By Jim O’Neal

The U.S. Constitution is generally considered the most revered document in world history. John Adams described it as “the greatest single effort of national declaration that the world had ever seen.” It was a seminal event in the history of human liberty. While containing remarkable concepts — “All men are created equal” … “Endowed with certain unalienable rights” … “Consent of the governed” (instead of the will of the majority) — the founders proved to be incapable of reconciling the practice of slavery with these lofty ambitions.

In order to gain consensus, they deftly employed what has become known colloquially as “Kick the can.” International slave–trading was banned in the United States, but Congress was denied the right to eliminate slavery per se for 20 years (1808). The assumption (hope) was that slavery would just naturally phase out without the need for formal legislation. Then there was the obvious contradiction between men being born equal while slavery was allowed to continue. The explanation was a tortured rationale that “equal” was meant to mean “under the law” and not racial equality.

We now know that rather than phasing out, slavery flourished as Southern agrarian economies became even more dependent on slave labor and geographical expansion added to the importance of the issue. So the dispute took on new dimensions as each new state entered the Union. Was it to be free or slave? The answer was up to a divided Congress to decide. In an effort to maintain harmony, Congress was forced to negotiate a series of compromises, first in 1820 and again in 1850 and 1854. Rather than continue to battle in Congress, Southern slave states turned to secession from the Union when it was clear that they weren’t strong enough to rely on nullification alone.

What the Northern states needed desperately was a president with the will-power to keep the Union intact … with or without slavery.

His name was Abraham Lincoln, a little–known lawyer from Illinois. Today, most Americans know the major details of the life of the man who would become the 16th president of the United States. His humble upbringing in a pioneer family, his rise from lawyer to state legislator and presidential candidate, his wit and intelligence, his growth as a statesman to become the virtual conscience of the nation during the bloodiest rift in its history. Far fewer are familiar with the decisions and qualities which combined to create the most extraordinary figure in our political history.

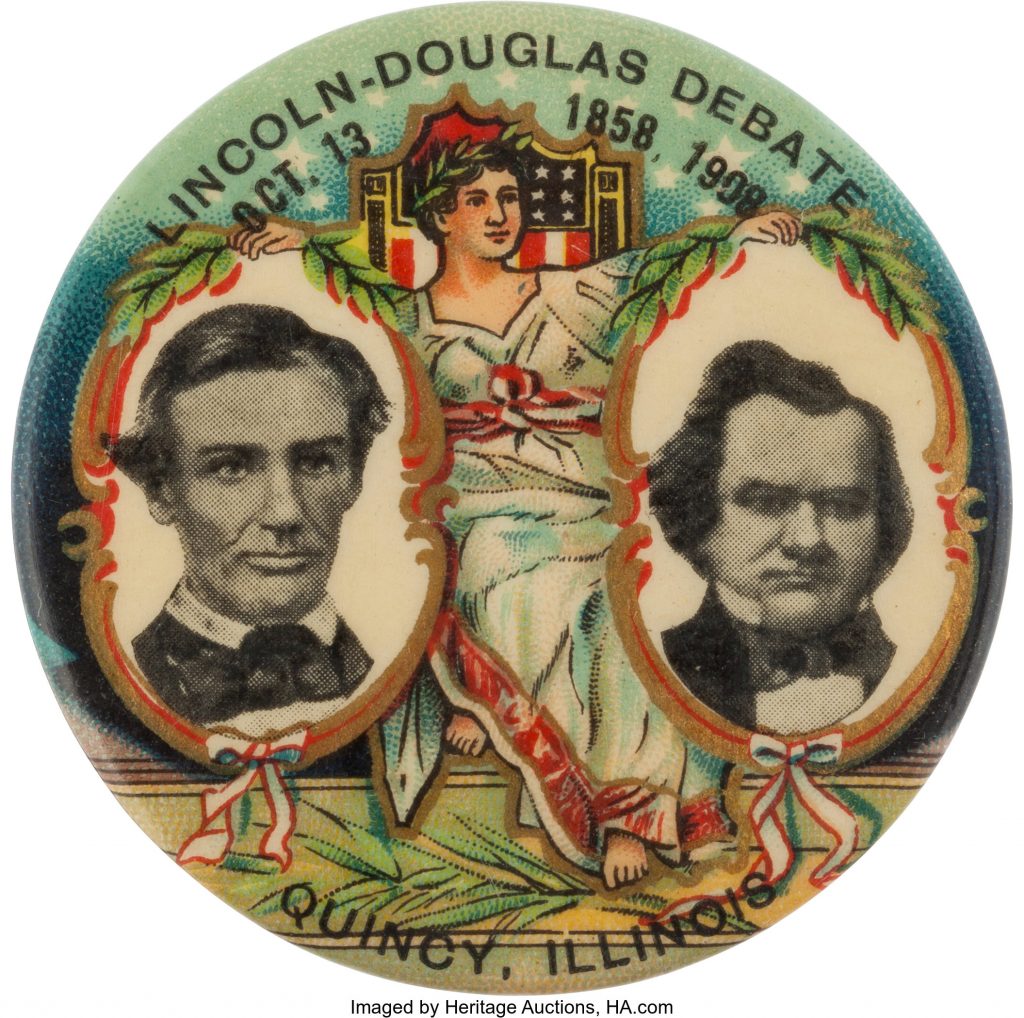

In 1858, he challenged Illinois Senator Stephen Douglas in his bid for re-election. Although Lincoln lost, he developed a national prominence when they engaged in a series of high–profile debates, primarily over slavery. Lincoln was eloquent in his attacks from a moral-ethical standpoint, while Douglas was firm in his belief in states’ rights to decide important issues. Then came the presidential election of 1860, with the country poised for war, and the outcome would be the determining factor. It was during the hotly contested campaign that the Democratic nominee Douglas would perform an epic act of “Nation over Party.”

Two years later, Douglas sensed that Lincoln would win the presidency as Pennsylvania, Ohio and Indiana swung to the Republicans. Douglas famously declared “Mr. Lincoln is the next president. We must try to save the Union. I will go South!” Despite a valiant effort consisting of speeches to dissuade the South, it was too late. During the 16 weeks between Lincoln’s election in 1860 and the March 4, 1861, inauguration, seven states had seceded from the Union and formed the Confederate States of America.

On June 3, 1861, the first skirmish of the war on land occurred in (West) Virginia. It was called the Battle of Philippi and it was a Union victory. A minor affair that lasted 20 minutes with a few fatalities, the Union nevertheless celebrated it with fanfare. Ironically, Senator Douglas died on the same day at age 48. Three weeks later, the Civil War exploded at the Battle of Bull Run and would continue for four long bloody years.

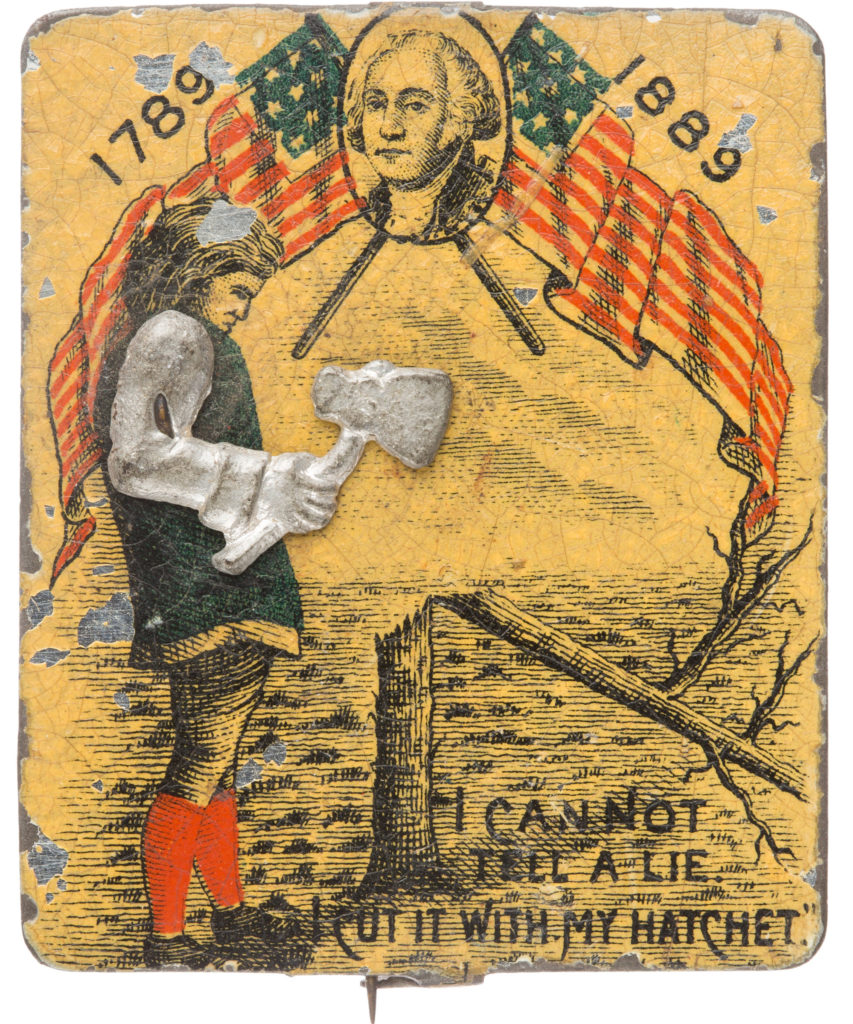

One has to wonder if this could have been avoided if our remarkable founders had been more prescient about the slavery issue and ended it with the adoption of the Bill of Rights. Or were those early Virginia presidents — Washington, Jefferson, Madison and Monroe — too jaded or selfish to make the personal sacrifice?

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].