80 billion “tops” … to actual $3 trillion and growing). But if you own a printing press, no problem.

In 1894, Congress tried to introduce an income tax of 2 percent on earnings over $4,000, but the Supreme Court ruled it unconstitutional. Income tax would not become a regular part of everyday life until 1914. However, once it did, the battles over taxes versus government spending (and who should pay) has become de rigueur.

“Don’t tax you. Don’t tax me. Tax that guy behind the tree.”

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].