By Jim O’Neal

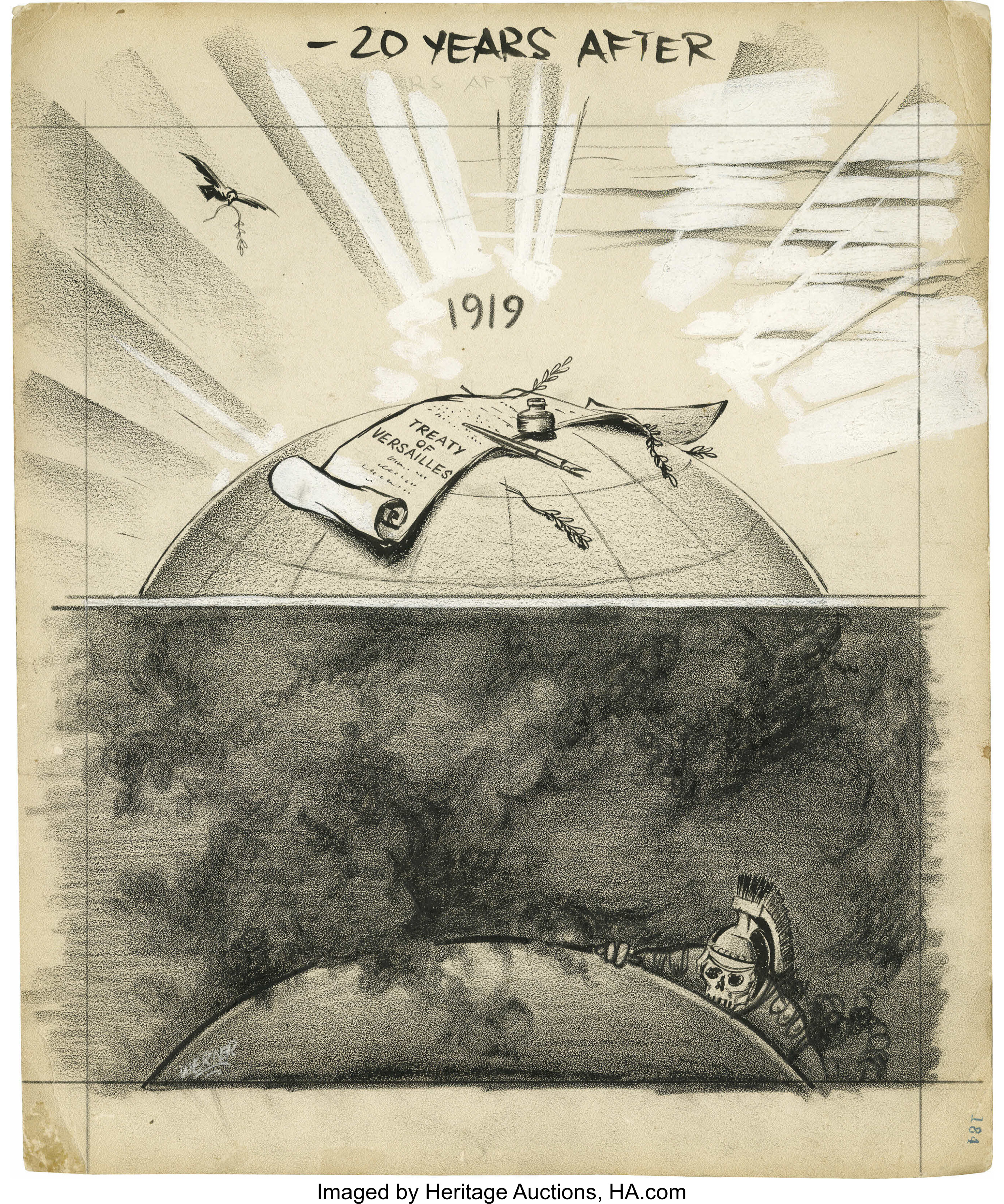

Four years ago, George Clooney, Matt Damon and Bill Murray starred in a movie titled The Monuments Men, about a group of almost 400 specialists who were commissioned to try and retrieve monuments, manuscripts and artwork that had been looted in World War II.

The Germans were especially infamous for this and literally shipped long strings of railroad cars from all over Europe to German generals in Berlin. While they occupied Paris, they almost stripped the city of its fabled art collections by the world’s greatest artists. Small stashes of hidden art hoards are still being discovered yet today.

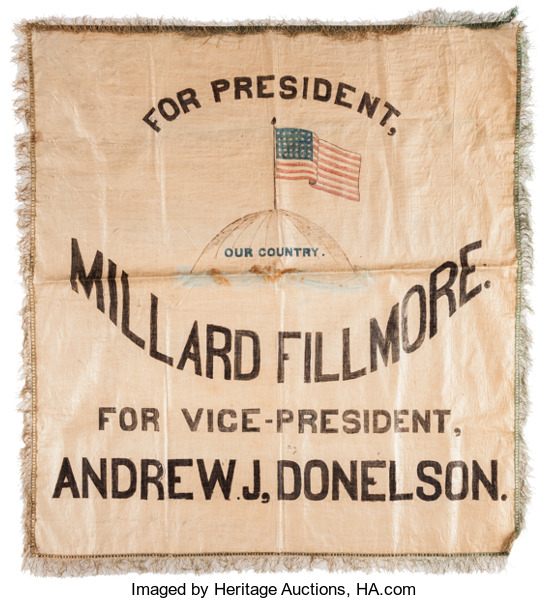

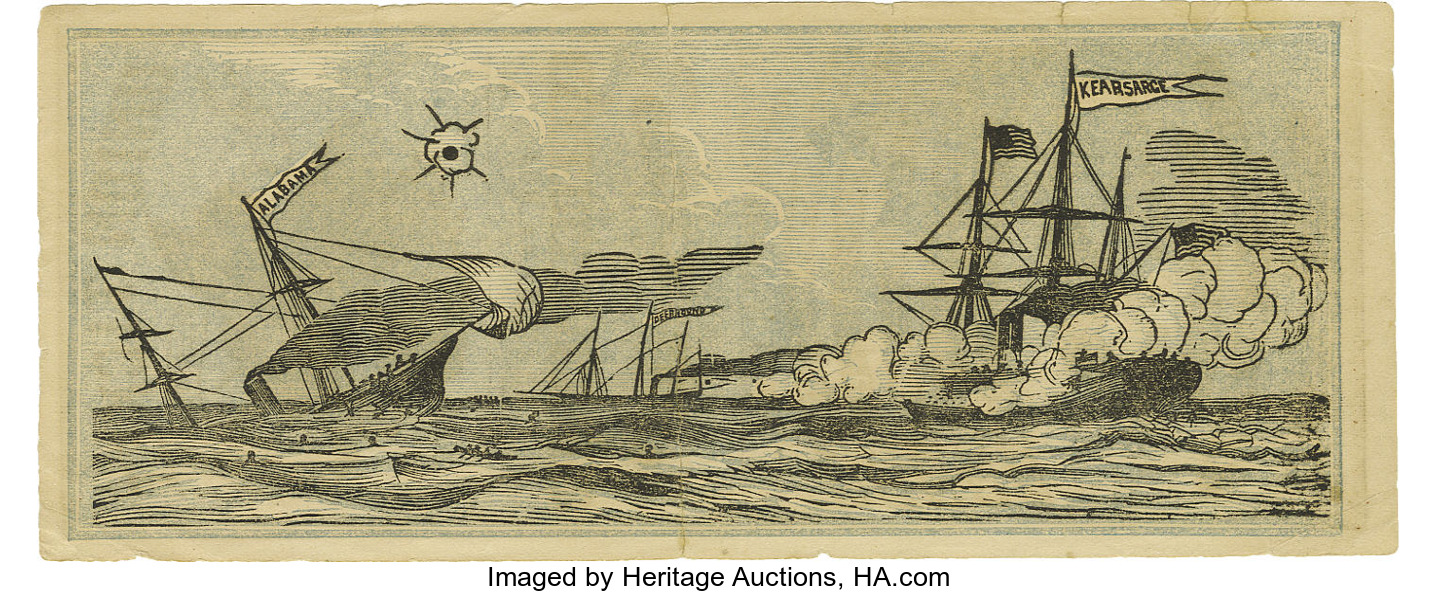

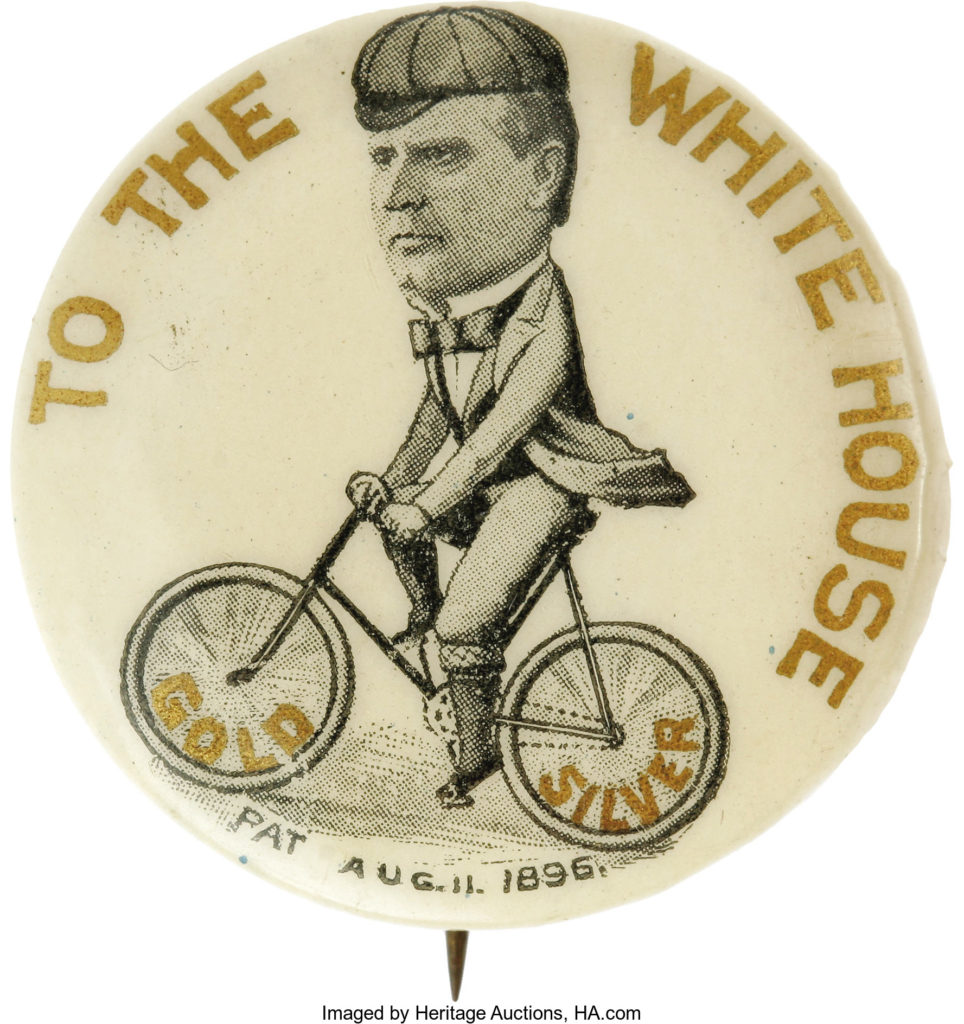

In the United States, another generation of anti-slavery groups are doing the exact opposite: lobbying to have statues and monuments removed, destroyed or relocated to obscure museums to gather dust out of the public eyes. Civil War flags and memorabilia on display were among the first to disappear, followed by Southern generals and others associated with the war. Now, streets and schools are being renamed. Slavery has understandably been the reason for the zeal to erase the past, but it sometimes appears the effort is slowly moving up the food chain.

More prominent names like President Woodrow Wilson have been targeted and for several years Princeton University has been protested because of the way it still honors Wilson, asserting he was a Virginia racist. Last year, Yale removed John C. Calhoun’s name from one of its residential colleges because he was one of the more vocal advocates of slavery, opening the path to the Civil War by supporting states’ rights to decide the slavery issue in South Carolina (which is an unquestionable fact). Dallas finally got around to removing some prominent Robert E. Lee statues, although one of the forklifts broke in the process.

Personally, I don’t object to any of this, especially if it helps to reunite America. So many different things seem to end up dividing us even further and this only weakens the United States (“United we stand, divided we fall”).

However, I hope to still be around if (when?) we erase Thomas Jefferson from the Declaration of Independence and are only left with George Washington and his extensive slavery practices (John Adams did not own slaves and Massachusetts was probably the first state to outlaw it).

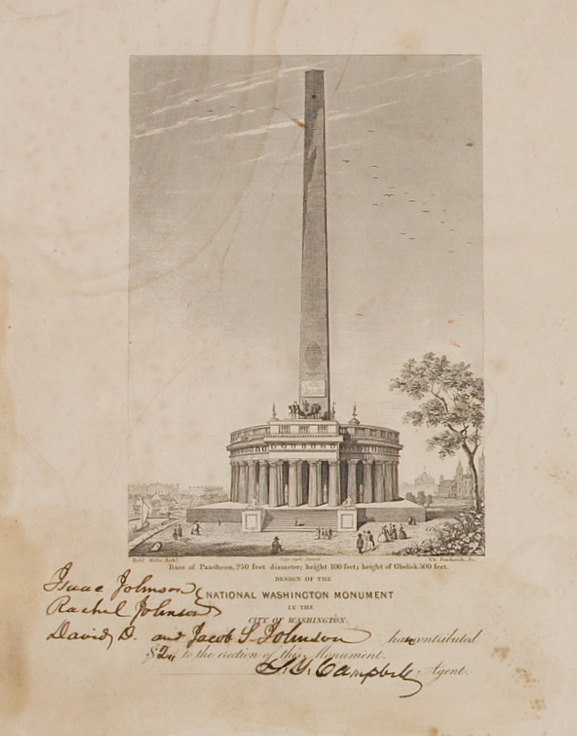

It would seem to be relatively easy to change Mount Vernon or re-Washington, D.C., as the nation’s capital. But the Washington Monument may be an engineering nightmare. The Continental Congress proposed a monument to the Father of Our Country in 1783, even before the treaty conferring American independence was received. It was to honor his role as commander-in-chief during the Revolutionary War. But when Washington became president, he canceled it since he didn’t believe public money should be used for such honors. (If only that ethos was still around.)

But the idea for a monument resurfaced on the centennial of Washington’s birthday in 1832 (Washington died in 1799). A private group, the Washington National Monument Society – headed by Chief Justice John Marshall – was formed to solicit contributions. However, they were not sophisticated fundraisers since they limited gifts to $1 per person a year. (These were obviously very different times.) This restriction was exacerbated by the economic depression that gripped the country in 1832. This resulted in the cornerstone being delayed until July 4, 1848. An obscure congressman by the name of Abraham Lincoln was in the cheering crowd.

Even by the start of the Civil War 13 years later, the unsightly stump was still only 170 feet high, a far cry from the 600 feet originality projected. Mark Twain joined in the chorus of critics: “It has the aspect of a chimney with the top broken off … It is an eyesore to the people. It ought to be either pulled down or built up and finished,” Finally, President Ulysses S. Grant got Congress to appropriate the money and it was started again and ultimately opened in 1888. At the time, it was 555 feet tall and the tallest building in the world … a record that was eclipsed the following year when the Eiffel Tower was completed.

For me, it’s an impressive structure, with its sleek marble silhouette. I’m an admirer of the simplicity of plain, unadorned obelisks, since there are so few of them (only two in Maryland that I’m aware of). I realize others consider it on a par with a stalk of asparagus, but I’m proud to think of George Washington every time I see it.

Even so, if someday someone thinks it should be dismantled as the last symbol of a different period, they will be disappointed when they learn of all the other cities, highways, lakes, mountains and even a state that remain to go. Perhaps we can find a better use for all of that passion, energy and commitment and start rebuilding a crumbling infrastructure so in need of repairs. One can only hope.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].