By Jim O’Neal

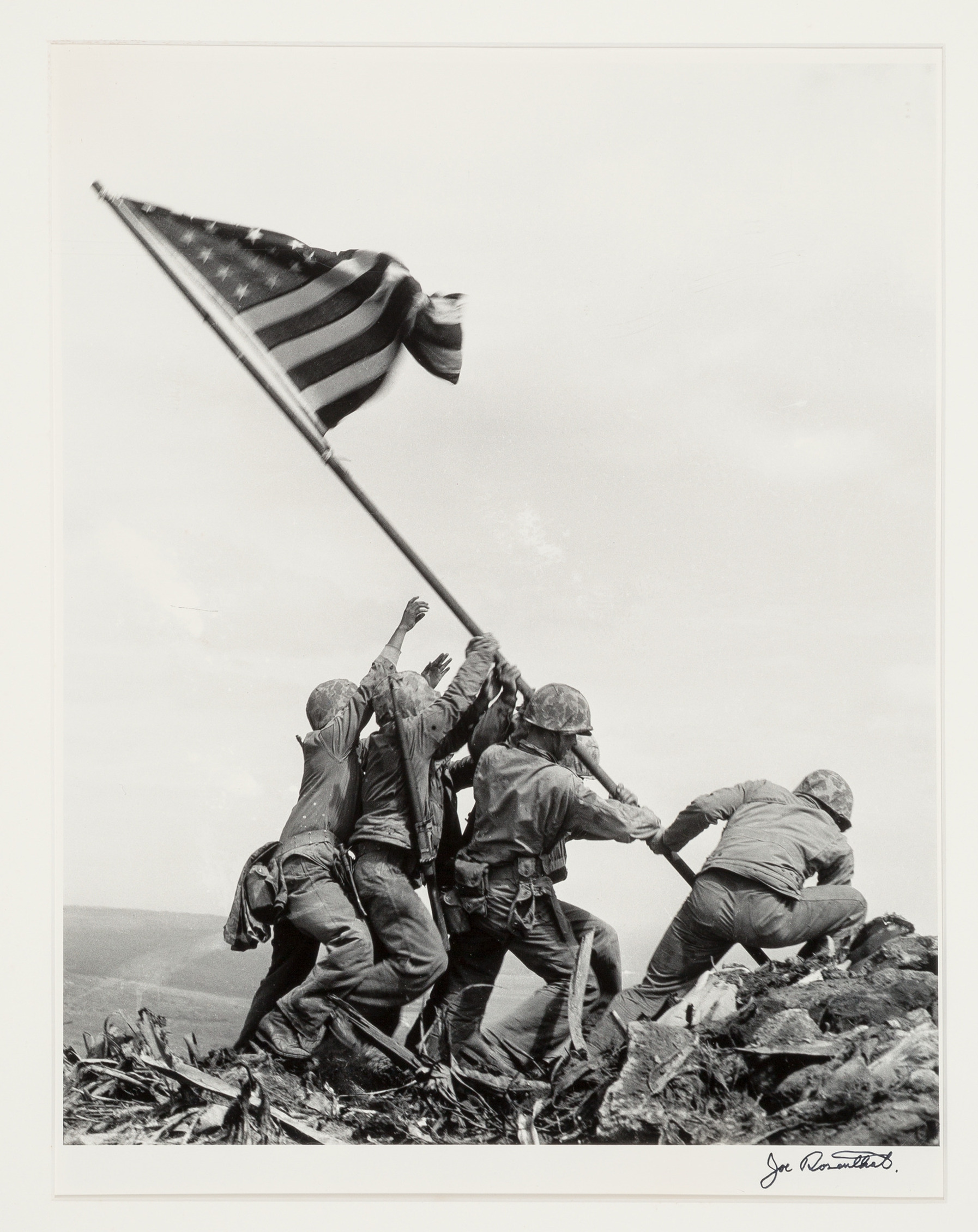

Feb. 23, 1945, was a dramatic day in World War II when six Marines raised the American flag on Mount Suribachi to signal a decisive victory at Iwo Jima. Associated Press photographer Joe Rosenthal was there and his photo “Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima” won him the Pulitzer Prize for photography in 1945 – the only one to ever win in the same year it was published.

One of the Marines who hoisted the flag, Ira Hamilton Hayes, portrayed himself in the 1949 movie The Sands of Iwo Jima, which was nominated for four Academy Awards. It starred John Wayne, who received his first Academy Award nomination for Best Actor. He would have to wait 21 years to actually win one for Best Actor in the movie True Grit. Sadly, Hayes, an American Indian, died in 1955 at the tender age of 32 from alcoholism-related circumstances.

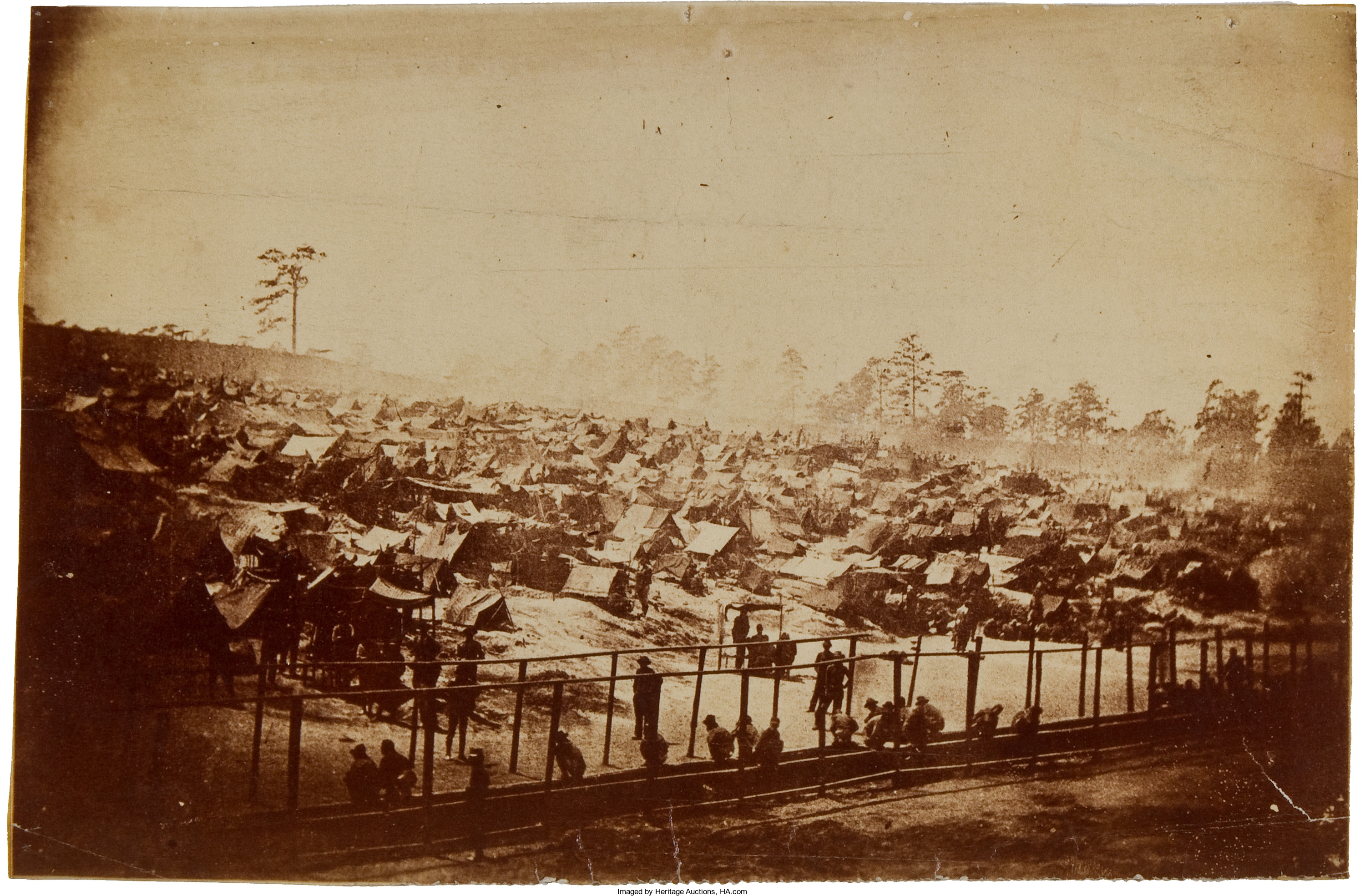

The battle for Iwo Jima was the first U.S. attack on the Japanese Imperial home islands and soldiers defended it tenaciously since it was the first stepping stone to the mainland. Of the 21,000 Japanese troops dug into tunnels and heavily fortified positions, 19,000 were killed as they had made a sacred commitment to fight to their death. There were numerous reports of soldiers committing suicide rather than surrendering, although there was also a curious situation where several actually hid in caves for two years before finally giving up. The battle for the entire island lasted from Feb. 23 until March 26 and it was considered a major strategic victory.

The first word of this momentous news crackled over the radio in odd guttural noises and complex intonations. Throughout the war, the Japanese had been repeatedly baffled and infuriated by these bizarre sounds. They conformed to no linguistic system known to Japanese language experts. The curious sounds were the U.S. military’s one form of communicating that master cryptographers in Tokyo were never able to decipher.

This seemingly perfect code was the language of the American Navajo Indian tribe. Its application in WWII as a clandestine system of communication was one of the 20th century’s best-kept secrets. After a string of cryptographic failures, the military in 1942 was desperate for lines of communication among troops that would not be easily intercepted. In the 1940s, there was no such thing as a “secure line.” All talk had to go out over the public airwaves. Standard codes were an option, but cryptographers in Japan had become adept at quickly cracking them. And there was another problem. The Japanese were also proficient at intercepting short-distance communications – walkie-talkies for example – and then having well-trained English-speaking soldiers either sabotage the message or send out false commands to set up an ambush.

That was the situation in 1942 when the Pentagon authorized one of the boldest gambits of the war by recruiting Navajo code talkers. Because the Navajo lacked technical terms for military artillery, the men coined a number of neologisms specific to their task and their war. Thus, the term for a tank was “turtle,” a battleship was “whale,” a hand grenade was “potato” and plain old bombs were “eggs.”

It didn’t take long for the original 29 recruits to expand to an elite corps of Marines, numbering 425 Navajo code talkers, all from the American Southwest. The talkers were so valuable that they traveled everywhere with personal bodyguards. In the event of capture, they had all agreed to commit suicide rather than allow America’s most valuable tool to fall into the hands of the enemy. If a captured Navajo didn’t follow that grim instruction, the bodyguard was told to shoot and kill the code talker.

Their mission and every detail of their messaging was a secret not even their families knew about. It wasn’t until 1968, when the military felt convinced they would not be needed in the future, that America learned about the incredible contributions a handful of American Indians made to winning history’s biggest war. The Navajo code talkers, sending and receiving as many as 800 error-free messages every day, were widely credited with giving troops the decisive edge at Guadalcanal, Tarawa, Saipan, Iwo Jima and Okinawa.

Semper fi.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].