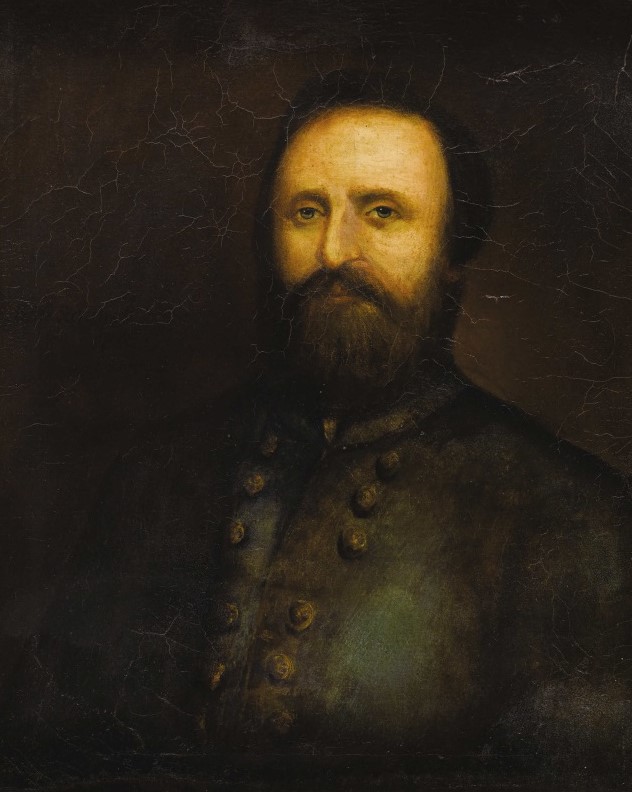

“Look! There is Jackson standing like a stone wall! Let us determine to die here today and we will conquer.” – General Barnard Bee, 1861, First Manassas/First Battle of Bull Run

By Jim O’Neal

Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson (1824-1863) was born at Clarksburg, deep in the mountains of what is now West Virginia. He was only 2 years old when his sister and father died of typhoid fever. The Jacksons had been longtime residents, but his father was a lawyer struggling with growing debt. His mother and three children were forced to become wards of the small town. Even after she remarried, they were unable to support the family and the children were sent individually to various relatives. Jackson’s mother died barely a year after the family break-up.

TJT grew up working for an uncle who ran a lumber and grist mill. The absence of parents or a real family resulted in a hardy young man, withdrawn and shyly introspective. He relied on friendly tutors and a love of reading to attain a very limited education. His first bit of luck occurred when a nominee for the U.S. Military Academy changed his mind and Jackson took his place.

Few, if any cadets ever entered West Point with less scholastic preparation. Moreover, the mountain lad was naturally introverted and almost entirely devoid of basic social skills. Somehow, he used energy, determination and a passion for learning in lieu of formal preparation. Studying day and night helped him rise from near the bottom to graduate 17th out of 59 cadets in the class of 1846.

The War with Mexico had just started and Jackson entered the Army as a lieutenant in the 3rd U.S. Artillery and he was dispatched at once to Mexico. After a slow start, he participated in the Siege of Veracruz in March 1847. Then he was cited for gallantry at both Contreras and Chapultepec. By the end of the war, he was a brevet major and had outperformed all of his West Point classmates.

After the war, he returned with the Army, first to New York and then to Fort Meade, deep in the middle of Florida. It was here that he received an offer from the small Virginia Military Institute (VMI) to be Professor of Artillery Tactics and Optics in Lexington, Va. He was plagued with health issues to the point that many historians believe he was a hypochondriac. That aside, he became intensely interested in religion, which would play a major role in his personal and military activities. Eventually, he joined the Presbyterian church and was a highly devout Calvinist.

The signs of the coming civil war were growing rapidly and as early as Oct. 16, 1859, John Brown made an effort at Harpers Ferry to initiate a slave revolt in Southern states by taking over the arsenal and arming slaves. Brown had 22 followers, but 88 Marines led by Colonel Robert E. Lee quelled the revolt. Stonewall Jackson was one of the troops guarding Brown until he was executed. By coincidence, John Wilkes Booth was one of the spectators at the hanging. Many refer to this incident as the “dress rehearsal for the Civil War.”

Stonewall Jackson remained a strong Unionist until he thought his beloved Virginia was threatened by federal coercion. When secession finally occurred, he offered his services to the Confederation. He left Lexington on April 21, 1861, never to see his adopted town again. Robert E. Lee, of course, was offered command of all Union forces, but like Jackson, his loyalty to Virginia was stronger than to the United States.

It was from here that Stonewall Jackson earned his reputation as one of the most brilliant commanders in American history. Even though his field services in the Civil War lasted but two years, his movements continue to be studied at every major military academy in the world. He was an artillerist who excelled in infantry tactics. He was a devout Christian but merciless in battle … paradoxical because of odd eccentricities, but an inflexible sense of duty, mixed with steel-cold tactics. One explanation offered was his belief that he was fighting on the order of Joshua, Gideon and other commanders of Old Testament fame. His credo was best summed up in a single statement: “My religious belief teaches me to feel as safe in battle as in bed. God has fixed the time for my death. I do not concern myself about that.”

Appointed a colonel of infantry on April 27, 1861, Jackson’s first orders were to return to the Shenandoah Valley and take command of an inexperienced militia and volunteers. This was a traumatic shock as the new commander assumed his duties with a stern regime. Units accustomed to parades underwent hours of daily drills, incompetents were quickly expunged and the town’s entire liquor supply was eliminated. The area was quickly ringed by armed pickets and artillery emplacements. Jackson taught the ignorant and punished the insubordinate.

It was such a rapid and dramatic transformation that Jackson was promoted to brigadier general on June 17 and given a brigade of five infantry regiments. The most famous nickname in American history came to Jackson just four weeks later at Manassas. His career proceeded at a dizzying pace and on Oct. 10, 1862, Jackson was appointed lieutenant general of half of General Lee’s forces. In spring 1863, Jackson performed his most spectacular flanking in the tangle of the Virginia Wilderness. He routed General Joe Hooker’s Army and for the first time rode to the front lines to personally assess the situation. He was returning when Confederates mistook the general and opened fire.

On May 2, three bullets struck Jackson, shattering his left arm below the shoulder. He died eight days later when pneumonia overtook him on May 10, 1863. His last words were “Let us cross over the river and rest under the shade of the trees.” The South had lost the most famous martyr of the Confederacy. General Robert E. Lee had lost the equivalent of his right arm. He never recovered.

For many years after the war’s end, Lee would speak of General Jackson. The words would vary, but the sentiment remained the same. “If I had Stonewall Jackson with me, I should have won the Battle of Gettysburg.” He even imagined Stonewall beside him in later battles, facing Grant in the Wilderness. “If Jackson had been alive and there, he would have crushed the enemy!”

For General Lee and for Americans ever since, the untimely death of Stonewall Jackson is the great “what if” of Civil War history. Jackson shaped the war in the Eastern theater with his aggressive tactics. His absence not only changed Confederate operations and Southern morale, but the tactical methods of General Lee.

“I know not how to replace him,” Robert E. Lee said at Stonewall Jackson’s funeral.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].