By Jim O’Neal

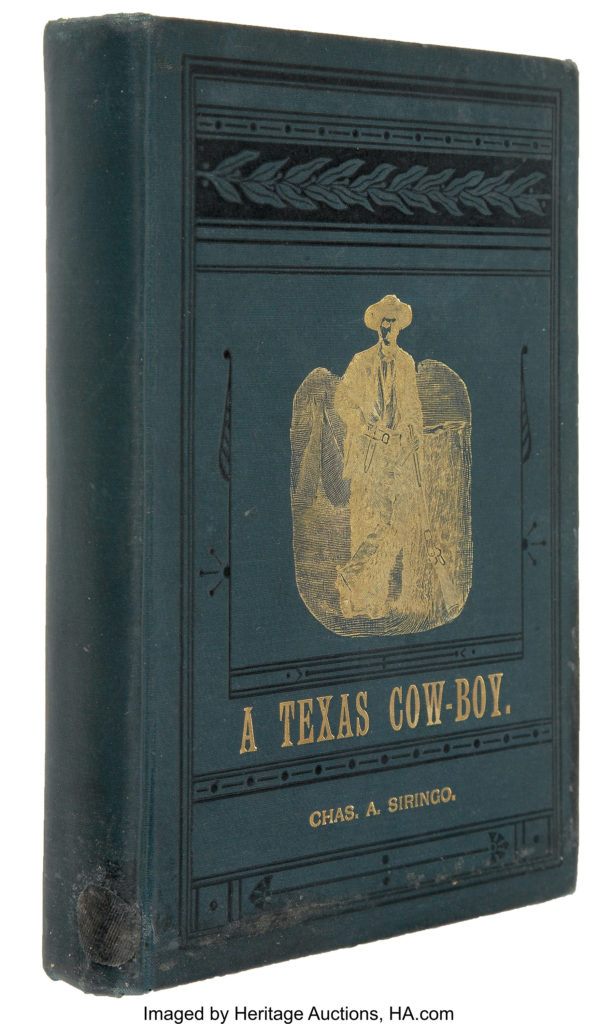

In 1885, Charles Siringo published his first book. It was an autobiography with the long and awkward title A Texas Cow-Boy; Or Fifteen Years on the Hurricane Deck of a Spanish Pony. It may have been a slight exaggeration to claim it sold a million copies (accounts vary). However, it was definitely plausible, since it was the first authentic book written by a genuine working cowboy.

Siringo had a reputation for being a reckless but courageous cowboy who was an expert shot with his reliable six-shooter. This was a fascinating combination and, when added to his real-life experiences, was exactly what ranch hands and dreamy-eyed city dwellers were eager to read about.

It’s doubtful that anyone was remotely aware of just how insatiable the public appetite was for stories about the exciting American West or the paucity of books or magazines available. This was a mysterious place filled with cowboys, ranchers, outlaws rustlers, Indians and lawmen. Stories about the “Wild West” were to become bestsellers beyond wildest imaginations.

Charles Siringo was born in Texas in 1855 and, after a few rudimentary lessons, became a cowpuncher. While still a teenager, he had his own registered brand and dreams of one day having a big ranch. This was still possible by simply rounding up a bunch of “mavericks” – unbranded cows wandering the open range – claiming ownership and slapping your own brand on them. He was never able to build much of a herd and ended up as a shopkeeper in Kansas for a few years.

However, before he was 30 years old, he had plenty of stories and a zeal for making money. The book he wrote was an immediate success and played a pivotal role in creating the enduring American fascination with the Western cowboy. He had spent 20 years working as a Pinkerton detective chasing rustlers and train robbers, sometimes even going undercover and infiltrating gangs of outlaws. Some of his more notable exploits included chasing Butch Cassidy and his “Wild Bunch” all over the Southwest until they escaped to South America (much to the relief of the railroad owners). Earlier, he and Sheriff Pat Garrett put an end to the career of Billy the Kid in a famous gunfight.

He finally left Pinkerton in 1907 but had enough real-life experience to write five more novels. He died in Altadena, Calif., in 1928 at age 73, probably unaware of just how popular stories of the West would become in books, movies and television.

By fate or coincidence, 10 years later, the most prolific chronicler of the American West would also be buried in Altadena, but this storyteller made a fortune and was the first author to become a millionaire. It was none other than the incomparable Zane Grey (1872-1939). Nobody comes close to spinning tales of this genre for so long and in every media available.

Zane Grey was from Zanesville, Ohio, and would become the best selling Western author of all time. From 1917 to 1926, he was one of the top 10 bestsellers nine times and is credited with sales of over a staggering 40 million books. Then, when the paperback format was introduced, most of his books were reissued into mass distribution.

Hollywood eagerly turned most of his stories into over 50 movies. His bestseller was 1912’s Riders of the Purple Sage; Grey sold the movie rights to motion-picture executive William Fox for $2,500. Fox went on to sell his company and it eventually grew into an entertainment giant. Last week, Disney bought 21st Century Fox for $71 billion.

Zane Grey books and movies easily made the transition to television. Dick Powell’s Zane Grey Theatre ran on CBS from 1956 to 1961 with 149 episodes. Uniquely, five episodes were so popular they ended up being spun off into their own shows: Trackdown (Robert Culp), The Rifleman (Chuck Connors), The Westerner (Brian Keith), Black Saddle (Peter Breck), and Johnny Ringo (Don Durant). And, of course, there was Grey’s novel The Lone Star Ranger, which spawned four movie adaptions.

I grew up going to the movies every Saturday and I tried to see every Western at least twice. This addiction carried over into television and I loved them all, memorizing all the actors and their role names. Somewhere in this repertoire, I suspect you will recall a favorite.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].