By Jim O’Neal

The news broke shortly before 6 p.m. on April 12, 1945. President Franklin Roosevelt had died of a cerebral hemorrhage in Warm Springs, Ga. Within minutes, the bulletin had reached every part of the country. It was almost midnight in London, but in Berlin, it was already the next day, where it was (ominously) Friday the 13th. However, Joseph Goebbels interpreted it as a lucky turning point when he telephoned Adolf Hitler. He was already devising ways to turn this to Germany’s advantage, even as enemy troops closed in on the Third Reich.

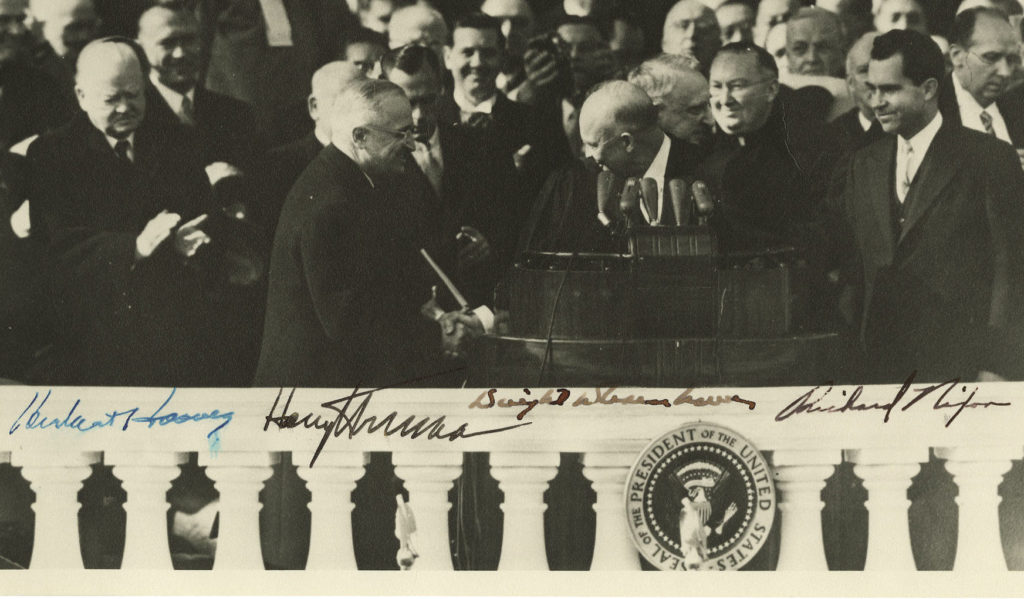

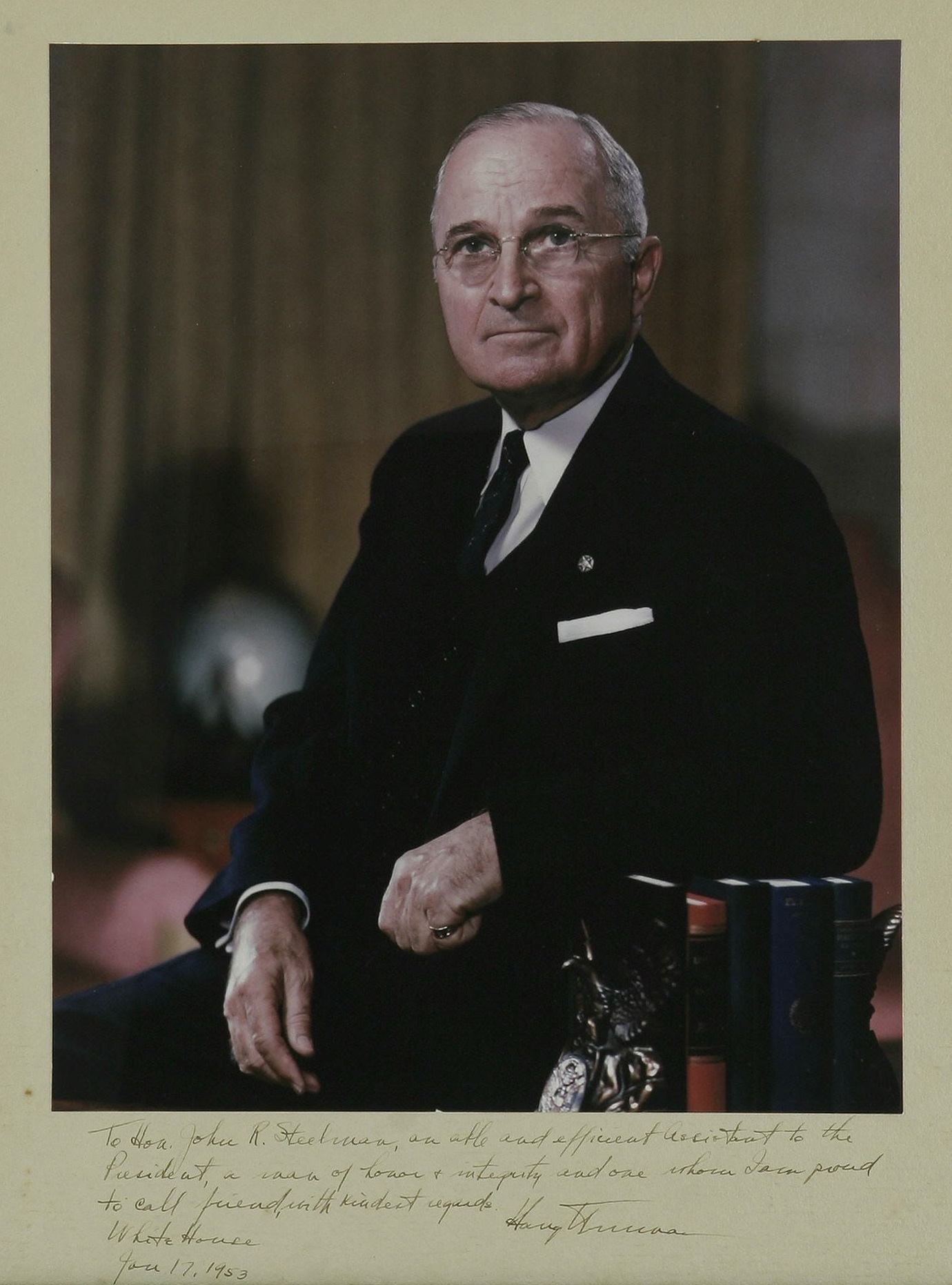

By 7 p.m., Harry Truman, his Cabinet and Bess and Margaret were assembled in the Cabinet Room along with Chief Justice Harlan Stone to administer the oath of office. Within hours of Roosevelt’s death, the country had a new president.

Then the family and the Cabinet were dismissed. Secretary of War Henry Stimson lingered to brief the new president on a matter of extreme urgency. He explained that a new weapon of almost inconceivable power had been developed, but offered no details. Truman had just learned about the existence of the atomic bomb. He canceled a date to play poker and went to bed. It had been a long day.

It was also a long day for America’s top generals: Dwight D. Eisenhower, George S. Patton and Omar Bradley. The shock of losing their trusted commander-in-chief was compounded by genuine concern over Truman’s lack of experience. To make matters worse, they had just seen their first Nazi death camp. All were depressed, but Patton was especially emphatic about his concerns for the future.

The next morning, President Truman arrived at the White House promptly at 9 a.m. It was now April 13, 1945 – 27 years to the day since he had landed at Brest, France (Brittany), as a lowly 1st Lieutenant in the Allied Expeditionary Forces in WWI. Now he was the United States’ commander in chief in the century’s second world war. Everything in the Oval Office was eerily just as FDR had left it. He sat in the chair behind the desk and quietly pondered the challenges he had inherited. Downstairs, the White House staff was frantically coping with the press, the jangle of telephones, and wondering what to do next.

After a routine update on the status of the war, Truman surprised everyone by announcing he was going to the Capitol to “have lunch with some of the boys” … 17 congressmen to be exact. After a few drinks and lunch, he told the group he felt overwhelmed and emphasized he would need their help. Then he stepped out to meet the assembled press and made his now famous remarks: “Boys, if you ever pray, pray for me now. I don’t know whether you fellows ever had a load of hay fall on you, but when they told me yesterday what had happened, I felt like the moon, the stars and all the planets had fallen on me.”

Less than four months later, in August 1945, the man from Independence, Mo., now confident and in control, dropped his own bombshell when he broadcast to the nation:

“Sixteen hours ago, an American airplane dropped one bomb on Hiroshima,” the president said, adding, “We are now prepared to obliterate more rapidly and completely every productive and enterprise the Japanese have above ground in any city. We shall destroy Japan’s power to make war. … If they do not now accept our terms, they may expect a rain of ruin from the air the like of which has never been seen on this earth.”

The buck DID stop here, just as the little sign on his desk promised.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].