By Jim O’Neal

As the states prepared for the first presidential election under the new Constitution, it was clear that George Washington was the overwhelming favorite to become the first president of the United States.

Under the rules, each state would cast two votes and at the February 1789 Electoral College, all 69 Electors cast one of their votes for Washington, making him the unanimous choice of 10 states. Two of the original Colonies (North Carolina and Rhode Island) had not yet ratified the Constitution, and New York had an internal dispute and did not chose Electors in time to participate. Eleven other men received a total of 69 votes, with John Adams topping the list with 34 votes, slightly less than 50 percent. He became the first vice president.

Four years later, there were 15 states (Vermont and Kentucky) and the Electoral College increased to 132 Electors. Again, Washington was elected president unanimously, with 132 votes. Adams was also re-elected with 77 votes, besting George Clinton, Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr. All three of the runner-ups would later become vice presidents, with Clinton serving a term for two different presidents (Jefferson and Madison). Jefferson had cleverly picked Clinton as his VP due to his age, correctly assuming Clinton would be too old to secede him … thus ensuring that Secretary of State James Madison would be the logical choice. Clinton would actually be the first VP to die in office.

Two-time Vice President John Adams would finally win the presidency on his third try after Washington decided not to seek a third term in 1796. Still, Adams barely squeaked by, defeating Jefferson 71-68. Jefferson would become vice president after finishing second. It was during the Adams presidency that the federal government would make its final move to the South after residing first in New York City and then Philadelphia.

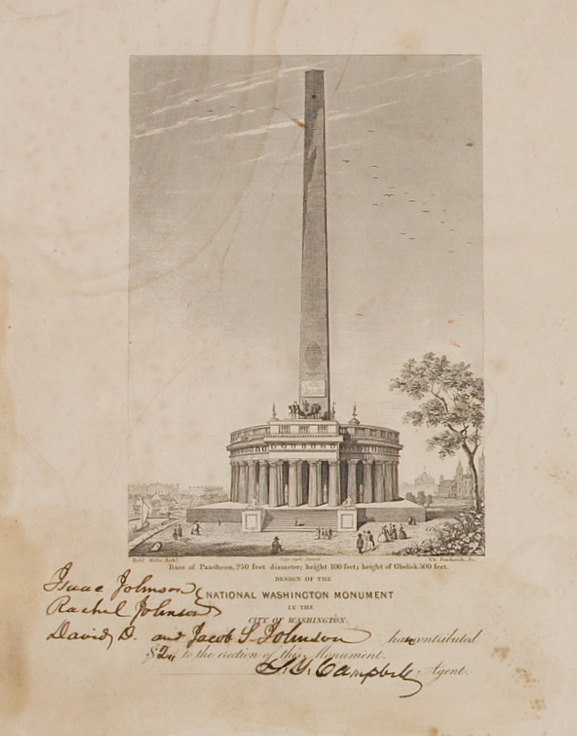

This relocation was enabled by the 1790 Residence Act, a compromise that was brokered by Jefferson with Alexander Hamilton and James Madison, with the proviso that the federal government assume all remaining state debts from the Revolutionary War. In addition to specifying the Potomac River area as the permanent seat of the government, it further authorized the president to select the exact spot and allowed a 10-year window for completion.

Washington rather eagerly agreed to assume this responsibility and launched into it with zeal. He personally selected the exact spot, despite expert advice against it. He even set the stakes for the foundation himself and carefully supervised the myriad details involved during actual construction. When the stone walls were rising, everyone on the project assembled, laid the cornerstone and affixed an engraved plate. Once in the mortar, the plate sank and has never been located since. An effort was made to find it on the 200th anniversary in 1992. All the old maps were pored over and the area was X-rayed … all to no avail. It remained undetected.

The project was completed on time and with Washington in his grave for 10 months, plans were made to relocate the White House from Philadelphia. The first resident, President John Adams, entered the President’s House at 1 p.m. on Nov. 1, 1800. It was the 24th year of American independence and three weeks later, he would deliver his fourth State of the Union address to a joint session of Congress. It was the last annual message delivered personally for 113 years. Thomas Jefferson discontinued the practice and it was not revived until 1913 (by Woodrow Wilson). With the advent of radio, followed by television, it was just too tempting for any succeeding presidents to pass up the opportunity.

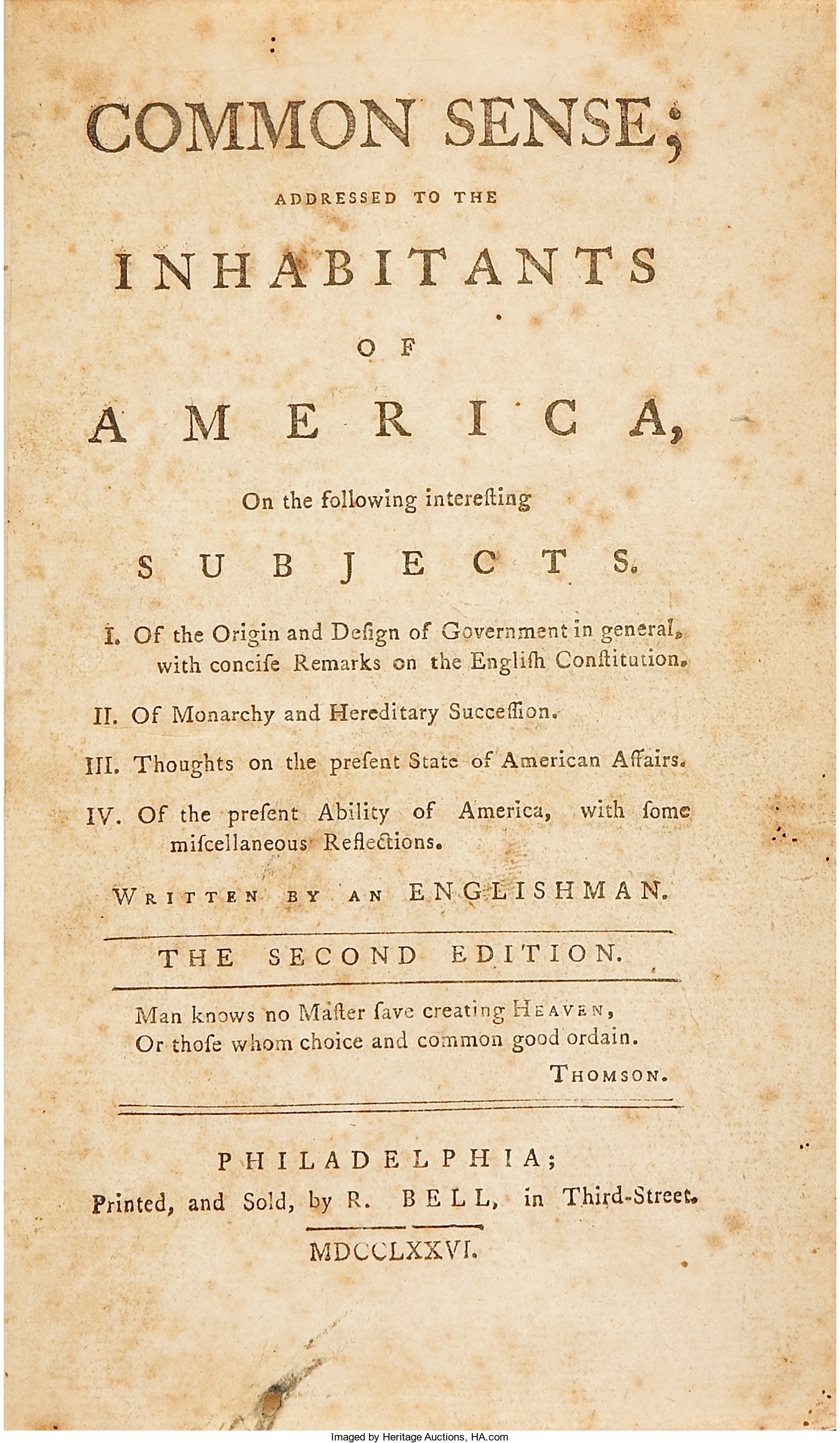

John Adams was a fifth-generation American. He followed his father to Harvard and dabbled in teaching before becoming a lawyer. His most well-known case was defending the British Captain and eight soldiers involved in the Boston Massacre on March 5, 1770. He was not involved in the Boston Tea Party, but rejoiced since he suspected it would inevitably lead to the convening of the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia in 1774.

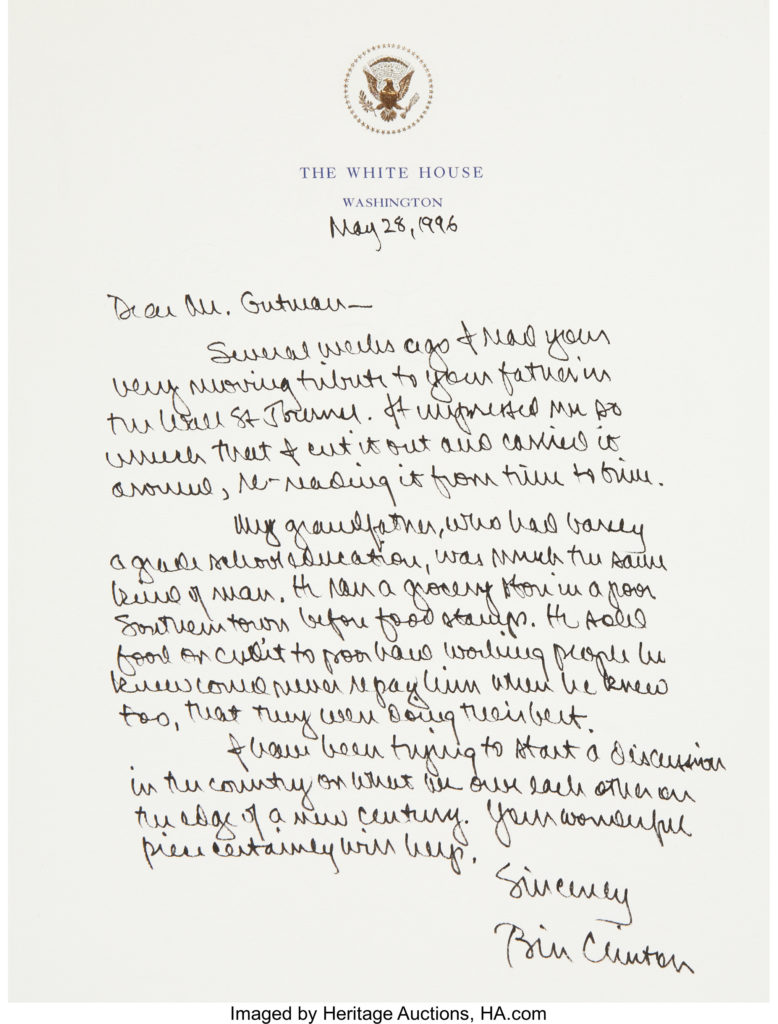

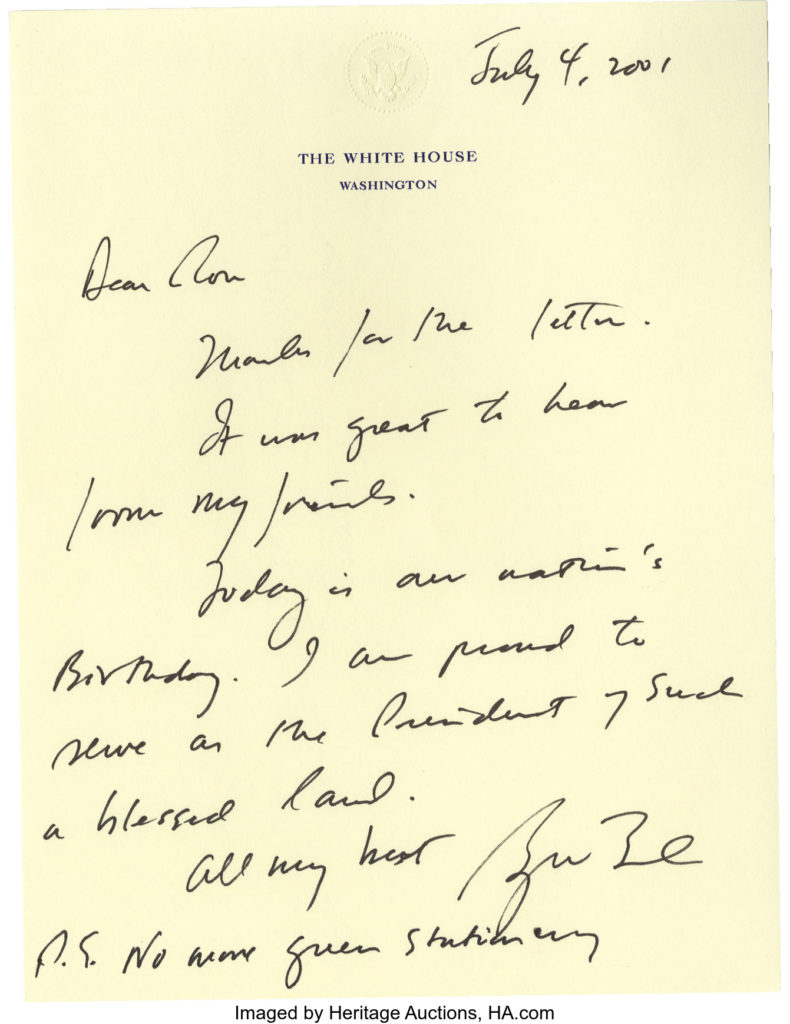

He married Abigail Smith … the first woman married to a president who also had a son become president. Unlike Barbara Bush, she died 10 years before John Quincy Adams actually became president in 1825. Both father and son served only one term. Abigail had not yet joined the president at the White House, but the next morning he sent her a letter with a benediction for their new home: “I pray heaven to bestow the best blessing on this house and on all that shall hereafter inhabit it. May none but honest and wise men ever rule under this roof.” Franklin D. Roosevelt was so taken with it that he had it carved into the State Dining Room mantle in 1945.

Amen.

JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].