By Jim O’Neal

At 6 p.m. on Wednesday, Nov. 11, 1987, I was sitting in the Eisenhower Cabin at the Augusta National Golf Club sipping on a Stoli and tonic (there are 10 cabins inside the gates of the course where they play the Masters). It had been a good day, starting with eggs, biscuits and gravy, ham and grits for breakfast and fried chicken for lunch (we took a short break after the front nine).

My playing partner was Charlie Yates, who had played in the first Masters (1934), was Low Amateur five different years, and won the British Amateur Championship in 1938 (he died in 2005 at age 92).

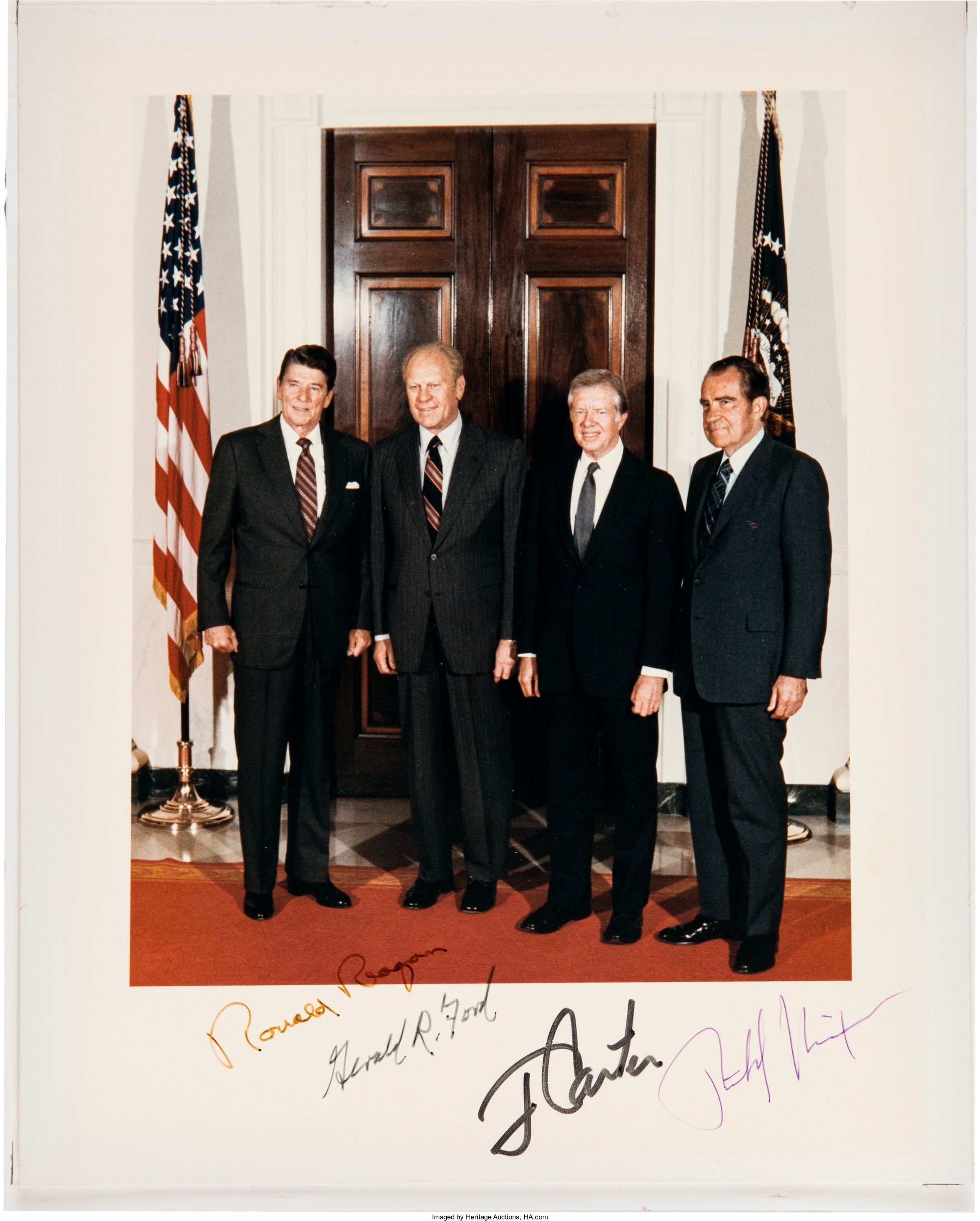

When the 6 p.m. news came on, the big story was the Iran-Contra affair and President Ronald Reagan was scheduled to make a speech from the Oval Office at 8 p.m. I remember commenting that he should just say, “I’m the president and it was my decision due to national security … now who wants to do something about it?” I guess he didn’t … we were having dinner over at the club.

Earlier, on July 7, a 43-year-old ram-rod straight Marine lieutenant colonel had walked into the Caucus Room of the Russell Senate Office Building, raised his right hand for swearing in and proceeded with a performance that would etch his name onto the short list of 20th-century folk heroes. The appearance of Oliver North before the Senate committee charged with investigating the Iran-Contra affair had been anticipated for months … ever since the sensational discovery that the Reagan administration had concocted a bizarre plan to ship American arms to Iran to gain funding for the Contra rebels fighting the Marxist government in Nicaragua.

The plan was a violation of several laws and the trades seemed in direct contradiction of the morally direct philosophy that had been such a large part of Reagan’s appeal. Attorney General Ed Meese and others initially blamed North, an aide on the National Security Council, for directing the operation. But North appeared to be a scapegoat for more powerful Reagan officials, maybe even Reagan himself.

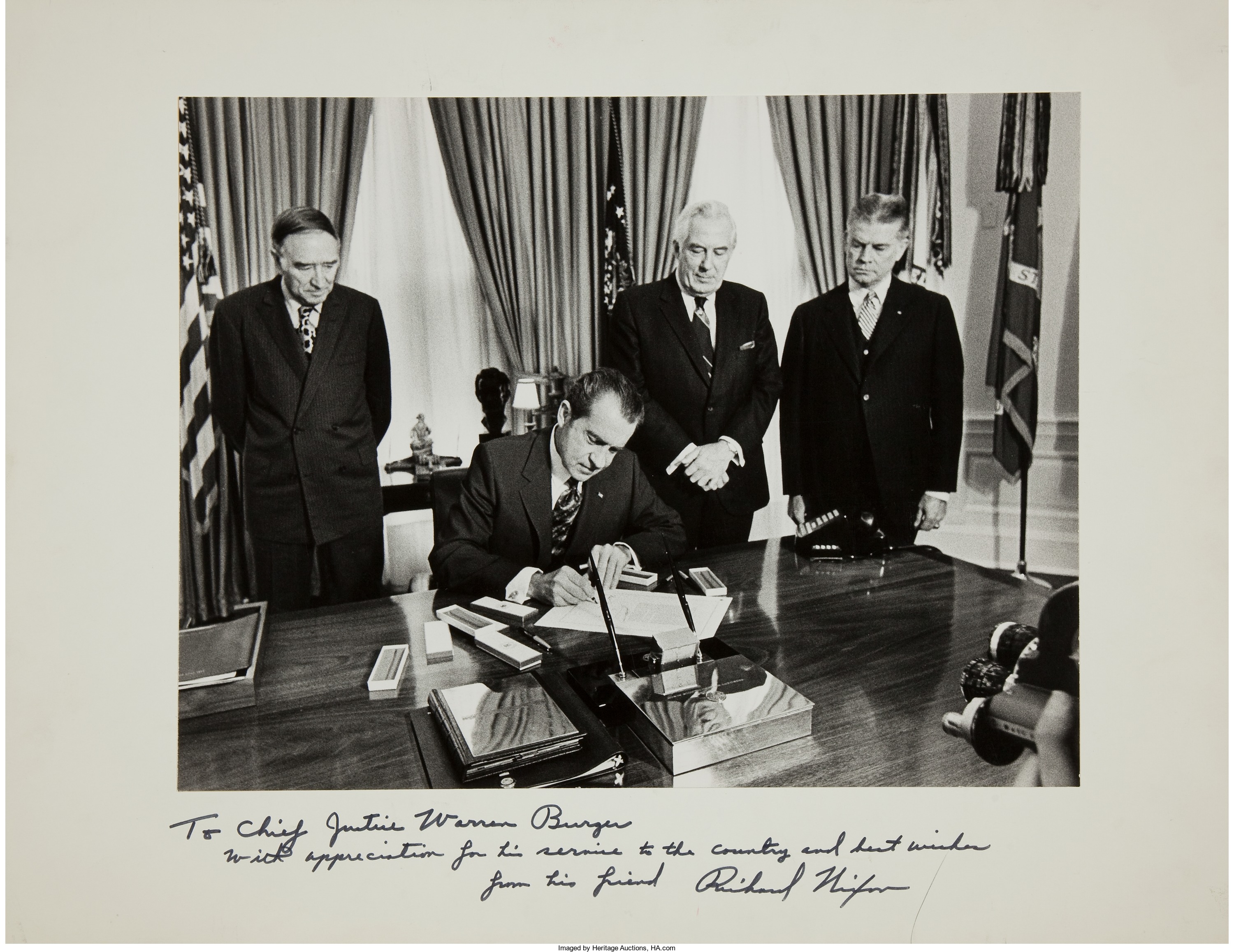

The comparisons to Watergate were tempting and, ultimately, the most commanding comparison came in the central question (again): “What did the president know and when did he know it?” The answer remained unclear despite dozens of people testifying, but that hardly spared Reagan. Either he was a figurehead in a rogue government or an impotent and forgetful leader with a lack of attention to detail.

We spent a long night at the bar with a group of members explaining how the “Iron Mike” golf club testing machine worked, and debating Titleist golf balls versus Wilson Pro Staff.

I think Reagan finally fessed up after blaming his memory … sadly portending things to follow.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is President and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as Chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is President and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as Chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].