By Jim O’Neal

In 1601, William Shakespeare wrote in Twelfth Night: “Some are born great, some achieve greatness and some have greatness thrust upon them.”

In Shakespearean times, greatness was often equated with fame. But, as the Bard pointed out, although people may become famous in a myriad of ways, fame (per se) was predicated most often on the idea of “greatness.” People were famous because they were important in some way.

For most of human history, few individuals in each generation actually achieved great fame. And that fame was usually derived from actions of consequence in politics, war, religion, science or other ways that deeply affected society. However, being famous is not the same as being a celebrity. Many celebrities will never do anything important at all, unless entertainment is loosely interpreted.

Modern celebrity is a relatively recent phenomenon. Before the 20th century, few people were famous without accomplishment. That changed with the advent of national magazines, followed by radio, movies, television and, most recently, the internet and social media. Yet even as the 20th century debuted, many Americans began to look back with a lingering nostalgia for the past. People in the new industrial cities of the Midwest and East began yearning for the fading vision of the Old West. It enveloped even those who had never ventured West of the Mississippi, perhaps as a wistful item to see before it disappeared.

Right on cue was a ready-made version of that romanticized history by one of the 20th century’s first celebrities. William Frederick “Buffalo Bill” Cody (1846-1917) was intimately familiar with the often brutal reality of the 19th century. As a boy in Kansas, he witnessed firsthand his father being attacked and stabbed for his vocal anti-slavery views. At 15, he was one of the short-lived Pony Express riders, followed by stints as a fur trapper, bullwhacker, “Fifty-Niner” (in Colorado), Army scout and, of course, buffalo hunter.

After the Civil War, Cody worked for the Army, sometimes helping to track, fight and even kill American Indians. He worked as a buffalo hunter (technically American bison) on the Great Plains, slaughtering the great beasts to help feed the troops. But he also had a keen eye on fame and a flair for self-promotion. In his late 20s, this led to working as an actor in travelling Wild West road shows.

This new form of entertainment was a live, open-air variety show where crowds were awed by noisy displays of skill involving trick riding, sharp shooting and rope tricks. But the primary crowd-pleasers were large-scale dramatizations of daring Western stories. These were typically battles between “Americans” and Indians in full war paint with galloping horses.

While promoters made wild claims about the authenticity of the battle stories, in general they were greatly fictionalized or, at a minimum, highly exaggerated. Audiences were enthralled by these largely false, heroic re-enactments of the cruel, brutal conquest of American Indians as the United States “tamed” the West. They inspired Cody, then a youngish 33, to publish his memoir, The Life and Adventures of Buffalo Bill.

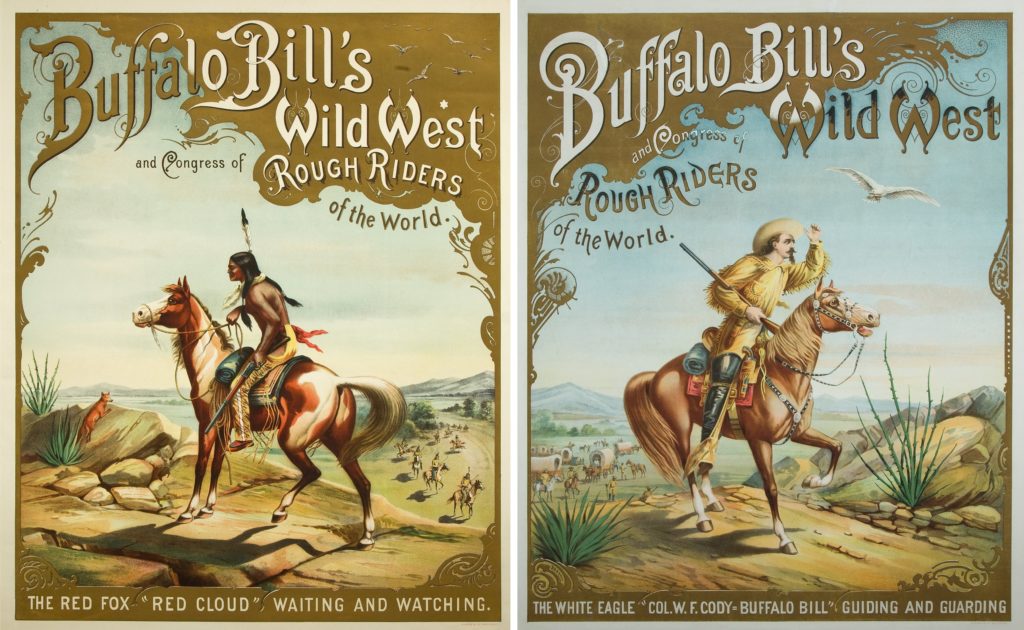

It provided a handy springboard for his own road show in 1883: Buffalo Bill’s Wild West. Earlier, his life and adventures had been sensationalized in a series of dime novels by E.Z.C. Judson (alias Ned Buntline) and his fame gained an international flair as just “Buffalo Bill.” Cody then spent the better part of three decades touring the United States with a large company of entertainers. Among them were American Indian people from the West, which resulted in a somewhat complicated relationship. However, the shows provided them with decent wages and a welcome escape from the grinding poverty of the reservations they eschewed.

Meanwhile, white performers like “Wild Bill” Hickok and Annie Oakley were developing their own celebrity status. Annie regarded Buffalo Bill as “the kindest, simplest, most loyal man I ever knew.” He called her the “Champion Shot of the World.” Unlike much of the highly fictionalized show, Oakley was the real deal. Born Phoebe Ann Mosey in 1860, she learned to shoot as a child to help feed the family. Years later, while competing in a shooting contest, she met her future husband, traveling-show sharpshooter Frank E. Butler (whom she defeated when he missed the last of 25 balls and Annie hit all 25). When the couple joined Buffalo Bill’s extravaganza, Annie took the spotlight and Frank became her manager. They were married for 50 years and he died three weeks before her death.

In one example of her dazzling act, Butler would swing a glass ball at the end of a string, and Annie, with her back turned, sited the moving target and shot it with her gun slung over her shoulder. She was universally admired and Chief Sitting Bull (another star of the show) called her “Miss Sure Shot.”

Buffalo Bill sensed there was a big opportunity in Europe and in 1887 his troupe sailed off to London with 180 horses, 18 buffalo, 97 American Indians and a full-size Western stagecoach. The show was an exceptional success in England, where enormous crowds had gathered for Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee. The queen even attended a performance and reportedly called Annie “a very clever little girl.”

A second trip to Paris in 1889 to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the French Revolution was even more successful. Millions attended the Paris Exposition with Cody’s “Buffalodrum” the clear favorite. The tour was extended to include the Pope and then on to Berlin, where Kaiser Wilhelm reportedly had Annie shoot a cigar out of his mouth. Annie later quipped a fatal miss could have prevented World War I (the young Kaiser played a major role in launching the war). She was such a success that the King of Senegal wanted to buy her for 100,000 Francs.

By 1900, Buffalo Bill was one of the most famous Americans in the world. He had achieved his celebrity by offering people an idealized version of the complicated and tumultuous 19th century American West. Perhaps more than anyone else, Bill, Annie and their troupe of cowboys and Indians created the myth of the Wild West that remains with us today.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].