By Jim O’Neal

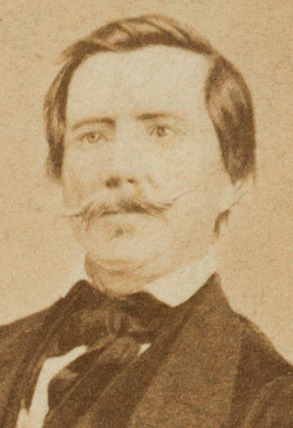

Stephen R. Mallory was born in Trinidad, British West Indies. In 1850, the Florida legislature elected Mallory (1812-1873) to be a U.S. Senator and he was re-elected in 1856. He was appointed to the Senate Committee on Naval Affairs and was unsuccessful in appropriating funds for the development of an ironclad floating battery, a forerunner of armor-clad ships.

In 1858, President Buchanan offered to appoint him Minister to Spain, but he declined. Although a strong supporter of the South, he opposed secession. Nevertheless, he resigned on Jan. 21, 1861, after Florida left the Union.

Jefferson Davis quickly named Mallory head of the Confederate Naval Department on Feb. 25, 1861. He had not sought the office and was not even aware of the nomination. One reason for his appointment was that he came from Florida, which had been given a prominent Cabinet post as a reward for its early date of secession. However, the Florida delegation opposed his nomination over a misunderstanding about his actions involving Fort Pickens, but he was finally confirmed as Confederate States Secretary of the Navy on March 4.

Mallory’s department at the start of the war consisted of 12 smallish ships and 300 officers who had left the Union Navy. In May 1863, Mallory was able to persuade the Confederate Congress to create a Provisional Navy and this gave him the opportunity to recruit and train more sailors. Many of these men eagerly transferred from the Army, despite significant opposition from a series of Secretaries of War.

When the Civil War got under way, Union anchorages were crammed with wooden warships mostly obsolete. Unable to compete with the U.S. Navy on numerical terms, the South saw an opportunity to seize a technological edge to negate the advantage in timber and guns. Since Mallory had to purchase ships built abroad, he emphasized the building of several powerful ironclads, along with gunboats and other vessels.

Mallory also played an active role in the development and use of torpedoes (mines). These devices became one of the most successful aspects of the navy throughout the war. Confederate minefields helped keep the Union Navy from entering Charleston Harbor and delayed the attack on Mobile Bay. By the end of the war, torpedoes had sunk or damaged 43 enemy vessels, including four monitors. These devices destroyed more Federal warships than the entire fleet of Confederate gunboats.

Mallory also championed the development and employment of torpedo boats and submarines. One of the first submarines was Pioneer, which was built at New Orleans, but scuttled when the city fell, never having an opportunity to attack the enemy. The H.L. Hunley became the first submarine in history to attack and sink an enemy, the ocean steam sloop USS Housatonic.

But it was the showdown on March 8-9, 1862, between the CSS Virginia (a rebuilt frigate that never shook her original name, Merrimack) and the USS Monitor that generated the most news on both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line. The Battle of Hampton Roads was the most important naval battle of the Civil War and was an effort of the Confederacy to break a Union blockade that had cut off international trade from Virginia’s largest cities of Norfolk and Richmond.

It was the first combat meeting of the famous ironclad ships and they dueled for four hours with neither inflicting damage on the other. Despite this strategic draw, The New York Times ran 17 articles on the battle. Harper’s Weekly thrilled its readers with an action-packed cover story, while Currier & Ives issued three different lithograph versions titled “Terrific Combat.”

Of interest was that the commander of the CSS Virginia, Franklin Buchanan, an officer in the U.S. Navy, became the only full Admiral in the Confederate Navy. Earlier in 1845, at the request of the Navy, he submitted plans for a naval school that became the United States Naval Academy and Buchanan became the first superintendent.

He resigned his commission in 1861 in anticipation of Maryland seceding. When that didn’t happen, he tried to recall his resignation but Gideon Welles – President Lincoln’s Secretary of Navy – refused, citing “half-hearted patriots.”

Stephen Mallory spent several years in prison and then returned to Pensacola and his law practice. He and Confederate States Postmaster General John Reagan were the only two men who remained in their Cabinet positions throughout the entire war.

Complicated times.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].