By Jim O’Neal

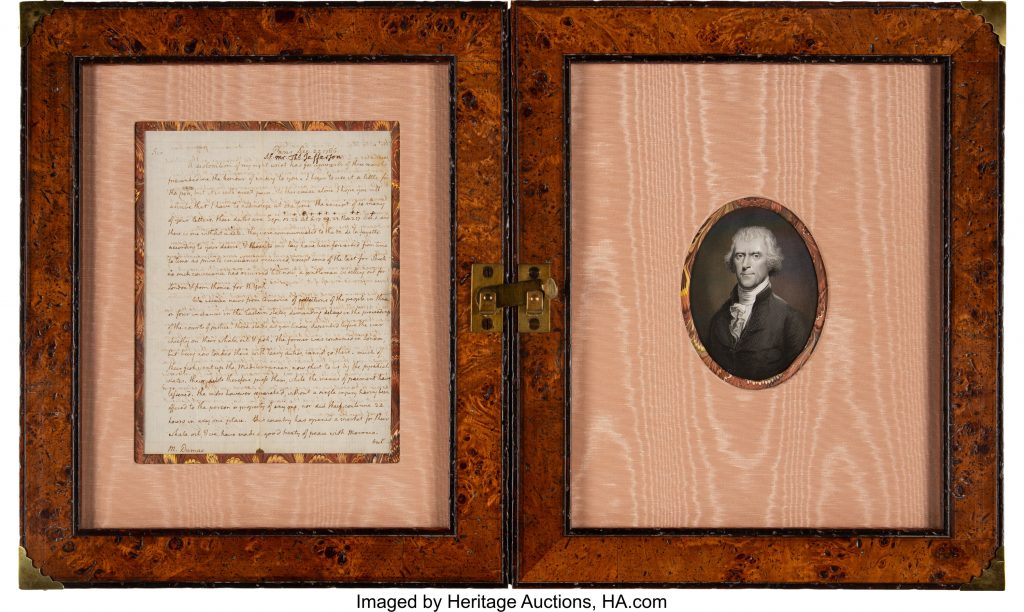

I made a mistake 30 years ago when I began reading the six-volume biography of Thomas Jefferson by Dumas Malone. The first volume was published in 1948 –– won the Pulitzer in 1975 –– and ended with volume six in 1981 (The Sage of Monticello). Malone wrote in a chronicled-narrative style that was like reader’s catnip. I felt compelled to pick up any volume … start on any page … and not wonder what came before.

Randomly picking up a volume to read was like opening a box of Cracker Jacks and eagerly looking for a prize, in this case, one of Jefferson’s many exploits: first secretary of state … second vice president … third president … second governor of Virginia … principal author of the Declaration of Independence … envoy to France … part–time inventor … doubling the size of the United States for a mere $15 million (Louisiana Purchase) … commissioning the Lewis and Clark Expedition … architect-builder of Monticello … or ending up on sculptor Gutzon Borglum’s Mount Rushmore with George Washington, Abraham Lincoln and Teddy Roosevelt.

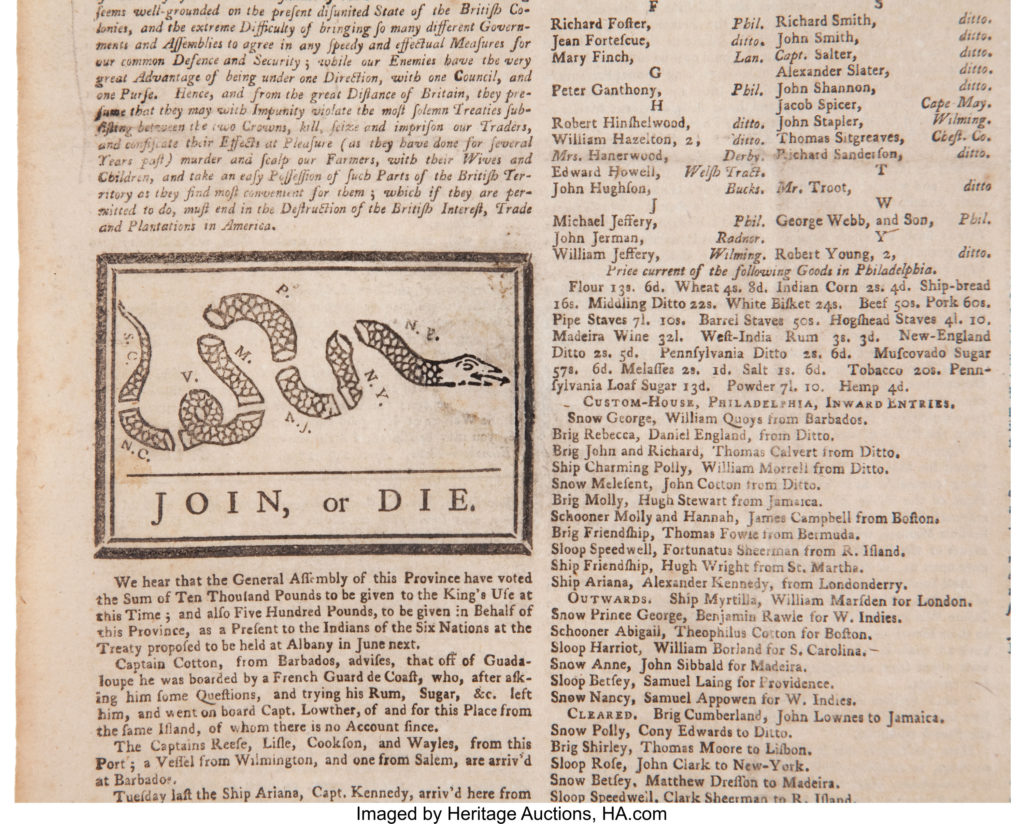

Now, while becoming addicted to Governor Cuomo’s daily Covid-19 status reports, it has stirred old memories of Thomas Jefferson and I wonder what he would think about New York City with its millions of people, tall skyscrapers, massive hospital networks and the plague that has immobilized this amazing city. Early American cities were walking cities since only the affluent owned horses. As a result, beyond a few square miles, they were generally impractical. With the advent of crude mass transit like the omnibus (a wagon or small bus pulled by horses), cities expanded into larger metro areas.

By 1855, there were 700 omnibus lines in a few cities transporting 120,000 passengers a day on bumpy, hand-carved cobblestone roads. This soon improved with the introduction of steel rails. By the 1880s, there were 525 horse–drawn rail lines in 325 cities. However, in addition to street pollution, horses broke down in alarming numbers, bringing an end to the production of buggy whips.

The first electric trolley debuted in 1888 in Richmond, Va. Horses were quickly replaced by electricity and as early 1902, 97 percent of urban transit had been electrified. More than 2 billion passengers were riding on 22,000 miles of electric rails annually. Steam–powered railroads, first introduced in the 1830s, continued to play an important role in transportation, but sheer size limited their use in cities with small, uneven roads. As the 19th century ended, electric trolleys dominated urban transportation, as steam–powered locomotives focused on regional and transcontinental uses.

Yet America’s largest cities, especially New York, had been trying to incorporate railroads as early as 1850. First was a rail line that followed the contours of the Hudson River and catered primarily to commuters. Then NYC introduced an elevated platform with full-size trains, electrified with a third rail providing the power and traversing above the city streets. Chicago and Boston tried similar versions until the 20th century introduced a new-modern concept for train transit.

New York City pioneered the first subway: full-size trains in massive tunnels that had been dug under city streets. The maiden trip was on Oct. 2, 1904, and eventually expanded to include 468 stations and 656 miles of commercial track. Thus, the world–famous NYC subway system that we know today … and a detour to pose a question asked by historian Carl Becker: “What is still living in the political philosophy of Thomas Jefferson?” and your host’s amateurish reply.

The first blow was the Civil War, which destroyed the political primacy of the South … slavery and the doctrine that the states were sovereign agents bound together in a federal compact. Then the 1890 census revealed that the frontier phase of America’s history, made possible by Jefferson, was gone. The 1920 census reported the majority of American citizens lived in urban rather than rural areas. These demographic changes transformed Jefferson’s agrarian vision into a nostalgic memory.

Then the 1930s New Deal capped the urbanization, industrialization and increased density of the population. Roosevelt’s appropriation of Jefferson as a New Deal Democrat has been called “one of the most inspired acts of political thievery in American history.” In fact, the New Deal signaled the death knell for Jefferson’s cherished concept of a minimalist, centralized federal government. Undoubtedly, the massive military buildup to fight the Cold War was precisely the kind of “standing army” that Jefferson truly abhorred.

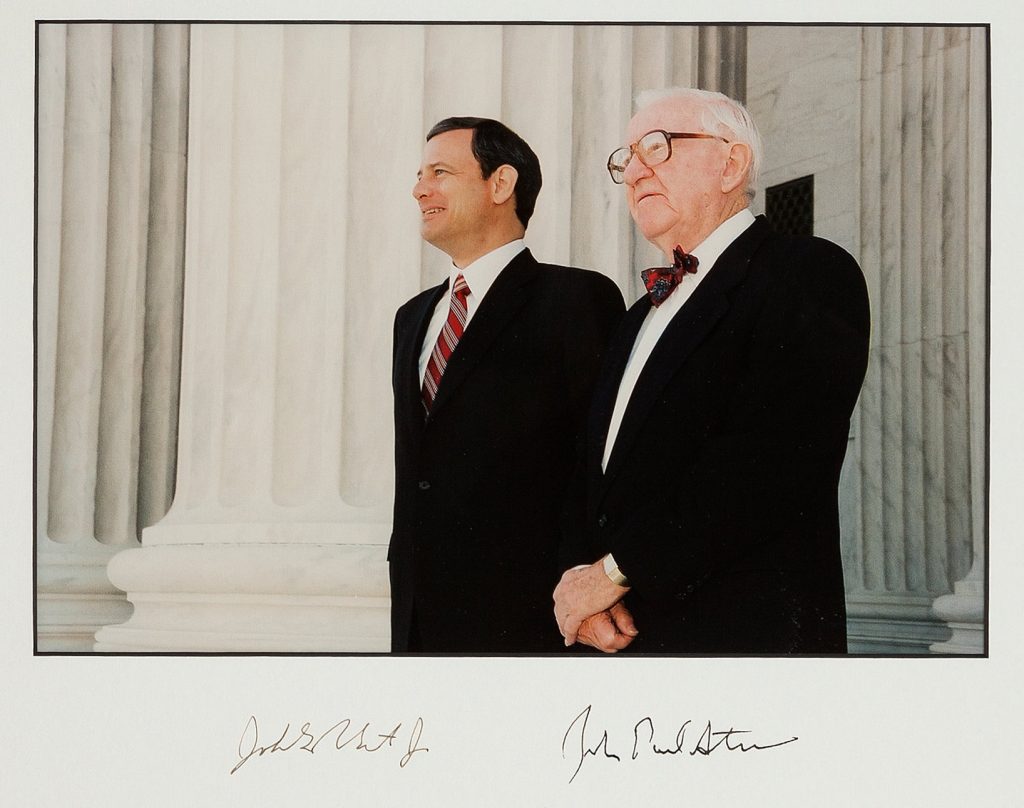

Lastly, of course, was the modern Supreme Court decision in 1954 in Brown v. Board of Education (Topeka, Kan.). This was followed by all the other decisions regarding an equal, multiracial society. The intrusion into regular order made Jefferson’s belief in legal and physical separation of blacks and whites a literal anachronism. However, I suspect Mr. Jefferson, ever the pragmatic statesman, would observe that we should liberate ourselves from the dead hands of ancestors’ or predecessors’ ancient views and seek our own.

Personally, I prefer Ronald Reagan’s uplifting words that we “pluck a flower from Thomas Jefferson’s life and wear it on our soul forever.”

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].