By Jim O’Neal

French President (General) Charles de Gaulle was known for reminding his aides that “the world’s graveyards were filled with indispensable men.” Skeptics were offered a simple test: Stick a finger into a glass of water and describe the hole it leaves when it is removed. Somewhat quirky, but remember this was a France where de Gaulle complained “How can you govern a country which has 246 varieties of cheese?” Sacré bleu!

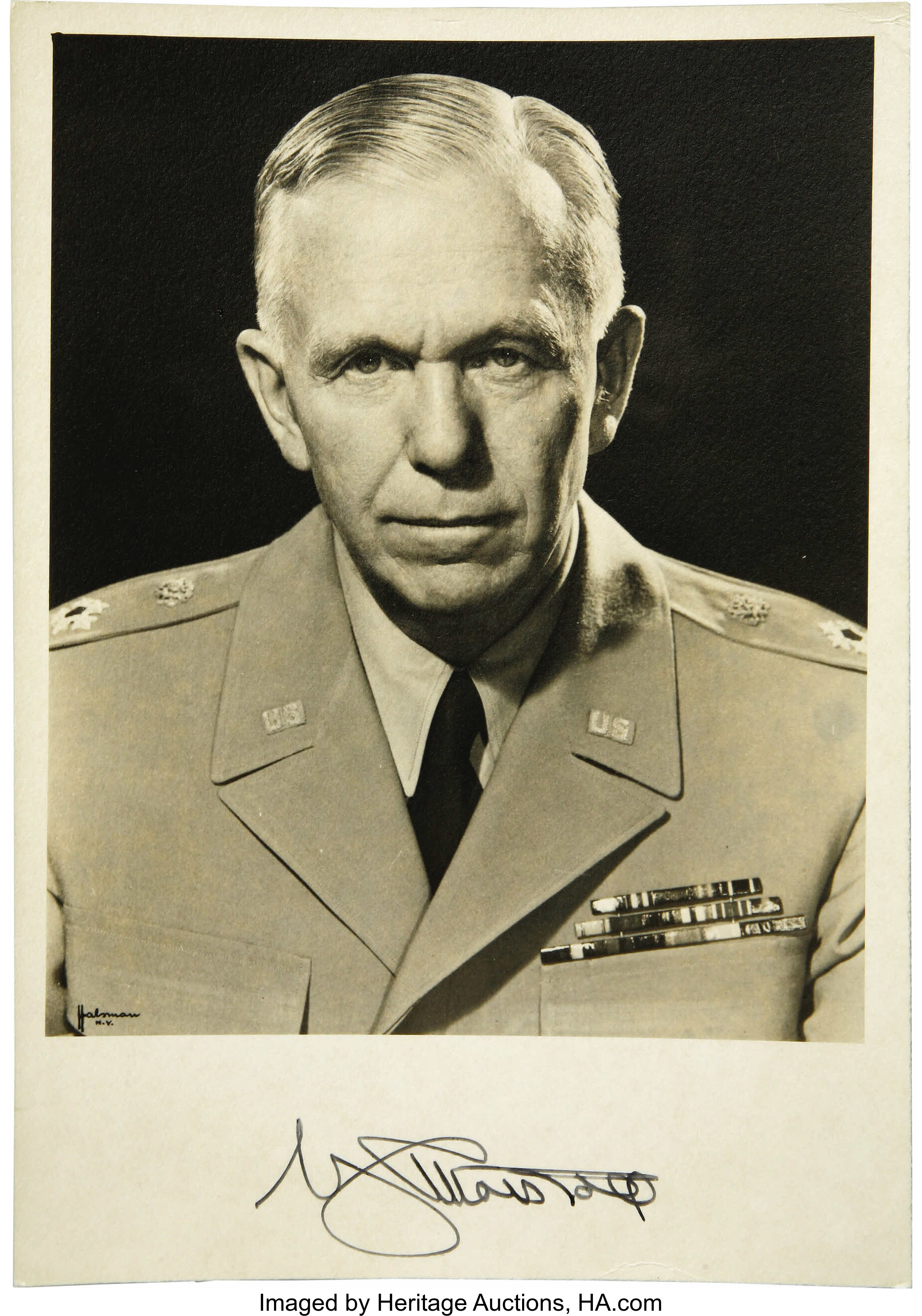

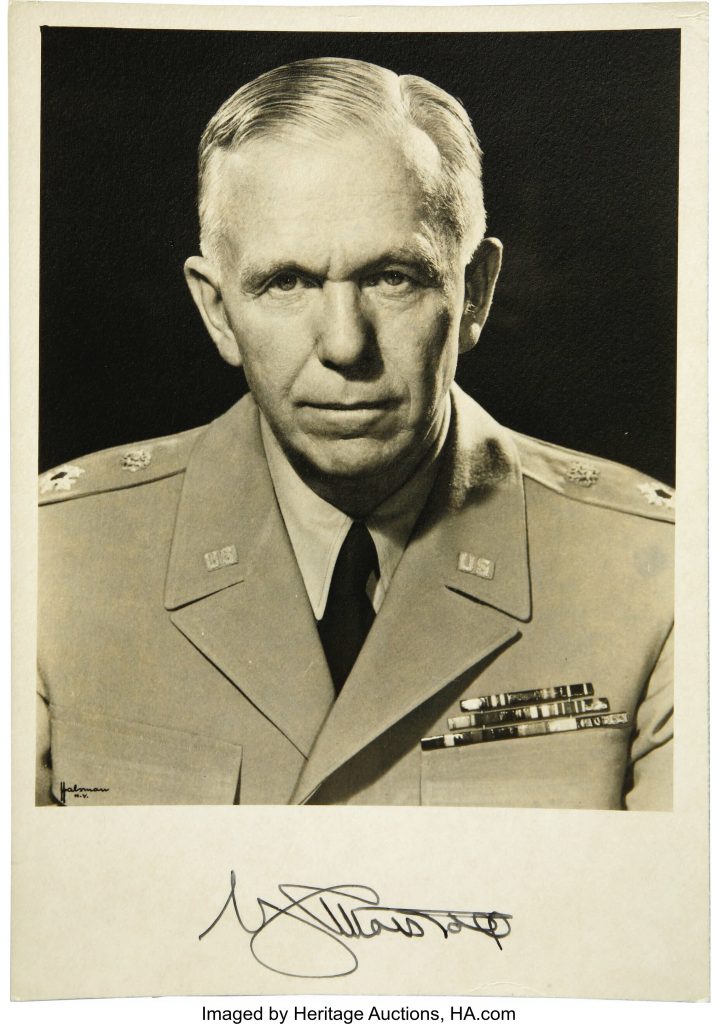

I suspect Amazon would yawn at the degree of complexity implied, but they have become almost indispensable in our home, just as George C. Marshall (1880-1959) was indispensable during his remarkable 50 years of service to the United States. When he died, he left behind a cadre of admirers like Harvard President James Conant, who declared that only George Washington was Marshall’s equal as soldier/statesman (which overlooks Marshall’s superb diplomatic skills). Others like Winston Churchill went even further, crediting Marshall with high praise as the “Organizer of Victory.” Recall that when Churchill was asked what history would say about him, he deftly replied, “History will be very kind to me. I plan to write it!” And he certainly did with his six-volume “The History of the Second World War.”

In order to squeeze in a small insight into George Marshall’s extensive career, it is useful to start at the beginning of the 20th century. The Russian Empire, ruled by Czar Nicholas II, was probably the largest territorial power in the world, with control over Eastern Europe and Central Asia. But they lacked a warm water port and had ambitions that included Korea and China. Japan was dominant in Asia and the two clashed in 1904-05, primarily in northeastern China and the waters surrounding the Korean peninsula.

The Russo-Japanese War sowed the seeds for World War I and although Japan, surprisingly, eventually prevailed, President Teddy Roosevelt won the Nobel Prize for brokering the Treaty of Portsmouth (Sept. 5, 1905), which formally ended the war. Some historians now call this episode World War Zero, since it was so closely linked to what followed a mere 10 years later.

Enter George Catlett Marshall Jr. on the last day of August 1899, when he decided to become an officer in the U.S. Army. However, his ascent to prominence and power began on Jan. 27, 1914 when 5,000 U.S. Army soldiers landed on Luzon and prepared to attack Manila, some 60 miles away. It was a maneuver to test the readiness against an attack on the Philippines by Japan. After defeating the Russians, the Japanese had completed the entire annexation of Korea and the American–controlled Philippines was logically next up.

The 34–year–old Lieutenant Marshall choreographed the myriad details of the mock invasion and eight days later it was being hailed as a brilliant success. The word began to spread widely that Marshall was not only a military genius, but one of the most talented strategic thinkers in the entire Army. General Henry “Hap” Arnold would write that he had “met a man who was going to be the Chief of Staff someday soon.” Arnold would have the distinction of holding the ranks of General of the Army and General of the Air Force. He was the only U.S. Air Force General to hold the five-star rank and the only officer to hold five-star rank in two different U.S. military services. He was a keen judge of talent and George Marshall would benefit during WW2.

Marshall assumed the position as Army Chief of Staff on the same day German Panzers attacked Poland and proceeded to transform our nation’s modest military forces into the most powerful war machine the world has ever seen. In addition to guiding global strategy, he demonstrated a unique ability to win the trust of both political parties, unionists, isolationists, pro–war factions and, importantly, the U.S. Congress. The result was legislation that enabled the country to wage war on both sides of the globe, with the full support of virtually every American.

Marshall was responsible for turning raw draftees into trained fighters while running military logistics in Europe, the Pacific, China and the Mediterranean. His genius for balancing economic, political and pragmatism with the gift of eloquence shaped the willpower of military staff and world leaders FDR, Winston Churchill, Joseph Stalin and even prima donna generals like Douglas MacArthur, who tended to be highly independent.

Instinctively, he recognized the strategic advantage of attacking France to regain control of Europe and was widely viewed as the logical commander to lead the D-Day invasion. Instead, this quiet man from Pennsylvania, who had become the nation’s first five-star general, was considered too valuable to the overall war effort and General Eisenhower was selected. President Roosevelt explained to him, “I didn’t feel that I could sleep at ease if you were out of Washington, D.C.” Eisenhower could handle the massive amphibious assault, but only Marshall could be trusted to manage both wars.

Finally, after all the guns and bombs fell silent, the 64–year-old indispensable man was ready to retire. However, fate intervened and President Truman asked him to help reconcile post-war China, but the Communists prevailed over Chiang Kai-shek, who fled to Taiwan. Then Truman fired his Secretary of State and called on Marshall once again. Despite being retired, five-star generals were still considered to be subject to service. Next, he became the Secretary of Defense. Later, when Truman was asked about who had contributed the most over the past 30 years, Truman picked Marshall: “I don’t think in this age in which I’ve lived that there has been a greater administrator; a man with a knowledge of military affairs equal to George Marshall.”

Amen.

He received the Nobel Peace Prize for his post-war work in 1953, the only career officer in the U.S. Army to ever receive this honor. The Marshall Plan merely saved Europe by restoring a broad area that had been devastated by the war and gave them an opportunity to rebuild and thrive during the 20th century. R.I.P.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].