By Jim O’Neal

At some point when John Wilkes Booth was planning to assassinate President Abraham Lincoln, he must have decided that it would be more impactful to decapitate the primary leadership of the North and expand the hit list to include Vice President Andrew Johnson, Secretary of State William Seward and, perhaps, even General Ulysses S. Grant. After all, they were in Washington, D.C., and unprotected. It was a desperate move, but it might bolster the morale of the South. In the end, it failed because of a series of unrelated circumstances.

General Grant had declined the invitation of the president to attend a theater show because there was an eagerness to return home and resume normal life. However, that would still leave Secretary Seward, who was at home recuperating from a serious carriage accident that required medical attention. Vice President Johnson had already booked a room that night in the Kirkwood Hotel. Both men would be relatively easy targets for Booth’s co-conspirators.

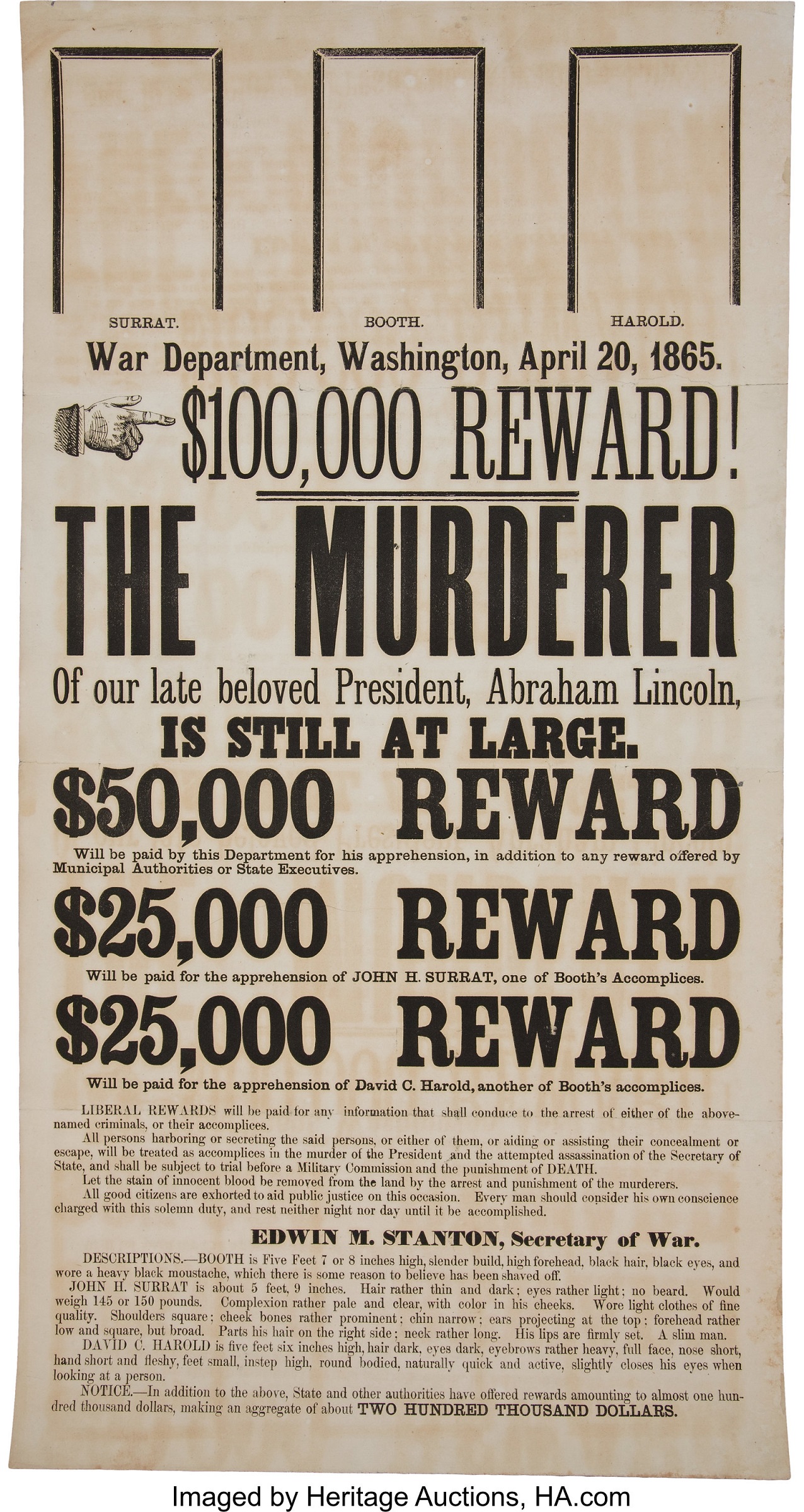

Lewis Powell, the man assigned to kill Seward, had a clever plan to act like a delivery boy bringing medicine, enter the house and shoot the bedridden Seward. He did manage to stab Seward in the throat, but a metal splint on his jaw deflected most of the blows. Powell ran from the house, was easily captured and later hanged. The other conspirator, George Atzerodt, managed to book a room at the Kirkwood Hotel, but started drinking at the hotel bar, lost his nerve and fled. He was also captured and hanged. That only left Lincoln, and Booth shot him in the theater as he watched “Our American Cousin” with Mary by his side.

The date was April 14, 1865. The location was Ford’s Theatre.

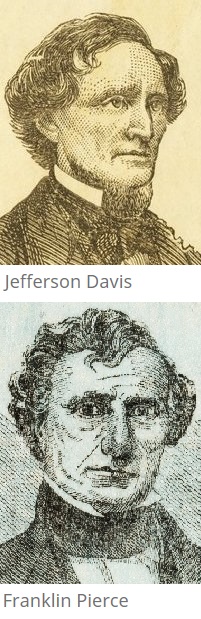

Lincoln had won the 1860 presidential election by defeating three opponents. One was Senator Stephen A. Douglas, a Democrat from Kentucky who had helped Lincoln gain national prominence through a series of high-profile debates regarding slavery. (Douglas, coincidentally, died just two months after Lincoln was inaugurated). A second Democratic opponent was John C. Breckinridge – the incumbent vice president for James Buchanan. The third – John Bell – was the Tennessee Senator who ran as the candidate for the Constitutional Union Party, a group that was neutral on slavery but adamant that the Constitution be upheld. Lincoln’s 180 electoral votes were more than the other three combined.

Now it was four years later and President Lincoln was struggling to barely hang on. In June 1864, the prospects for the Union Army were equally dim. General Grant was bogged down in Virginia, General William Tecumseh Sherman was stalled before Atlanta and heavy casualties were shocking people back home. There was even talk about suspending or postponing the election due to the national crisis. But, as President Lincoln pointed out, “We cannot have free government without elections. If this rebellion forces us to forego a national election, it will appear we’re conquered and ruin us.”

We all now know that the 1864 election did go ahead as planned. It was the first time any nation held a general election during a major domestic war.

However, President Lincoln took a pounding in the press. Horace Greeley, founder-editor of the New-York Tribune, claimed “Mr. Lincoln is already beaten!” The influential James Gordon Bennett, founder-publisher of the New York Herald, was more direct: “Lincoln is a joke!” Some wanted to run Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase and some were clamoring for General Grant. Even Thurlow Weed, Lincoln’s advisor, told him his re-election was hopeless.

Just when it seemed that Lincoln had reconciled himself to defeat, military actions started to slowly improve. Admiral David Farragut (who was the first rear admiral, first vice admiral and first full admiral in the U.S. Navy) won a great victory at the Battle of Mobile Bay (admonishing his men to “Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead”). General Sherman took Atlanta and began his famous “March to the Sea,” which culminated in the burning of Charleston, S.C., where the war had begun. Meanwhile, General Philip Sheridan was routing Southern troops in the valleys of Virginia and then devastating the surrounding areas.

Virtually all of Lincoln’s critics were muffled by these turns of events.

Abraham Lincoln and Andrew Johnson won the 1864 election and the Civil War in 1865. But, the country’s troubles were not over. After Lincoln was assassinated, Vice President Johnson became president and was unable to work with the Republican Congress, which had devised a trap to impeach him. He was acquitted, but lost any hope for governing. He went home a chastened man.

In 1875, he did manage to get re-elected to the U.S. Senate … the only man to do so (up to 2020).

John Wilkes Booth did much more damage than just assassinating a president. By killing Lincoln, he eliminated possibly the only man who could have restored harmony, implemented reconstruction and unified us as our founding documents intended.

Nearly 160 years later, we are still waiting for another messiah.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

In 1819, the United States was a divided nation with 11 states that permitted slavery and an equal number that did not. When Missouri applied for admission to join the Union as a slave state, tensions escalated dramatically since this would upset the delicate balance. It would also set a precedent by establishing the principle that Congress could make laws regarding slavery, a right many believed was reserved for the states.

In 1819, the United States was a divided nation with 11 states that permitted slavery and an equal number that did not. When Missouri applied for admission to join the Union as a slave state, tensions escalated dramatically since this would upset the delicate balance. It would also set a precedent by establishing the principle that Congress could make laws regarding slavery, a right many believed was reserved for the states.