By Jim O’Neal

Some presidential tidbits:

Three sets of presidents defeated each other:

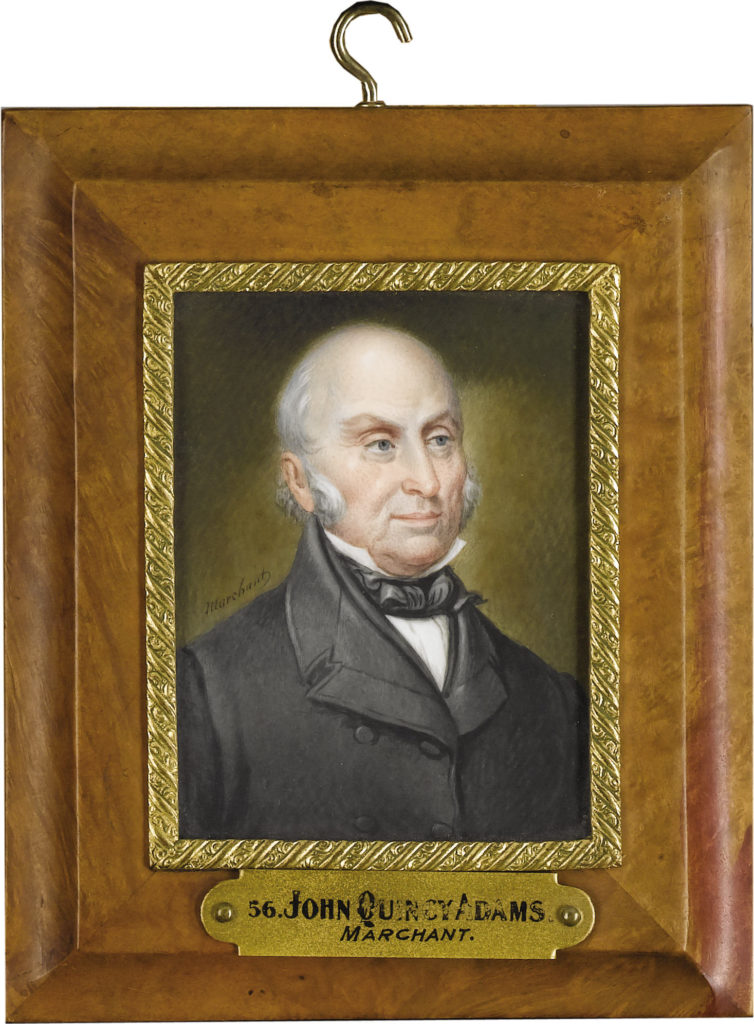

► John Quincy Adams defeated Andrew Jackson in 1824; Jackson defeated Adams in 1828.

► Martin Van Buren defeated William H. Harrison in 1836; Harrison defeated Van Buren in 1840.

► Benjamin Harrison defeated Grover Cleveland in 1888; Cleveland defeated Harrison in 1892.

So much for the power of incumbency.

♦

John Quincy Adams and wife Louisa were the first presidential couple to be married 50-plus years. She remains the only First Lady born outside the United States (London) and the first to write an autobiography, “Adventures of a Nobody.” When she died in 1852, both houses of Congress adjourned in mourning (a first for a woman).

While in the Senate, John was “Professor of Logic” at Brown University and professor of rhetoric and oratory at Harvard.

♦

Herbert Clark Hoover was the last president whose term of office ended on March 4 (1933).

He married Lou Henry Hoover (the first woman to get a degree in geology at Stanford), and when they were in the White House, they conversed in Chinese whenever they wanted privacy.

♦

Our 10th president, John Tyler, only served 31 days as VP (a record) before becoming president after William Henry Harrison’s death.

His wife Letitia was the first to die while in the White House. When John re-married, several of his children were older than second wife Julia.

Tyler’s death was the only one not officially recognized in Washington, D.C., because of his allegiance to the Confederacy. His coffin was draped with a Confederate flag.

♦

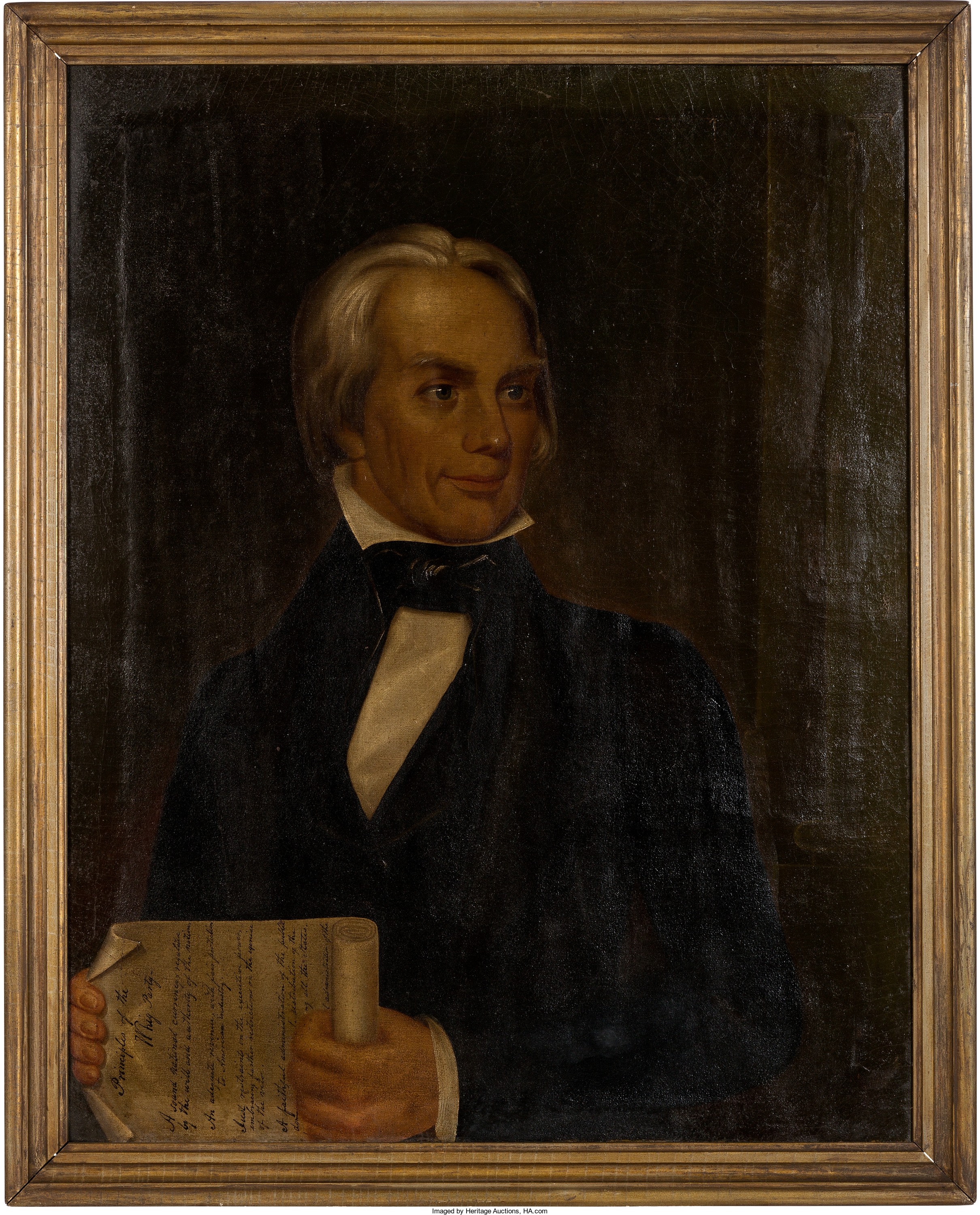

Our sixth president, James Monroe, was the first senator elected president. His VP for a full eight years, Daniel D. Tompkins (the “D” stood for nothing), was an alcoholic who several times presided over the Senate while drunk. He died 99 days after leaving office (a post vice-presidency record).

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].