By Jim O’Neal

As the departing carriages occupied by Andrew Johnson and his party passed out of the White House gate, the roar of voices heralded the approach of the incoming president’s inaugural parade.

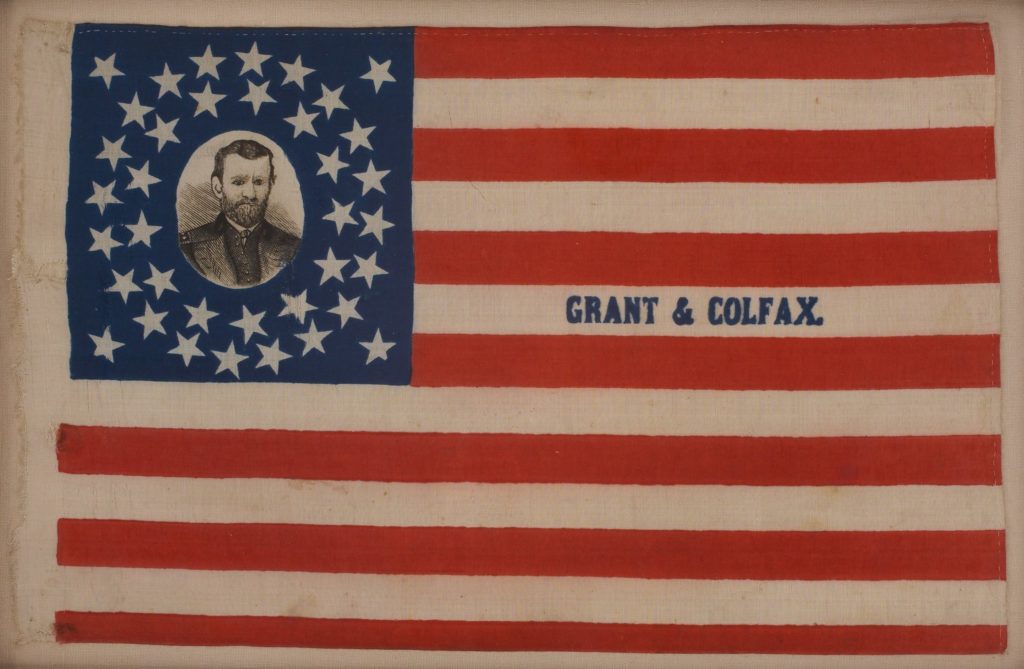

It traversed 15th Street and turned west on Pennsylvania Avenue, where the vanguard of soldiers came into view. Ulysses S. Grant and several others rode in the first carriage, an open barouche. At 1 p.m., the procession stopped and Grant’s carriage rolled through the gates leaving everyone else in the street.

At 46, the idol of the nation assumed the position of commander-in-chief in 1869. There are few important events in the affairs of men brought about by their own choice, Grant observed philosophically in his memoirs. A mere 10 years earlier, he had been an obscure citizen of Galena, Ill., an Army veteran retired early and a businessman struggling to support a young family. He had been considered a failure, but the Civil War had dramatically bettered his life.

Grant had a simple and uncomplicated view of himself as the administrative officer of the nation, drawing a strong analogy between his role as president and his former one as commanding general of the U.S. Army. He believed that the people’s will was expressed through Congress and that the job of president was to manage the machinery of government and obey Congress. His acknowledgment of the superior authority of the legislative branch was appreciated by a people exhausted by the long duel between Andrew Johnson and Congress.

Grant would call the White House home for eight years, the longest time he had lived anywhere. He would be the first two-term president since Andrew Jackson (10 different men had held the job after “Old Hickory” departed). Where those before him sought to achieve their objectives through their conduct as president, Grant’s motivation was neither intellectual nor imaginative, with only a touch of originality. He simply used his prestige to bring stability to the nation by representing the popular image of the “good life” in an era that would be called the Gilded Age.

However, his military background was not enough to equip him for the complexities of governing a large and swiftly growing nation, and historians have largely judged him a failure as president. The common-sense approach that worked so well on the battlefield proved naïve in a world of shrewd politicians and intrigue that permitted shady self-dealing and the aura of corruption.

One thing is certain. He was one hell of a general and knew exactly how to win wars, irrespective of the carnage and loss of life involved. He certainly deserves a lot of credit for ensuring Abraham Lincoln’s legacy.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is President and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as Chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is President and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as Chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].