By Jim O’Neal

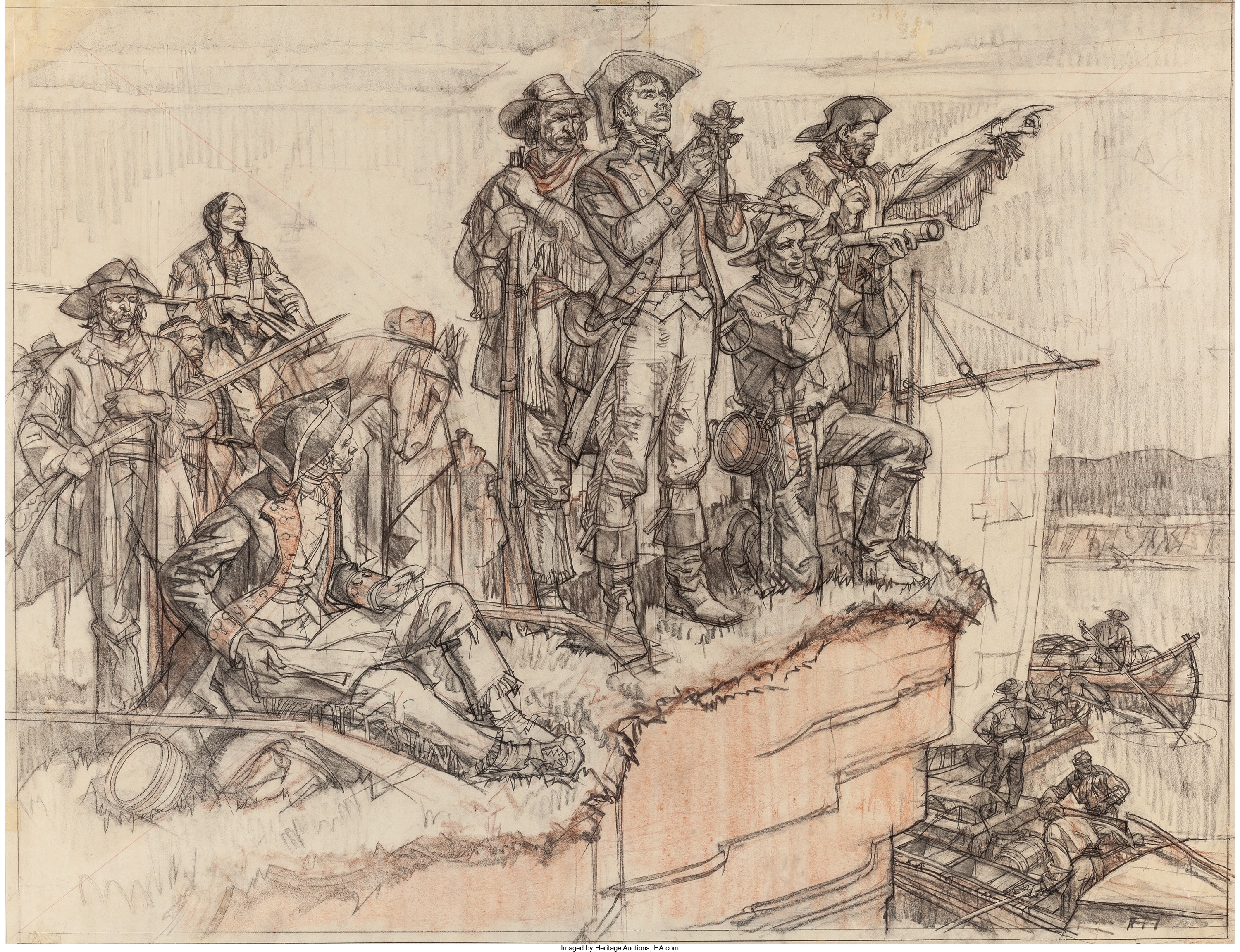

In the 1700s, British fur traders in northern regions between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains came into conflict with Russian traders arriving from the north and the Spanish from the south. Then, Americans began appearing in the early 1800s after the Louisiana Purchase (1803) and the Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804-06).

By this time, England had negotiated a boundary agreement with Spain, but not with the Russians. The British and Americans collaborated to gain leverage over the Russians by agreeing to joint sovereignty over a large area called Oregon Country. The agreement encompassed what is today Oregon, Washington, Idaho, British Columbia and parts of Wyoming, Montana and Alberta that were west of the Continental Divide.

By the 1840s, England and the United States were ready to formally separate their joint interests in Oregon Country, but couldn’t agree on a dividing line. The U.S. demanded it should be 54 parallel-40 degrees, however, this would have deprived GB of Vancouver, their major Pacific port. The dispute escalated into “54-40 or fight” – which became a major theme during the 1844 U.S. presidential election.

After James Knox Polk became president, he rather wisely avoided a war with England by conceding to their demand of 49 degrees. He had his eye on Mexico and decided the United States could only engage in one major skirmish at a time. After the annexation of Texas, war with Mexico seemed inevitable and it arrived right on time, eventually delivering the highly coveted areas of California, New Mexico and Arizona. The concession to England seemed prudent since westward migration had started earlier in 1836. The first migrant wagon train left Independence, Mo., along the Oregon Trail, a 2,170-mile east-west trip that connected the Missouri River to the lush valleys in Oregon.

Then on May 22, 1843, a massive wagon train with 1,000 settlers and more than 1,000 head of cattle set out for Oregon. They followed the Santa Fe Trail for 40 miles and then turned west to the Platte River to Fort Laramie, Wyo., and eventually over the Blue Mountains into Oregon territory. The Great Migration arrived in October, covering 2,000 miles in five months. The next year, four more wagon trains made the journey and in 1845, the number of emigrants exceeded 3,000. “Oregon Fever” seemed to have gripped the nation.

Then in 1848, gold was discovered in California and the flow of people headed there instead of Oregon. The population of California zoomed from 20,000 to 225,000 in four short years. The phrase that summed up America’s assertive development was coined by columnist and editor John O’Sullivan when he wrote, it was “our manifest destiny to overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our yearly multiplying millions.”

Thomas Jefferson thought it would take 1,000 years to fill up the vast emptiness of the west, but of course, he didn’t know about the California gold, the Oregon Trail, and the basic restlessness of future emigrants and the transcontinental railroad. The $15 million he spent on doubling the size of the United States turned out to be one of best real estate deals in history.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].