By Jim O’Neal

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (Feb. 2, 1848) was a remarkable document. Primarily it was intended to officially end the Mexican-American War (1846-48). After being ratified by both countries, it was proclaimed on July 5, 1848. The war had started in April 1846 after the U.S. Congress overwhelmingly voted to support President James Knox Polk’s recommendation. For too many years, there had been a distracting dispute over the Republic of Texas and Polk had finally decided to elevate the issue in his hierarchy of priorities. He had committed to serving a single four-year term as president and was determined to resolve this issue in the limited time available.

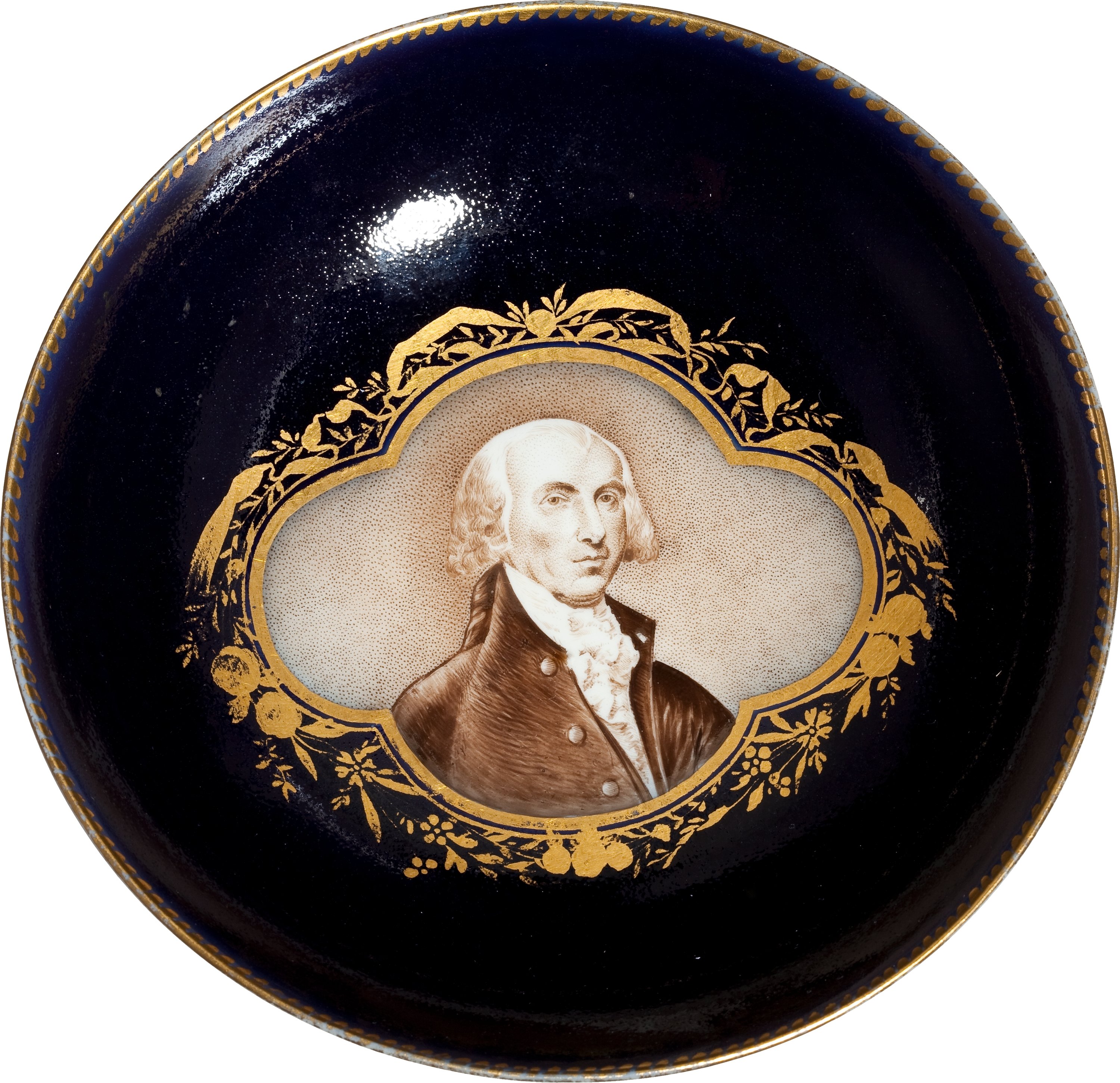

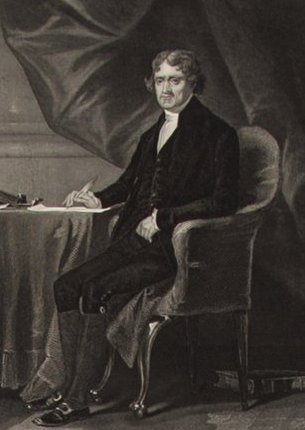

The United States may have already had a legitimate claim on Texas, depending on how the legal boundary of the 1803 Louisiana Purchase from France was imagined. Some claimed that Texas was included (in toto) in the vast territory the United States had acquired under President Jefferson. Precisely what had been purchased was not clear since the wording of the agreement was vague and did not specify exact boundaries. Negotiations had intentionally avoided this level of detail in a rush to complete the deal.

Earlier, before the establishment of fixed boundaries, a Constitutional issue had questioned whether a formal amendment was required since the Constitution did not contemplate actions of this nature. In the end, it was decided to simply approve the purchase using a Senate-approved treaty and the vote was 24-7. It actually took until 1819 to resolve the boundaries and the fact that there were now 30,000 American settlers in Texas made it a rather moot point. However, military action was required to resolve the issue permanently.

There had been a chance to annex Texas in 1836 after the former province won its independence from Mexico, but the possibility of a war with Mexico delayed any action. However, in 1844, President John Tyler initiated negotiations with the new Republic of Texas and a Treaty of Annexation was agreed to. The U.S. Congress soundly rejected the treaty ostensibly because of the war issue, but really because admitting Texas to the Union would disturb the delicate balance of “free states-slave states.” Texas was firmly a slave state and would later secede from the Union and join the Confederacy during the Civil War.

John Tyler was elected the 10th vice president in 1840 on a ticket topped by William Henry Harrison, a military man born in 1773 and the last president born as a British subject in the 13 Colonies. Harrison died 31 days after being inaugurated, thus becoming the first president to die in office. After a brief debate, since the Constitution didn’t include any rules on presidential secession, Vice President Tyler became the 10th president. He holds the dubious distinction of serving longer than any president in U.S. history not elected to the office (four years minus 31 days).

However, he lost support for re-election in 1844 and on Aug. 20 dropped out of the race. In return, President-elect James Knox Polk agreed to support the Texas annexation. Lame-duck President Tyler managed to get a joint-resolution of annexation approved on March 1, 1845 … just three days before Polk’s inauguration. Texas was admitted to the Union on Feb. 19, 1846.

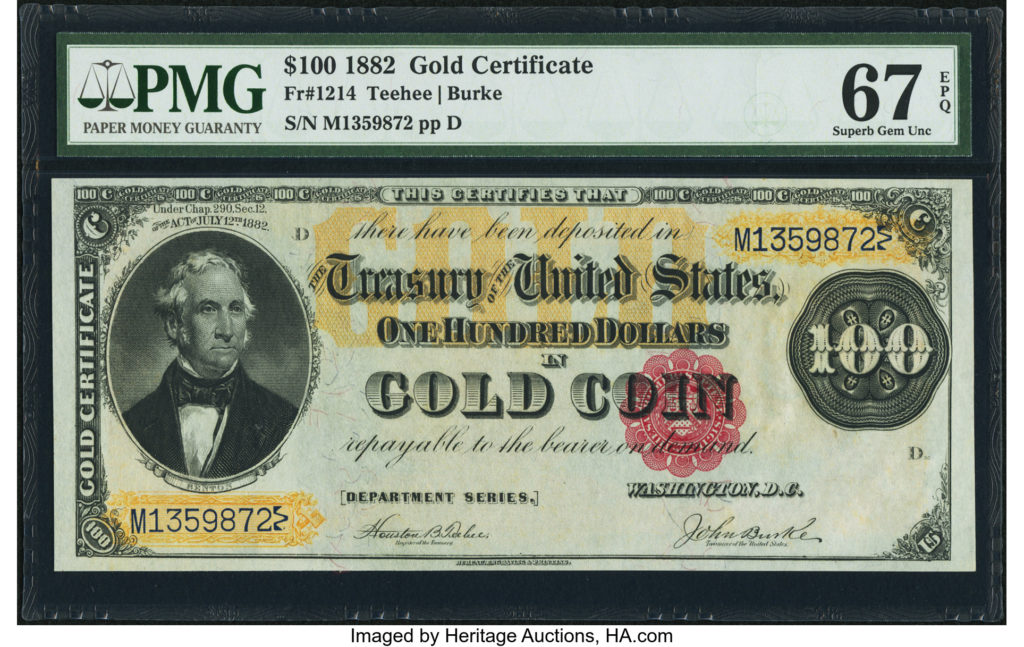

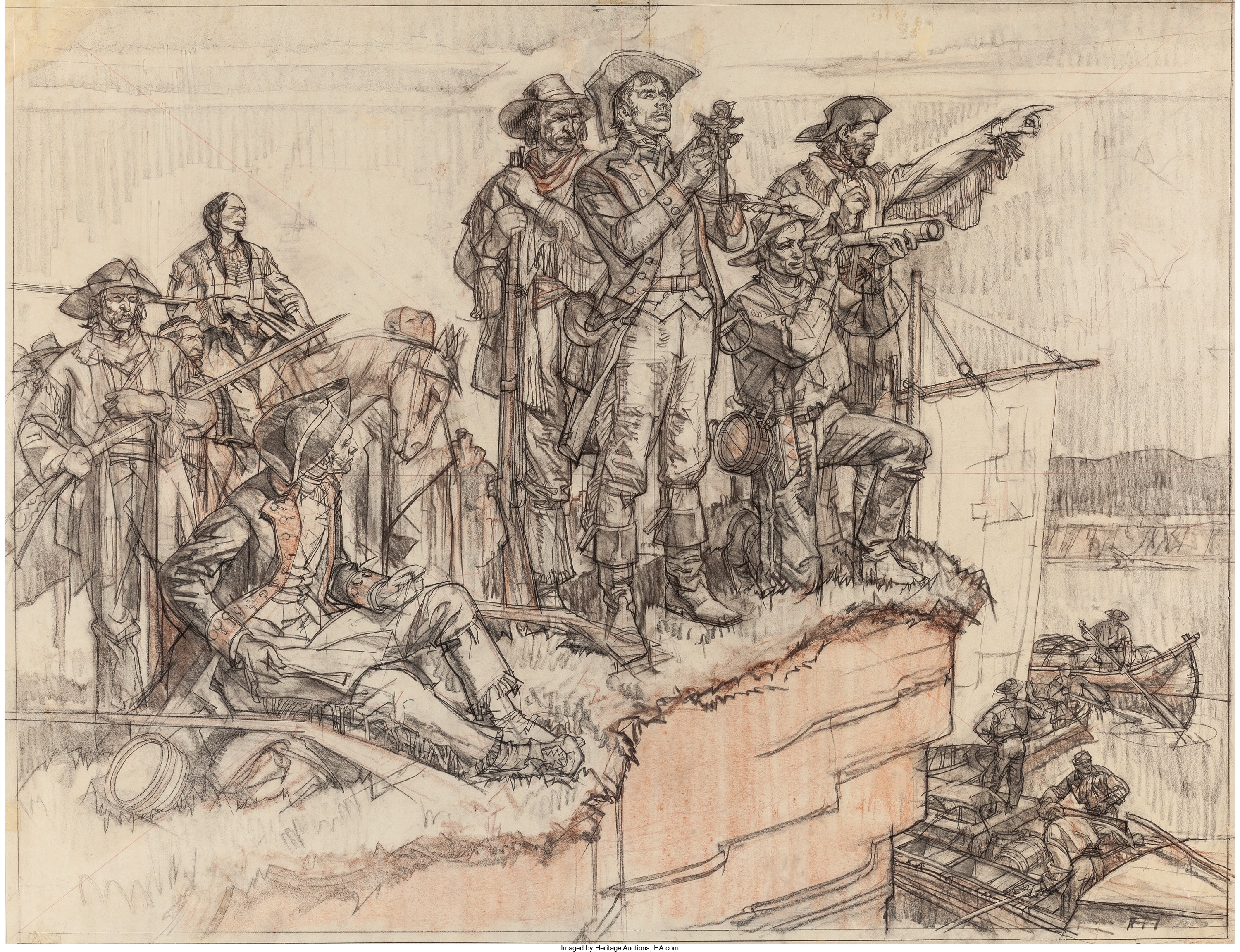

Now it was time to conclude the war with Mexico and all the lingering questions about Spain’s 300 years in North America. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was a convenient mechanism since the Mexican Army was defeated and the capital was occupied. For $15 million, Mexico ceded 55 percent of its total territory, including present-day Arizona, California, New Mexico, Texas, Colorado, Nevada and Utah. The Louisiana Purchase had doubled the size of the United States and this treaty doubled it again … along with providing access to the Pacific Ocean.

President Polk served his four-year term and, as promised, declined to run again. On Nov. 7, 1848 – in the first instance of all states casting presidential ballots on the same day – General Zachary Taylor was elected president. James Polk returned to his home in Nashville, Tenn., and died on June 15, 1849, a mere 103 days after the inauguration … the shortest retirement in history. His mother Jane Knox would die in 1852, marking the first time a president was outlived by his mother.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].