By Jim O’Neal

As federal war-game planners considered their objectives in mobilizing a West Coast battle response, railroads were quickly ruled out because they could not carry the amount of equipment involved and some of the weapons, especially tanks, were too heavy for trains and tracks.

Since the Army already had plenty of wheeled and tracked vehicles, dispatching a test expedition by road and having a Motor Transport Corps drive the convoy could prove, once and for all, the superiority of wheels over hoofs or railways. Inexplicably, they failed to include any assumptions about the condition of the roads en route.

At the appointed time in 1919, the convoy gathered at a monument by the South Lawn of the White House. The column was three miles long and consisted of 79 vehicles, including 34 heavy trucks, oil and water pumpers, a mobile blacksmith shop, a tractor, staff observation cars, searchlight carriers, a mobile hospital and other wheeled necessities to support the actual war machines.

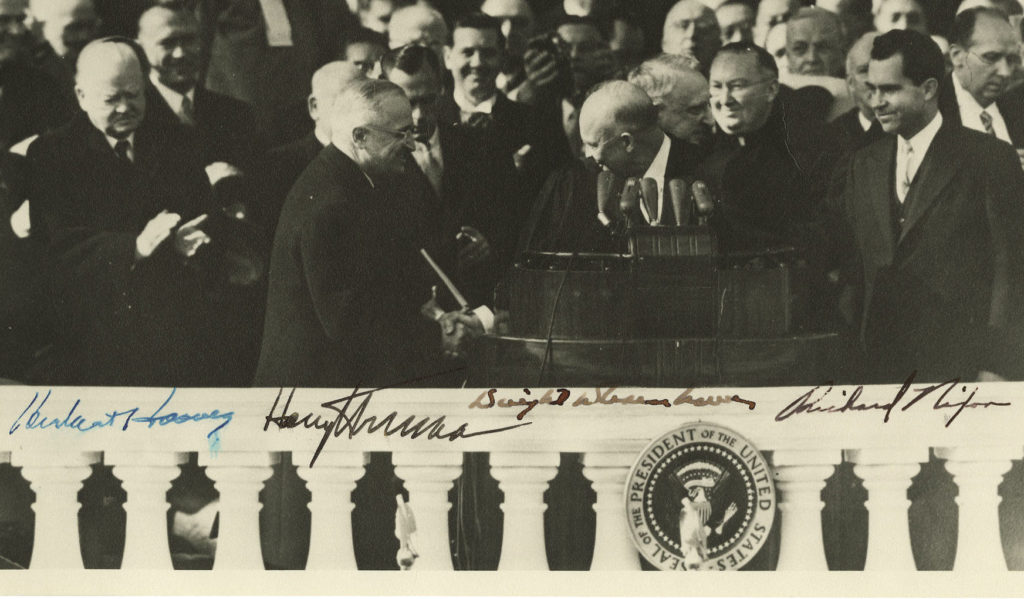

Nine vehicles were wrecked en route and 21 men injured – leaving 237 soldiers, 24 officers and 15 observers – including then-Brevet Lt. Col. Dwight D. Eisenhower (who kept a concise daily diary). When they arrived in Lincoln Park in San Francisco 62 days later, it was undisputed that the conditions of the roads – essentially non-existent west of the Missouri River – would preclude any timely defense of the West Coast and that any Asian enemy would have been victorious in any battles along the way.

The journey left an indelible impression on the young officer from West Point, who would later be Commander-in-Chief of the nation. The Army and Eisenhower had indisputably proved what many in the capital had suspected. The American West had few, if any, roads that were even remotely usable for military or civilian use.

Only when they reached California and beyond the state capital of Sacramento did the roads become great – with macadamized surfaces, proper drainage, road rules, gas stations and tire-repair depots … all in sufficient quantity to service existing needs.

But this did not appease Eisenhower in the slightest. This great convoy, called into action to deal with a hypothetical threat to the country’s vital West Coast, had crossed 3,251 miles of the country at an average speed of 5.6 mph, making any potential response virtually useless. The vehicles were in fine shape and the men brave and intelligent, but the roads were deplorable. If nothing else, Eisenhower wrote, the experience of this expedition should spur the building – as a national effort – of a fast, safe and properly designed system of transcontinental highways.

This led to the creation of America’s Interstate Highway System – the greatest engineering project in world history … an intrinsic network of high-speed roads built with the sole purpose of uniting the corners, edges and center of this vast nation.

Fittingly, “The Dwight D. Eisenhower National Interstate and Defense Highways Act” was authorized by the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 during the second term of the 34th president of the United States. “I LIKE IKE!”

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is President and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as Chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is President and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as Chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].