By Jim O’Neal

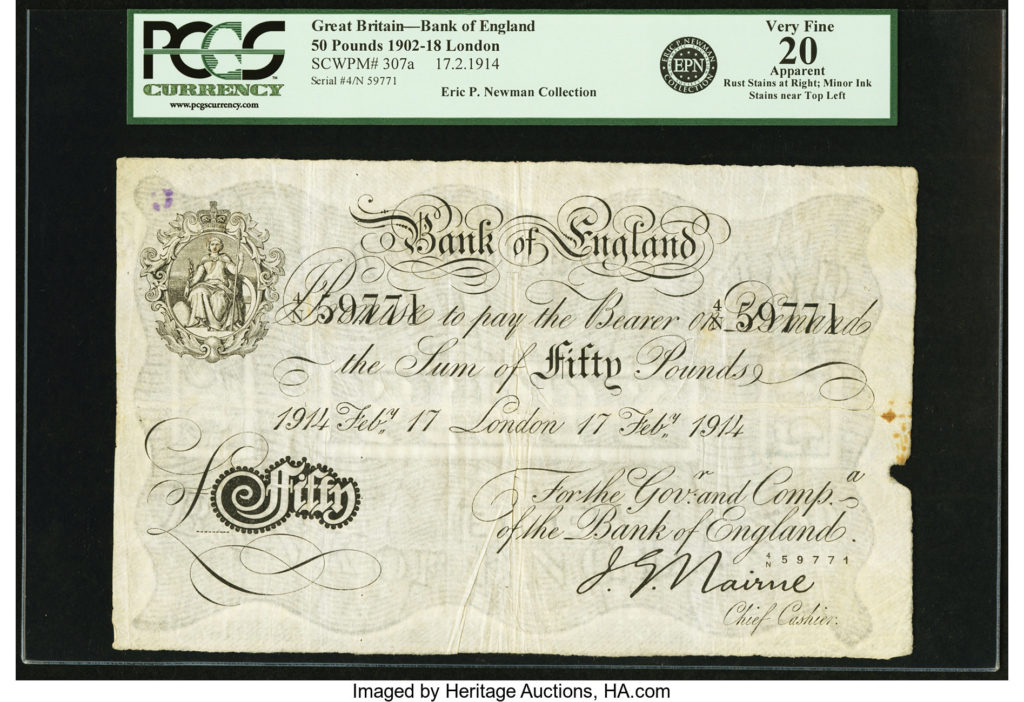

The venerable Bank of England, established in 1694, was known colloquially as “The Old Lady of Threadneedle Street.” This moniker derived from its address in Central London and the English propensity to “tut tut” anything considered disdainful. She took deposits, made loans and financed wars. None of the directors was a banker or even an economist. It was essentially merchant/businessmen who guarded the precious pound sterling, the lifeblood of the economy.

In August 1931, the bank issued an odd press release: “The governor of the Bank of England has been indisposed as a result of the exceptional strain to which he has been subjected in recent months. Acting on medical advice, he has abandoned all work and has gone abroad for rest and change.” That governor was Montagu Norman, the last of the four great Central Bankers (Britain, France, Germany and the United States) to still be alive. Governor Norman had a strange aversion to the press and was notorious for his clever ways to avoid them.

So it was a surprise when he openly explained his trip by ship to Canada: “I need a rest … suffered very difficult times … my health is poor, etc.” What he failed to mention was his incapacitation due to a nervous breakdown or that the world’s financial system was on the verge of collapse. This was especially true of the European banks, where he was revered as the world’s most powerful banker and, as he would later be forced to admit, he was unquestionably “the dictator of European currency,” a role he cherished to all others.

The bank’s press release had been received in Asia, the United States and, naturally, Europe and had further spooked anxious investors since this man was considered the thought leader of “the most exclusive club in the world” … Central Bankers. And 1931 was just the second year of what would become the unprecedented Great Depression that followed the collapse of the U.S. stock market on “Black Tuesday” in 1929. The effect on the United States can be explained by four simple indices from 1929-32: industrial production (46 percent), wholesale prices (32 percent), foreign trade (70 percent), and unemployment (607 percent!).

Supply-demand economists typically point to the event when a stock-market bubble bursts (as in the U.S.) and results in bank failures, bankruptcies and widespread economic devastation. Later monetarists led by Milton Friedman point to the contraction in money supply as a bigger culprit. Ex-Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke now agrees with Friedman and we’ve seen the results of quantitative easing during the 2008 Great Recession followed by 10 years of slow recovery.

I have a different perspective. The cause was pure greed. “Virtual casinos” inside banks were making big bets using customers’ money and outrageous leverage. A housing bubble combined with subprime lending was accompanied by exotic structured products like collateralized debt swaps, mortgage-backed securitization, and a slew of other complicated derivatives that nobody truly understood. They were approved by rating agencies and sold to unsuspecting investors (including other financial firms). Once the housing market collapsed, it exposed all the other high commission, risky products.

This difficult-to-understand situation was simplified by writer Michael Lewis in his book and movie The Big Short. My idea is to have him do something similar to our health-care system (which everybody agrees is terrible … like most of the ideas to fix it). I suspect it could all be cleaned up by having a truly transparent price-based system and eliminating an incomprehensible fee structure that lacks an outcome-based tracking system by hospital, doctor or other caregivers. It is too important to leave to Congress.

Mr. Lewis, I hope someone can get your attention … I am busy this week.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].