By Jim O’Neal

On March 3, 1913, the day before the presidential inauguration, the Thomas Woodrow Wilson family arrived in Washington, D.C. There was very scant attention paid to the arrival of the new president-elect since it coincided with an unusually high-profile demonstration.

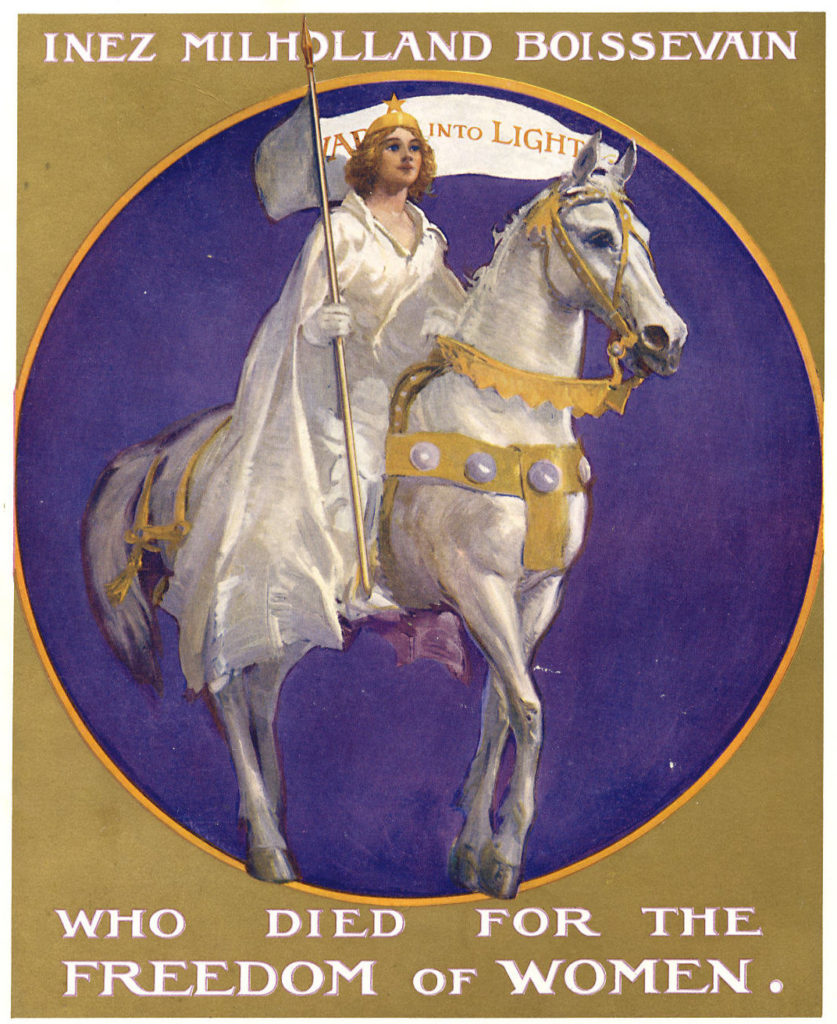

About 8,000 women, led by Vassar-educated lawyer Inez Milholland Boissevain (astride a beautiful white horse), were marching in the capital’s streets to further the cause of women’s suffrage. There were marching bands, floats and pageantry galore along the route. The demonstration was intended to emphasize frustrations with the slow progress in Congress, despite the many years of effort to gain national rights.

Prior to 1912, only 1.3 million women in six states had equal voting rights with men and a mere three states had been added for a grand total of nine. However, the movement seemed to be gaining broader support, although eight more years would be needed before the 19th Amendment was approved.

On this particular day, the crowds were boisterous and opponents took delight in spitting on their banners and throwing lighted cigarettes and cigars at and on marchers. At times, the crowds got out of control and more than 100 people were trampled or bruised to the point they required hospital care.

The three Wilson daughters, Margaret, Jessie and Eleanor (nicknamed Nellie), were all ardent supporters of women’s suffrage and were constantly badgering their father to make it a priority even before he was elected. Jessie had even taken a bold stance while in college and ended up resigning from her sorority when her efforts were scorned.

Jessie Woodrow Wilson was born on Aug. 28, 1887, and educated far beyond most women of the day, similar to outgoing First Lady Helen Taft. She had studied at Goucher College and Princeton, where she was Phi Betta Kappa after her high academic accomplishments. After college, she worked at the Lighthouse Settlement House for women millworkers, where she observed firsthand the downtrodden women, and it transformed her into a passionate supporter of women’s suffrage and equal rights.

In 1915, Margaret acted as honorary hostess for the convention of the National American Women Suffrage Association (later known as the League of Women Voters) and Eleanor would speak at the convention along with members of her father’s cabinet. 1915 was also the first year a U.S. president would attend the World Series. The Philadelphia Phillies won the first game, but it would take 65 years before the next one (1980). The Red Sox easily won the series 4-1. Their pitching staff was so good that a young pitching star named George “Babe” Ruth was limited to a single appearance as a pinch-hitter (he grounded out).

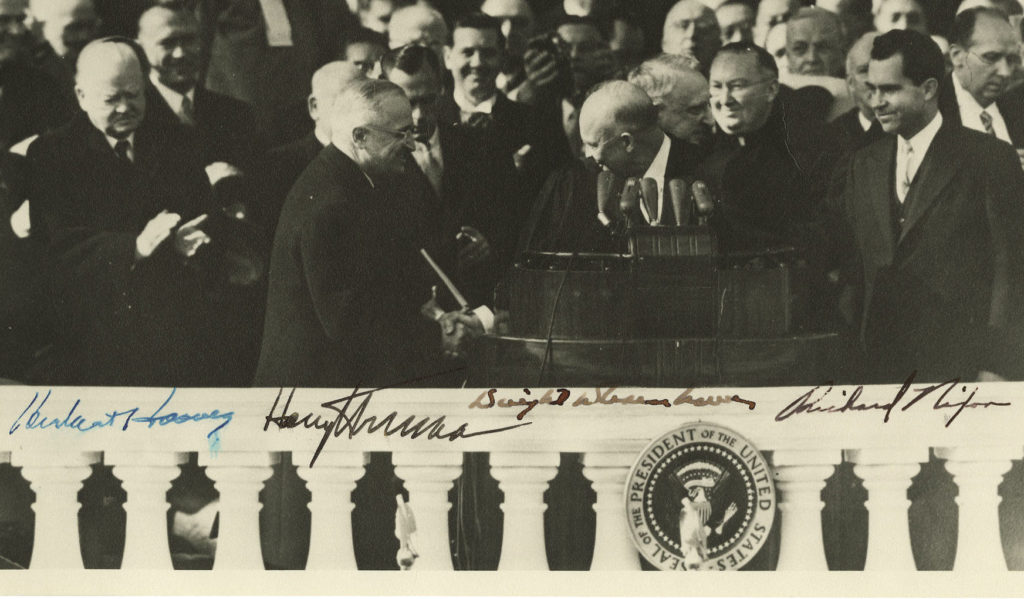

Jessie Wilson continued her political career and even introduced Al Smith as the first Catholic presidential nominee in 1928 (he lost to Herbert Hoover), and was obviously poised for big things when Franklin D. Roosevelt won the first of his four elections and dominated the Democratic Party.

Alas, on Jan. 15, 1933, Jessie Woodrow Wilson Sayre died at age 45 following complications from abdominal surgery. I suspect she would have been heavily involved in politics had she lived a longer life.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is President and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as Chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is President and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as Chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].