By Jim O’Neal

The last truly great Civil War book I read was Doris Kearns Goodwin’s Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln (2005). The award-winning book focuses on the 1860 presidential election and how underdog Lincoln was able to secure the Republican nomination against three formidable opponents, and then win the presidency without a single Southern vote (he was not on any Southern ballot).

Then, it deftly explains how President Lincoln was able to recruit all three Republican opponents to serve as key members of his Cabinet: New York Senator William H. Seward (Secretary of State), Ohio Governor Salmon P. Chase (Treasury Secretary), and Missouri’s favorite son Edward Bates (Attorney General). Next was the brilliant way he managed to leverage each man’s strength and weakness into a form of political-enemy synergy.

Steven Spielberg secured the film rights before the book was written and his 2012 movie Lincoln was highly acclaimed. Out of 14 Oscar nominations, Daniel-Day Lewis won for Best Actor. But the movie was really only about the last four months of Lincoln’s life when he maneuvered to get the 14th Amendment approved. Neither the book nor film spends much time on the Confederacy or the underlying circumstances that made the Civil War inevitable.

This is not unusual, since books about Lincoln, his Cabinet and the generals of the war pop up with regularity. Relatively little has been written about the Confederacy per se (i.e. the formal government of the South). The primary focus seems confined to biographies of Robert E. Lee, Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson or the famous battles between the North and South (such as Gettysburg).

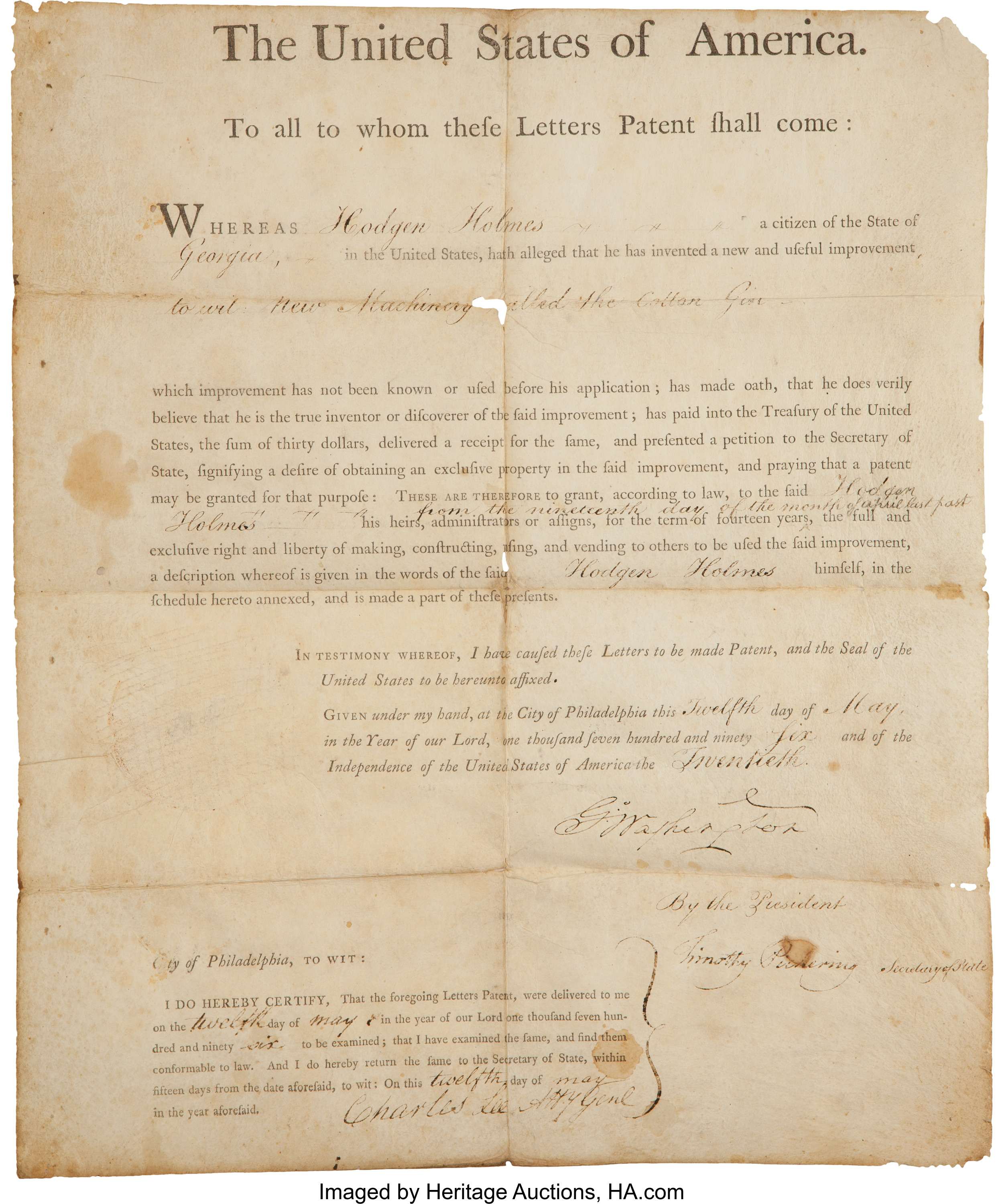

Sure, people might know that Jefferson Davis was president of the CSA or that Alexander H. Stephens was vice president. But these two men were in office the entire war, from April 1861 to May 1865. Perhaps interest in individuals is limited because, as some historians argue, the Confederate States of America represented an entire people’s effort to cling to their past. They feared after the 1860 election that Lincoln and the now-dominant Republicans would simply force them to abandon the practice of slavery. So they naively decided to secede from the Union and start their own country.

They started with seven secessionist slave-holding states and in February 1861 established a new Confederacy in Montgomery, Ala., before Lincoln even took office. After Confederates fired on Fort Sumter in April, four more states seceded and joined the Confederacy (now based in Richmond, Va.). Missouri and Kentucky were later accepted but did not secede. Two seats in the Confederate Congress were given to Southern California.

Organizationally, the Southern government was much like the North. They had a Constitution and a Cabinet with six departments that composed the executive branch. With few exceptions, they replicated their counterparts in the Union. A prominent exception: the Attorney General was elevated to Cabinet status. It grew in importance since the Confederacy had no Supreme Court; the Department of Justice arbitrated any legislation or constitutional disputes.

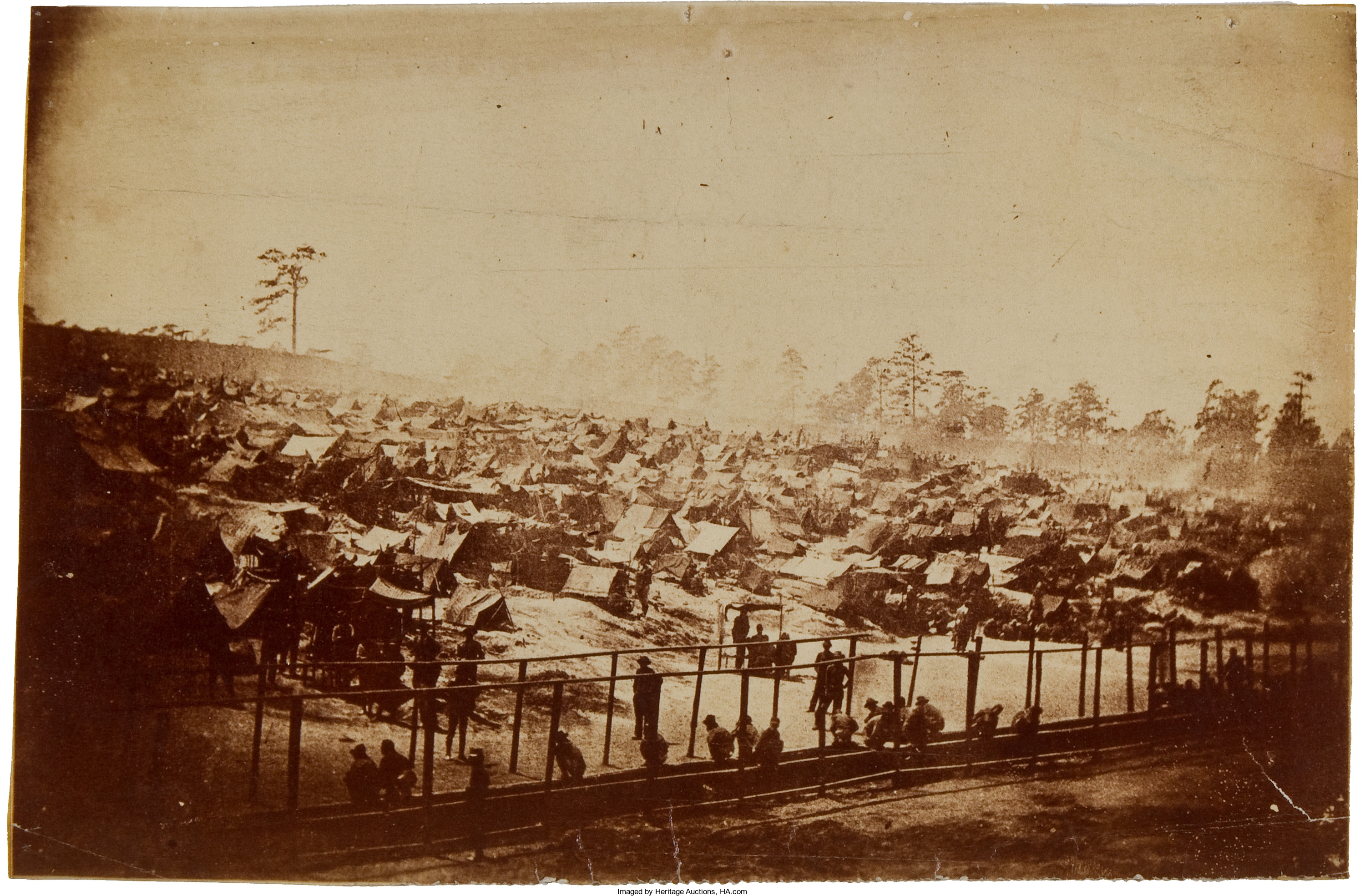

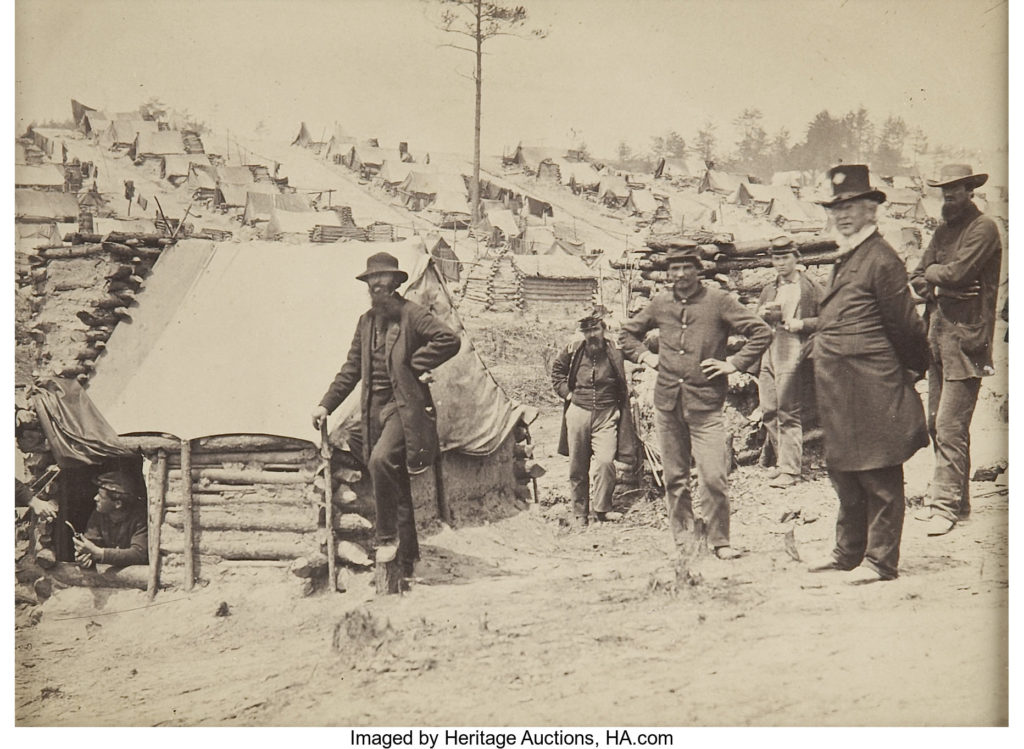

However, most departments discovered their limitations once the War started. The Navy began the war without a single major vessel and soon lost easy access to international sea-lanes from Southern ports. The Treasury and War departments did not have the resources of their Union counterparts, little things like enough money or an army and a non-industrial economy. Here, one must ask: Who were these men and what were they thinking?

Some deep thinkers sincerely believe it was an honest attempt to build a New South with 11 individual states forging a future based on prosperity from land and slaves. After all, only 4 percent to 5 percent had direct involvement with the institution of slavery. The majority considered their way of life inviolate enough to defend it by force of arms. However, despite obvious mismatches from virtually every aspect, that did not deter its political leaders. They assured the Southern people that courage and determination could substitute for limited resources, limited manpower and lack of foreign aid.

The South’s goal of independence was as absolute as the North’s determination to maintain the Union. Hence, the objectives of the opposing governments could be neither compromised nor harmonized. The Civil War would have to be a fight to the finish.

For four long years, against impossible odds, the South persevered and suffered. It accepted honorable defeat and then wrapped itself in nostalgia. The South’s postwar vision of “The Lost Cause” – fighting and surrendering with honor – became a soothing balm for the sores of war.

However, President Jefferson Davis would admit much later, “The simple fact was the people had gone to war without considering the cost.”

Case closed.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].