By Jim O’Neal

The White House was burned to a shell. The previous evening, British soldiers had found the president’s house abandoned and they feasted on the dinner and wine left there untouched due to the hasty exit of Dolley Madison and the entire staff. The date was Aug. 24, 1814, and the War of 1812 came directly to the young country’s capital. There was little doubt about the enemy’s intentions. Public buildings would be destroyed in retribution for the burning of both the legislature and governor’s residence in York (now Toronto), the capital of Upper Canada.

Someone (other than the First Lady) had rescued the Gilbert Stuart painting of George Washington by trimming it from its heavy frame. Executive papers and personal effects, along with silverware, were hurriedly spirited away by carriage for safekeeping. A torrential rain had mercifully helped minimize the damage.

Three days after the British departed, the Madisons returned to the ruins. The torching of the president’s house had mortified the populace, and political enemies accused Madison of cowardice for fleeing days before the incident. Even the press piled on, asserting that Dolley could have saved more, or worse, that the president could have prevented the entire affair. There was malicious gossip that this might finally reduce the excessive social entertaining of the First Lady.

Fortuitously, refuse from the fire had fallen gracefully within the stone walls of the White House and virtually no debris was scattered on the surrounding grounds. The city superintendent commissioned an assessment of all public buildings and the consensus was the White House was damaged more than the Capitol or other executive buildings. Since the blackened shells were shameful symbols of defeat, a debate arose over whether the federal city should be rebuilt. New buildings in a different location could provide an opportunity for a fresh start.

Cincinnati was mentioned as a perfect candidate since it was more central to the country’s westward expansion; the Ohio River and new steamboat connections to St. Louis and New Orleans would facilitate commerce. It would also minimize the need to contend with crossing the mountains, and the re-centering rationale was similar to the arguments used to support the earlier move from Philadelphia to Virginia. Fate intervened just in time with news of victory and the Treaty of Ghent, which ended the War of 1812 between the United States and the United Kingdom.

Congress hastily ratified an appropriation of $500,000 to fund the restoration of all damaged buildings. Jubilant backers of the city implied promises of more money as needed, knowing that once construction was under way, Congress would have no other option than to continue with the restoration. The capital had been saved and that was all that was important.

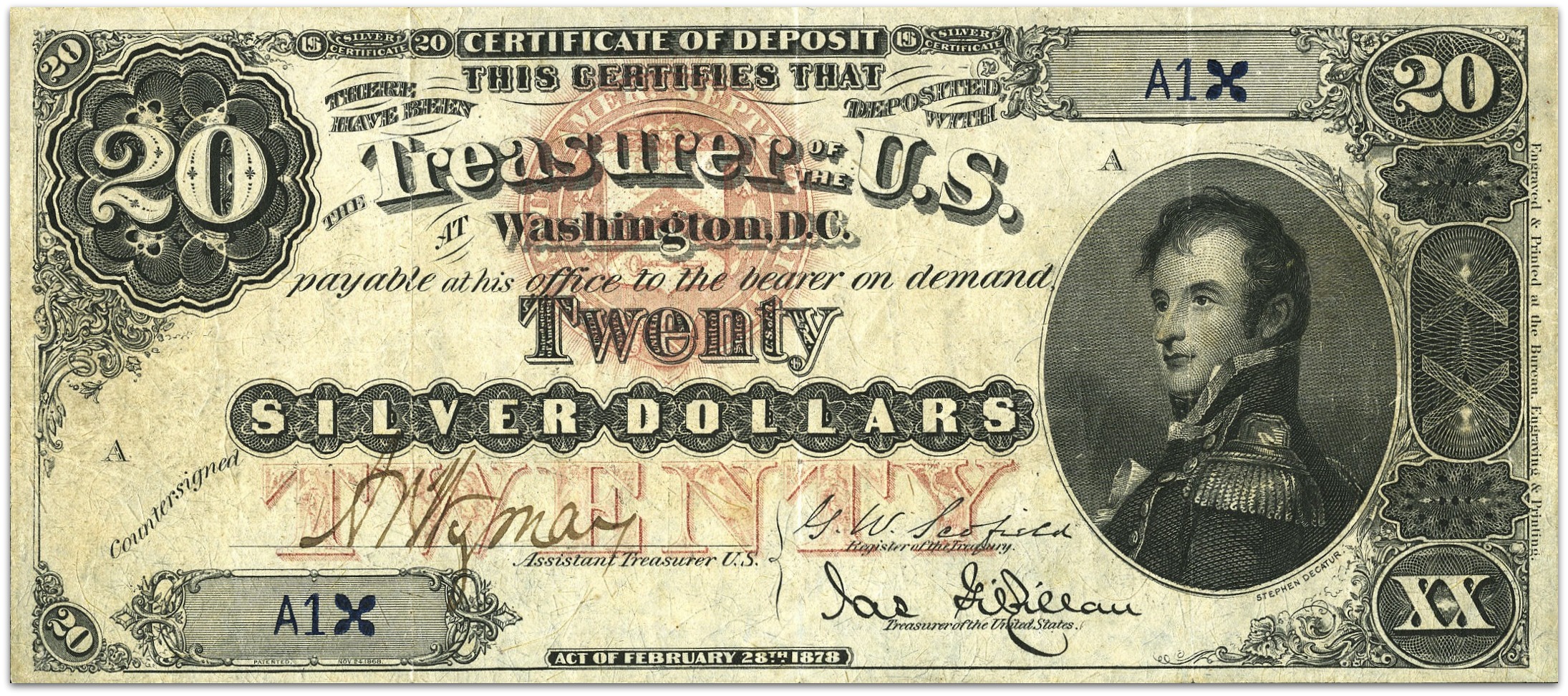

A few months earlier in September, the formidable British Navy attacked Fort McHenry in Baltimore. The fort’s soldiers were able to withstand 25 hours of bombardment. The next day, they hoisted an enormous American flag, which provided the inspiration of a poem by Francis Scott Key – The Star-Spangled Banner, which became an instant hit and in 1931 became the national anthem of the United States. British forces withdrew from Chesapeake Bay and organized their forces for a campaign against New Orleans. This strategic location would provide access to the Mississippi River and the entire western part of the United States. They still hadn’t abandoned their ambition of establishing a British North America.

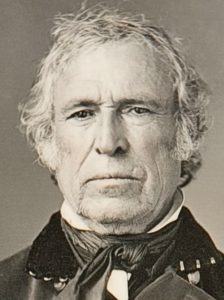

Colonel Andrew Jackson was 45 years old when the War of 1812 started – semiretired on his 640-acre plantation the Hermitage – and still with a burning ambition to get involved. His prayers were answered with the assignment to assume command of New Orleans. His ragtag group of free blacks, pirates (including Jean Lafitte) and loyal Tennessee Volunteers cleverly defeated the British. General Jackson was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal and would become a two-term president in 1828.

In a slight twist, the victory at New Orleans occurred a few weeks after the British had already signed the Treaty of Ghent. However, Jackson’s role in the war was absolutely critical to the future expansion of the country. Not only did he spare an almost certain loss of territory in the Southwest, but he also cleared the air over the status of the Gulf Coast. Great Britain did not recognize any American claims about lands included in the Louisiana Purchase. They disputed – correctly – the legality of the treaty. France had no legal right to sell it to the United States since the 1800 Treaty of San Ildefonso between Spain and France specifically stated that France would not sell without offering to return it to Spain. This meant that none of the lower Mississippi or any of the Gulf Coast belonged to the United States.

Their claims were blithely ignored and the Treaty of Ghent was silent on the entire issue. It has been said that there were no winners or losers in the little War of 1812 … except for American Indians. The United States signed 15 different treaties guaranteeing their lands and then proceeded to break every one of them.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].