By Jim O’Neal

On April 25, 1898, the U.S. Congress declared war on Spain, ostensibly because of the sinking of the battleship USS Maine on Feb. 15. The armored cruiser was docked in Cuba’s Havana Harbor, having been dispatched by President McKinley to protect America’s people and interests during an uprising of Cuban dissidents. The cause of the explosion is still a subject of debate yet today.

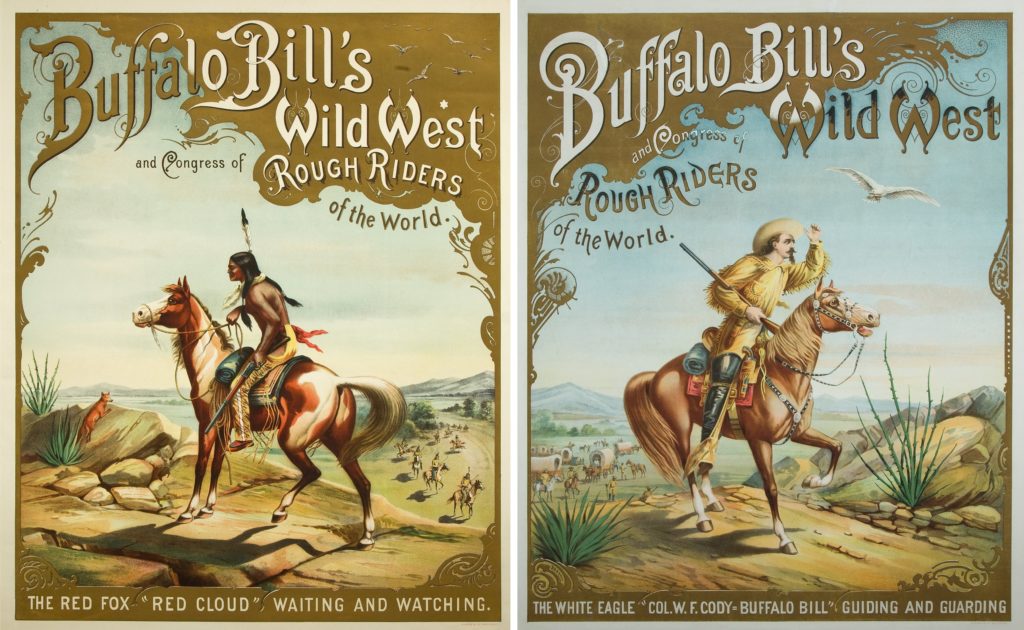

The first act of war was to prevent Spain’s battleships in the Philippines from going to Cuba to join in the pending fighting. When the U.S. Army arrived in Cuba, they won a series of battles. The most famous was San Juan Hill, featuring a group called the Rough Riders. They were primarily farmers and cowboys that comprised the 1st U.S. Volunteer Cavalry that also included future President Theodore Roosevelt. TR was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor in 2001 for his actions in Cuba.

It was a short war (the actual fighting stopped by Aug. 13) and a formal treaty was signed on Dec. 10. Cuba gained its long quest for independence and the United States gained control of Guam, Puerto Rico and the Philippines islands, an archipelago south of China. American business interests viewed the Spanish colony as a strategic gateway to lucrative trade with East Asian markets.

However, these islands had been under Spanish control since 1521 and Filipinos had also been waging a war of independence since 1896. Gaining their support to oust Spain was critical. U.S. Navy forces were under the command of Commodore George Dewey, and the Battle of Manila Bay against the Spanish flotilla started early on May 1, 1898. Spanish battleships and harbor fort guns were out of range to reach the American fleet, but Admiral Dewey had superiority in armaments. After confirming the distance, he gave a famous command to the captain of the USS Olympia: “You may fire when you are ready, Gridley.” What followed was the destruction of eight Spanish battleships and with only seven American seamen wounded. The entire battle was over in the first day of fighting.

Spain surrendered and sold the Philippines to the United States for $20 million.

Perhaps, not surprisingly, Filipino nationalists were not interested in trading one colonial master for another. In February 1899, fighting between Filipinos and the U.S. military started. In June, the Filipino Republic officially declared war on the invading U.S. forces. Suddenly, the United States had become mired in a war of colonial conquest. It would last for three years and become exceedingly vicious at times.

The United States controlled the capital of Manila, but Filipino revolutionaries, outgunned but with the advantage in manpower and home terrain, predictably resorted to guerilla warfare. U.S. forces quickly forced civilians into internment camps to prevent them from helping or joining the guerillas. It took until 1903 for the United States to prevail, with American troops suffering more than 4,000 casualties, 75 percent from tropical diseases. Roughly a quarter-million Filipinos perished, 90 percent of them innocent civilians. It was not until 1946 that the Treaty of Manila granted the Philippines full independence.

Looking back to the early 19th century, Spain’s colonies in North America were vastly superior to the young United States. This situation was totally reversed by 1900. In terms of territory, population and resources, the United States dominated the Western Hemisphere. It is a story of Protestant austerity, democracy and incursions led by American frontiersmen, farmers, shopkeepers, bankers and waves of European immigrants arriving on our shores, ready to make their fortunes.

The Spanish colonies fragmented as the primarily Catholic and tyrannical governments were unable to maintain coherence and viability. The transformation is marked by three distinct phases starting with Florida and the Southeast by 1820. This was followed by Texas, California, the greater Southwest (1855) and finally Central America and the Caribbean directly as a result of the Spanish-American War. During these major annexation phases, Mexico lost half its territory and 75 percent of its mineral resources.

The story of how to achieve Manifest Destiny from “Sea to shining sea” is embedded in these short episodes.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].