By Jim O’Neal

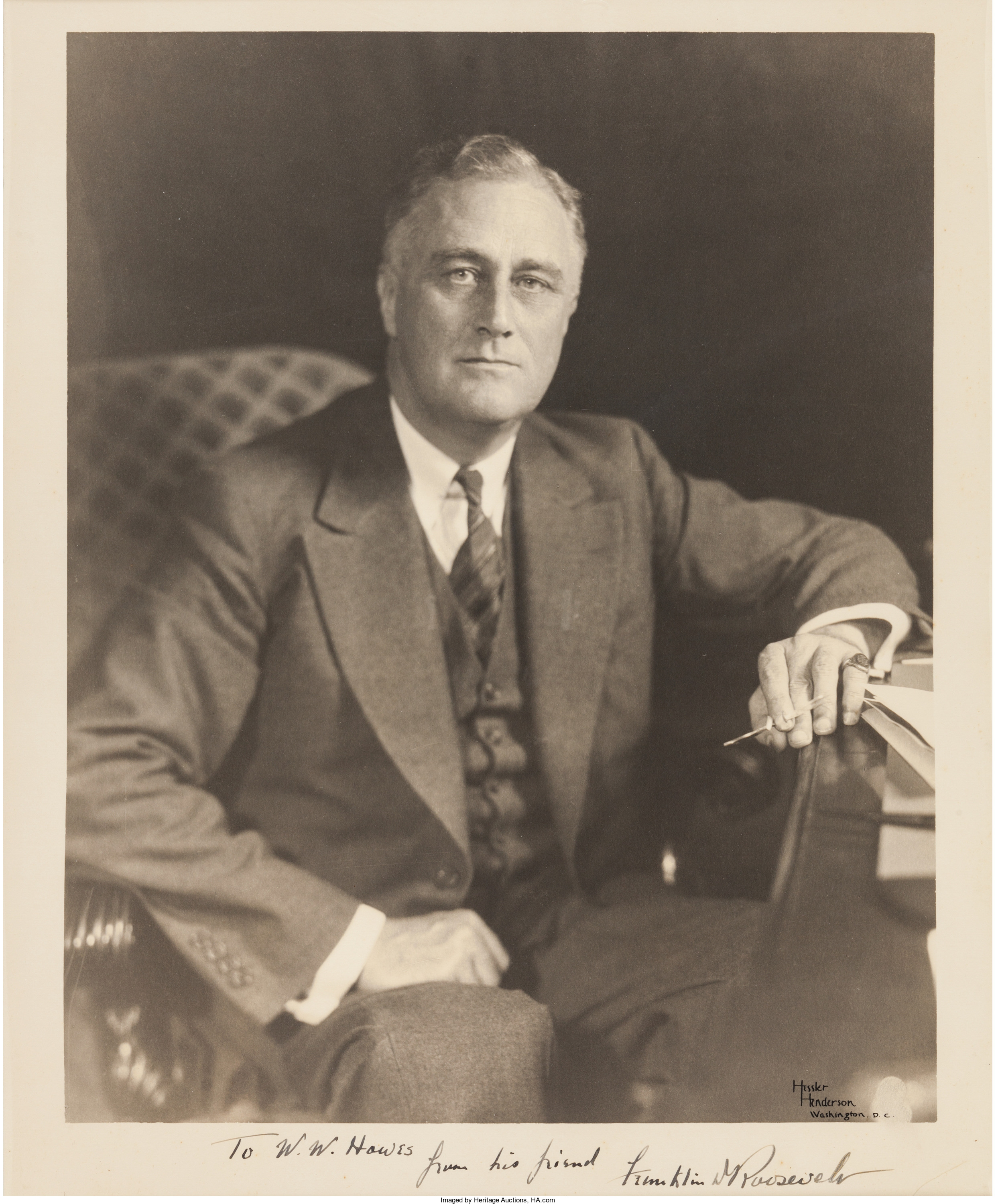

President Franklin D. Roosevelt understood that it was not enough for only him to understand the Great Depression’s grip on the nation. The American people would have to see for themselves the faces of their fellow citizens, their backs against the wall, drained by the struggle to hold families and farms together.

The Depression was in its fourth year. In the neighborhoods and hamlets of a stricken nation, millions of men and women languished in sullen gloom and looked to Washington with guarded hope. Still they struggled to comprehend the nature of the calamity that had engulfed them. At the new Federal Emergency Relief Administration, headed up by Harry Hopkins, rivers of data flowed that measured the Depression’s impact in cold, hard numbers. Shareholders had seen the value of their assets decline by 75 percent since 1929, a colossal financial meltdown affecting the idle rich, struggling neighborhood banks, retirement nest eggs and even university endowments. Five thousand banks failed between the crash and the New Deal’s rescue operations in March 1933, wiping out $7 billion of depositors’ money.

Mortgage loan defaults accelerated – 150,000 homes lost in 1930; 200,000 in 1931; 250,000 in 1932. This stripped millions of people of both shelter and life savings in a single stroke, menacing the balance sheets of thousands of surviving banks. Shrinking real estate prices and tax revenues forced 1,300 municipalities to default, cutting services, payrolls and paychecks. Chicago reduced teacher pay and by 1932-33 cut their pay to zero.

Gross national product fell in 1933 to half of 1929, while capital spending on plant and equipment plummeted to $3 billion from $24 billion. Car production dropped 60 percent and steel was even worse. Mute bands of jobless men drifted through the streets of every American city on the prowl for jobs that didn’t exist.

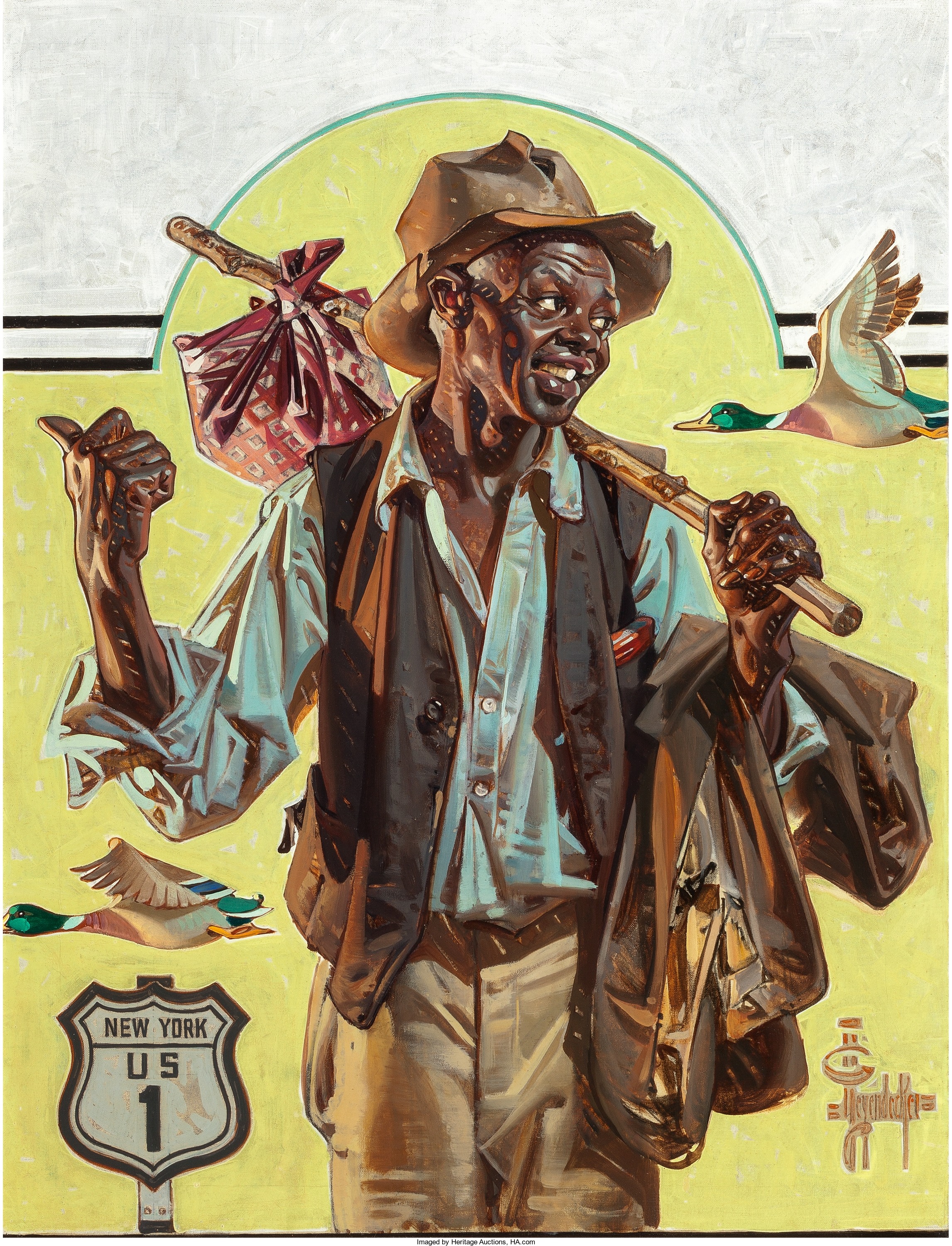

Hardest hit was the countryside. Income for America’s farmers collapsed from $6 billion to $2 billion in three years. Unemployment and reduced wages were the most obvious and fell hardest on the most vulnerable: the young, the elderly, the least educated, the unskilled, and especially on rural Americans, with large numbers of immigrant workers.

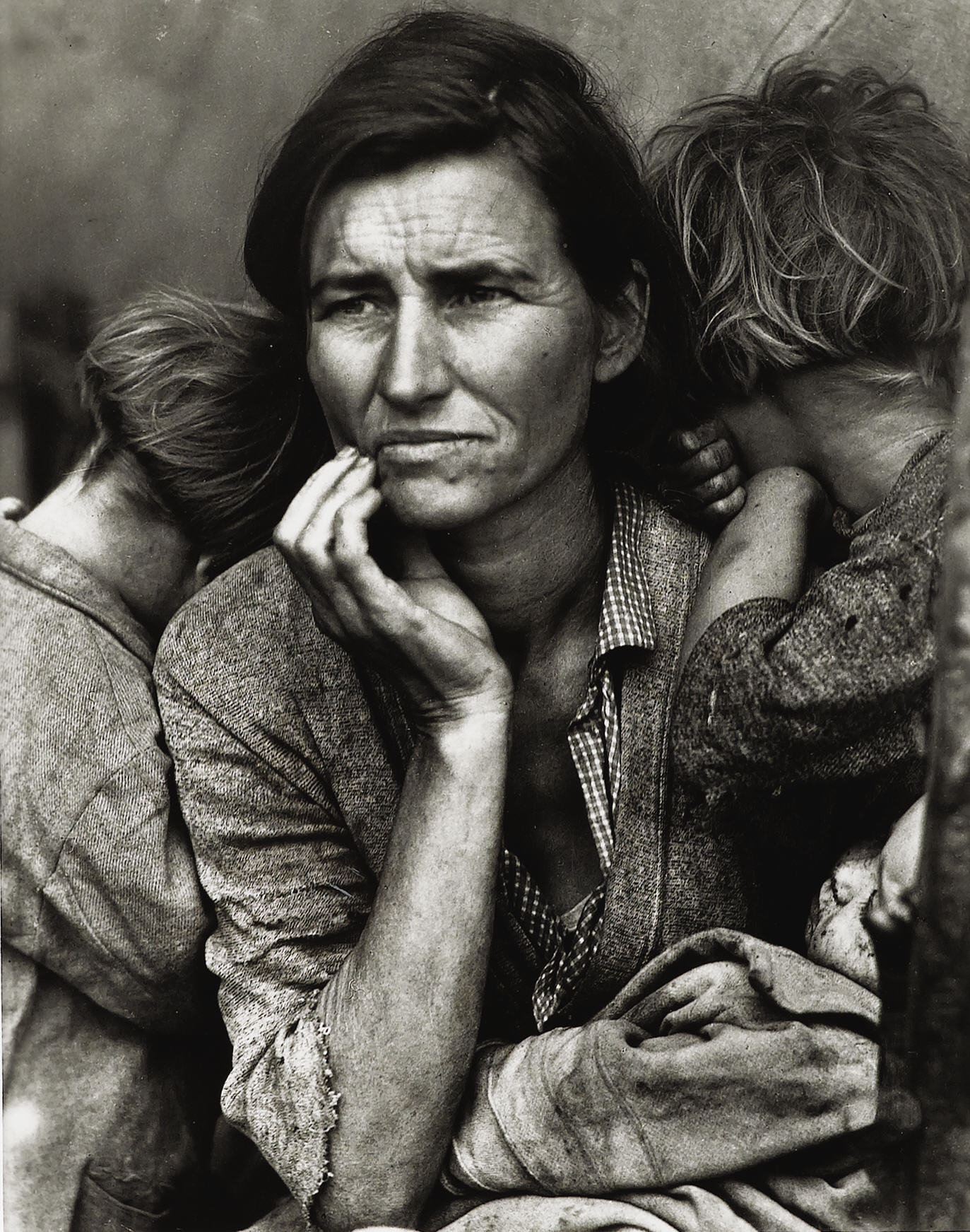

But Hopkins knew that he needed more than sterile economic data to gain the necessary political power to make the structural government changes required. They needed to touch the human face of the catastrophe, taste the metallic smack of the fear and feel the hunger of the unemployed. He convinced Lorena Hickok of the Associated Press in July 1933 to travel the entire nation … talking to a broad swath of Americans and capturing their stories in their own words and in photographs. With FDR’s encouragement, a flood of documentary photographs would be converted into political power on a massive scale. In addition to Hickok, they contracted some of the nation’s finest photographers. Names like Dorothea Lange, Arthur Rothstein, Walker Evans and others would help create the consciousness necessary to mobilize the government’s resources. Their photographs helped create the absolute sense of urgency needed so desperately.

The small, nimble government agency that would support and encourage their photographic mission was the Resettlement Administration – later called the Farm Security Administration (FSA) – under the leadership of Rexford Tugwell, an original member of FDR’s brain trust, and still Assistant Secretary of Agriculture. Importantly, neither the Resettlement Administration nor the FSA had any Congressional oversight. These photographers had the freedom to tell the truth as they saw it. Their photographs are now housed in the Library of Congress and bear witness to what people were enduring, refuting what newspapers had been calling “moochers” or “an invading hoard of the idle.”

Looking at these portraits now, we can see the compassion of the photographers and the dignity of real Americans on the edge. They refuted the charges of those who thought the pictures were political propaganda. In discussions of the work of Dorothea Lange and her husband Paul Taylor, the photographer/curator Thomas Heyman summed it up: “They clung to the hope that what they were doing might be part of the solution.”

The strategy worked and FDR was given a mandate to introduce all aspects of the New Deal, the most expansive role of the federal government into America’s daily life. After the 1936 elections, newspaper editor William Allen White said, “He has all but been crowned by the people.” Still, it would take yet another war to get everybody back to work.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].