By Jim O’Neal

In August 1945, a historic event occurred: Foreign forces occupied Japan for the first time in recorded history. It was, of course, the end of World War II and cheering crowds were celebrating in the streets of major cities around the world as peace returned to this little planet.

A major factor in finally ending this long, costly war against the Axis powers of Germany and Japan was, ultimately, the use of strategic bombing. An essential element was the development of the B-29 bomber – an aircraft not even in use when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in 1941, forcing a reluctant United States into a foreign war. Maybe it was hubris or fate, but the attack was a highly flawed decision that would not end well for the perpetrators.

The concept of war being waged from the air dates to the 17th century when several wrote about it while speculating on when or where it would begin. The answer turned out to be the Italo-Turkish War (1911-12), when an Italian pilot on Oct. 23, 1911, flew the first aerial reconnaissance mission. A week later, the first aerial bomb was dropped on Turkish troops in Libya. The Turks responded by shooting down an airplane with rifle fire.

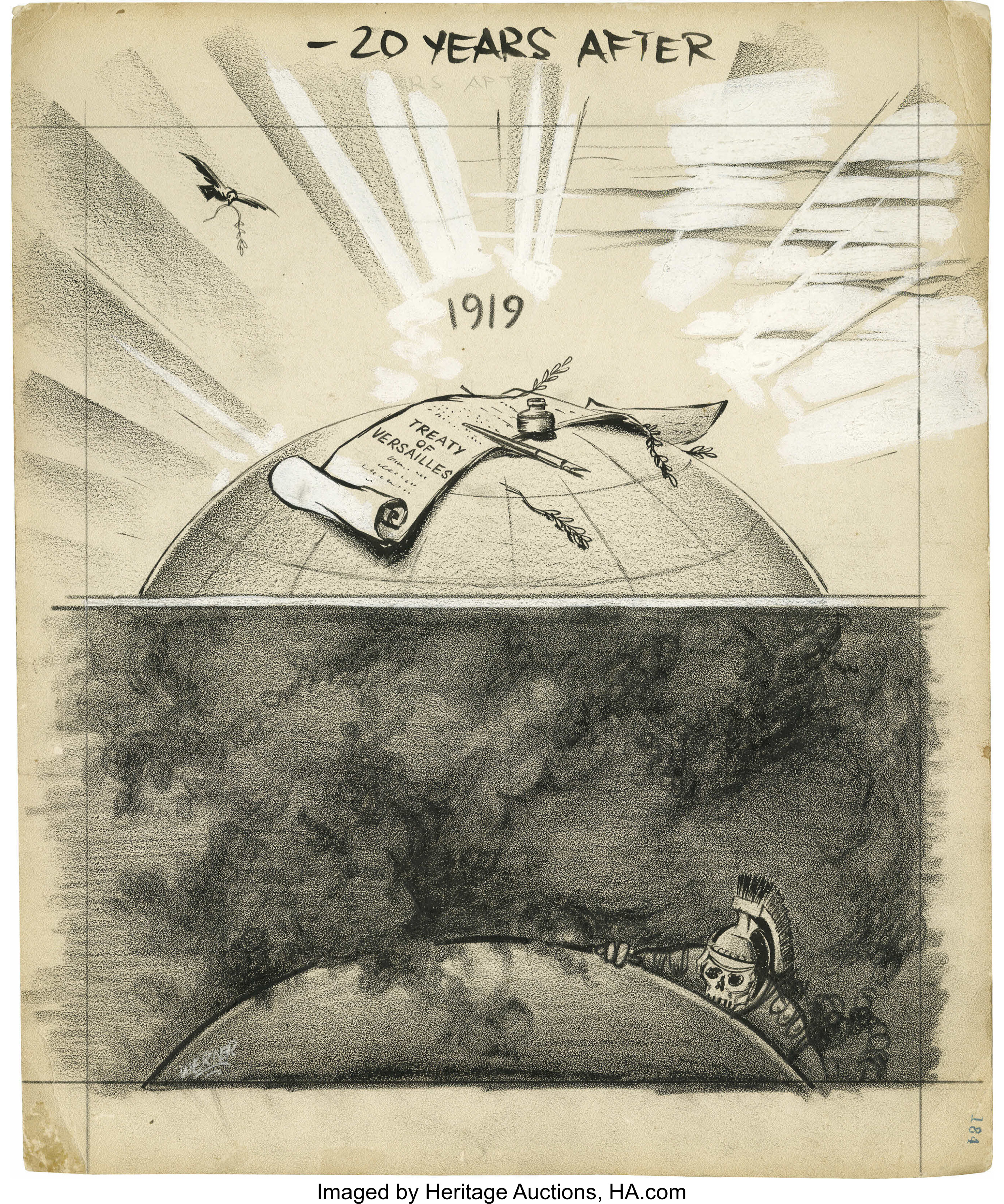

As World War I erupted seemingly out of nowhere, the use of airplanes became more extensive. However, for the most part, the real war was still being waged on the ground by static armies. One bitter legacy of this particular war was the frustration over the futility and horror of trench warfare, which was employed by most armies. Many experts knew, almost intuitively, that airplanes could play a role in reducing the slaughter of trench warfare and a consensus evolved that airplanes could best be used as tactical army support.

However, in the 20-year pause between the two great wars, aviation technology improved much faster than other categories of weaponry. Arms, tanks, submarines and other amphibious units were only undergoing incremental changes. The airplane benefited by increased domestic use and major improvements in engines and airframes. The conversion to all-metal construction from wood quickly spread to wings, crew positions, landing gear and even the lowly rivet.

As demand for commercial aircraft expanded rapidly, increased competition led to significant improvements in speed, reliability, load capacity and, importantly, increased range. Vintage bombers were phased out in favor of heavier aircraft with modern equipment. A breakthrough occurred in February 1932 when the Martin B-10 incorporated all the new technologies into a twin-engine plane. The new B-10 was rated the highest performing bomber in the world.

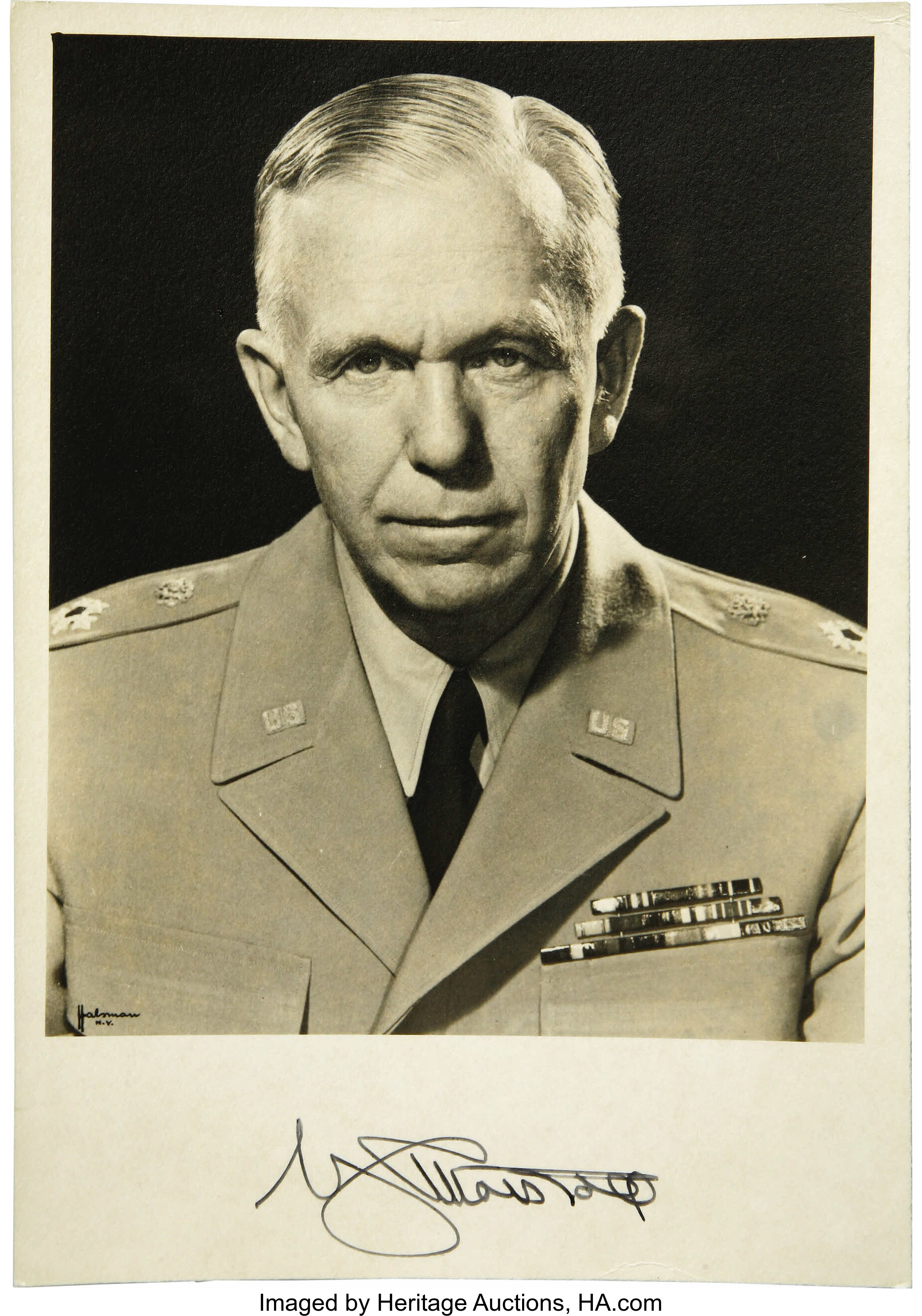

Then, in response to an Air Corps competition for multi-engine bombers, Boeing produced a four-engine model that had its inaugural flight in July 1935. It was the highly vaunted B-17, the Flying Fortress. Henry “Hap” Arnold, chief of the U.S. Army Air Forces, declared it was a turning point in American airpower. The AAF had created a genuine air program.

Arnold left active duty in February 1946 and saw his cherished dream of an independent Air Force become a reality the following year. In 1949, he was promoted to five-star general, becoming the only airman to achieve that rank. He died in 1950.

War planning evolved with the technology and in Europe, the effectiveness of strategic long-range bombing was producing results. By destroying cities, factories and enemy morale, the Allies hastened the German surrender. The strategy was comparable to Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman’s “March to the Sea” in 1864, which added economic and psychological factors to sheer force. Air power was gradually becoming independent of ground forces and generally viewed as a faster, cheaper strategic weapon.

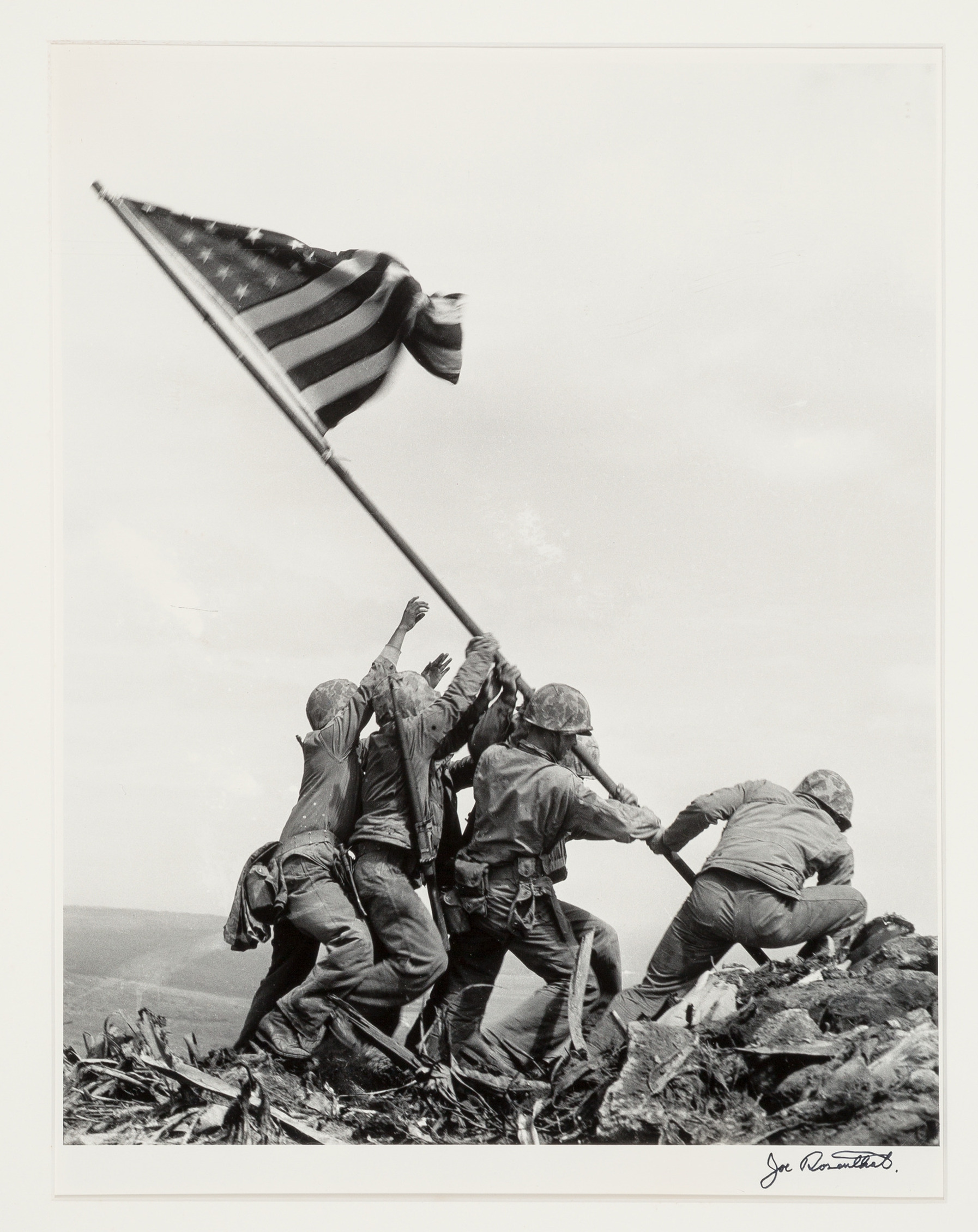

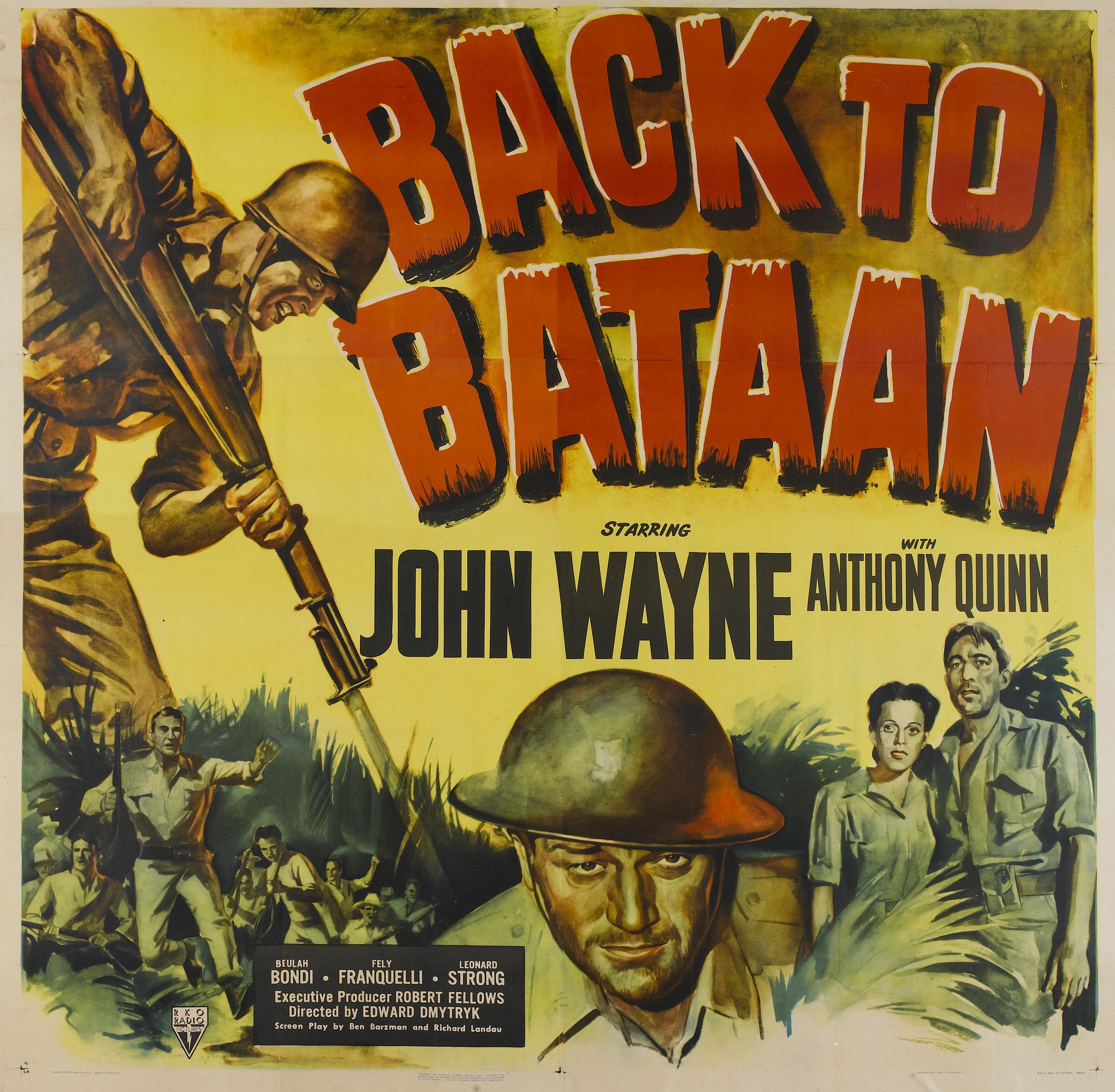

After V-E Day, it was time to force the end of the war by compelling Japan to surrender. The island battles that led toward the Japanese mainland in the Pacific had ended after the invasion of Okinawa on April 1, 1945, and 82 days of horrific fighting that resulted in the loss of life for 250,000 people. This had been preceded by the March 9-10 firebombing of Tokyo, which killed 100,000 civilians and destroyed 16 square miles, leaving an estimated 1 million homeless.

Now for the mainland … and the choices were stark and unpleasant: either a naval blockade and massive bombings, or an invasion. Based on experience, many believed that the Japanese would never surrender, acutely aware of the “Glorious Death of 100 Million” campaign, designed to convince every inhabitant that an honorable death was preferable to surrendering to “white devils.” The bombing option had the potential to destroy the entire mainland.

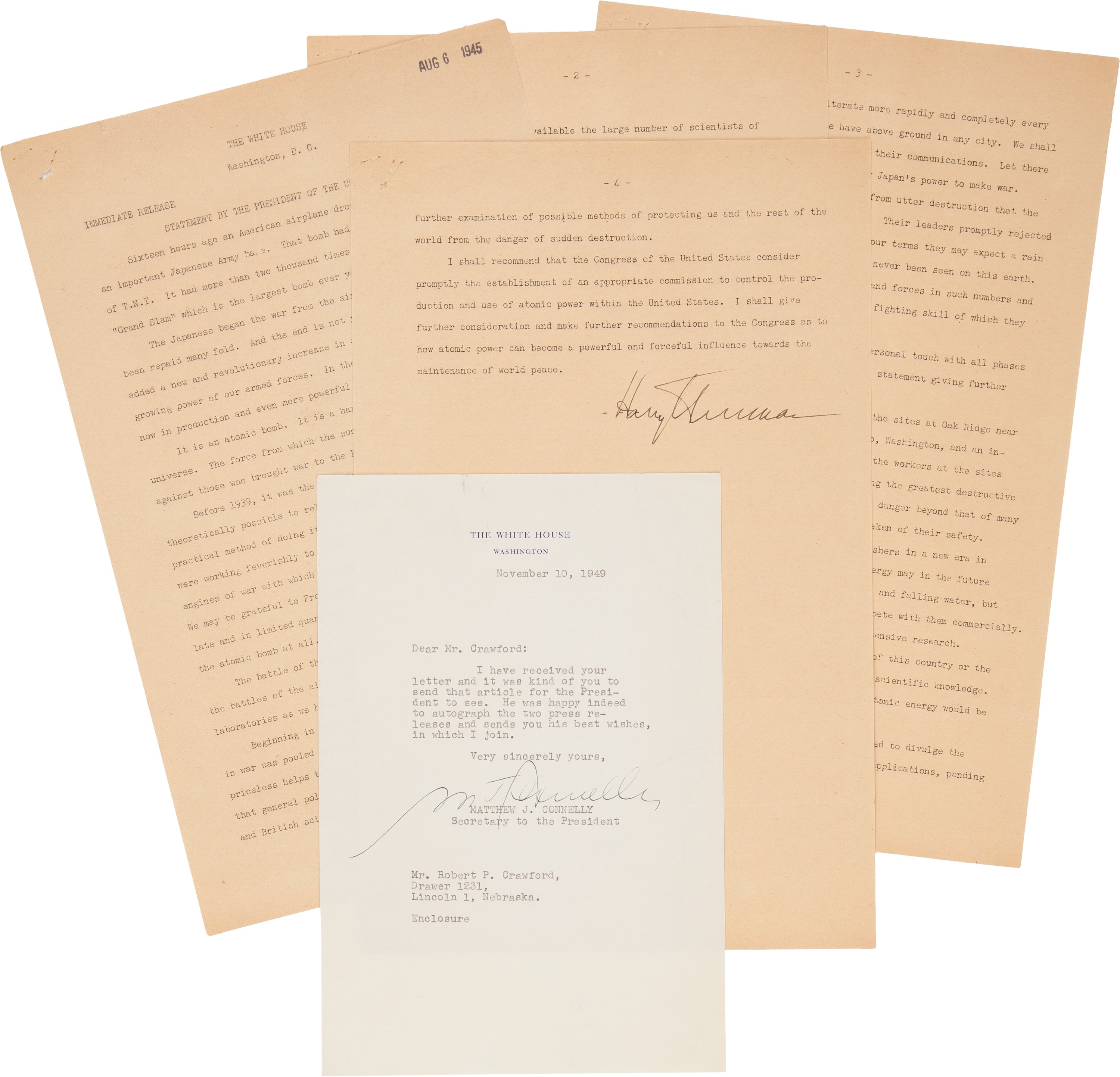

The decision to use the atomic bomb on Hiroshima (Aug. 6) and Nagasaki (Aug. 9) led to the surrender on Aug. 10, paving the way for Gen. Douglas MacArthur to gain agreement to an armistice and 80-month occupation by the United States. Today, that decision still seems prudent despite the fact we only had the two atomic bombs. Japan has the third-largest economy in the world at $5 trillion and is a key strategic partner with the United States in the Asia-Pacific region.

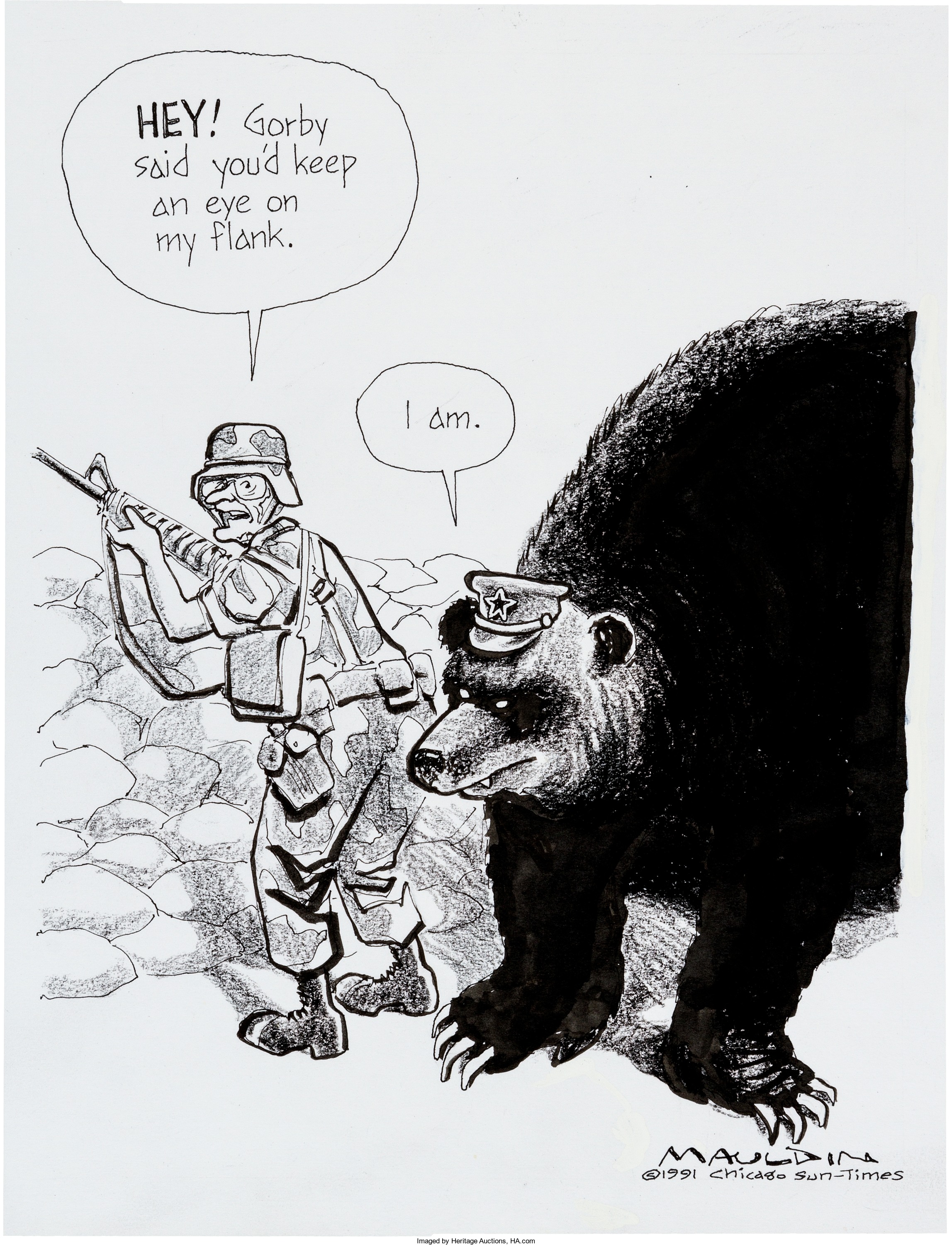

Now about those ground forces in the Middle East…

JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].