By Jim O’Neal

On Easter Sunday 1913, a great tornado ripped through Omaha, Neb. As people scrambled for cover, a naked man was blown through a dining-room window. He grabbed the tablecloth to use as a toga and politely asked the startled family for a pair of trousers. The local newspaper dubbed him the “human meteorite” and went on to report how the twister sucked two babies out the window of the town orphanage. Another man reported the body of a 4-year-old girl dropped out of the sky into his arms, while cows were impaled on fence posts and chickens were plucked clean. That night, another dozen clouds raced across Iowa, Illinois, Missouri, Michigan and Indiana.

After the storms’ initial volley, heavy rains began to fall, swelling the Ohio River until its levees could no longer stem the angry waters and they were breached. The submerged cities included Fort Wayne, Columbus, Cincinnati and Indianapolis. However, Dayton, Ohio, was hardest hit as the Miami River rushed downtown, washing away homes and stranding residents on roofs, buildings and even telephone poles.

Dayton-based businessman John Patterson (1844-1922) immediately seized command and converted a factory assembly line to turn out rowboats for use in rescuing trapped inhabitants. A large plant cafeteria started baking bread and other foodstuffs. Most of Dayton’s provisions were either underwater or ruined by floodwaters. Many of the town’s residents owed their lives to Patterson’s quick actions. Still, over 300 people perished and damages topped $2 billion.

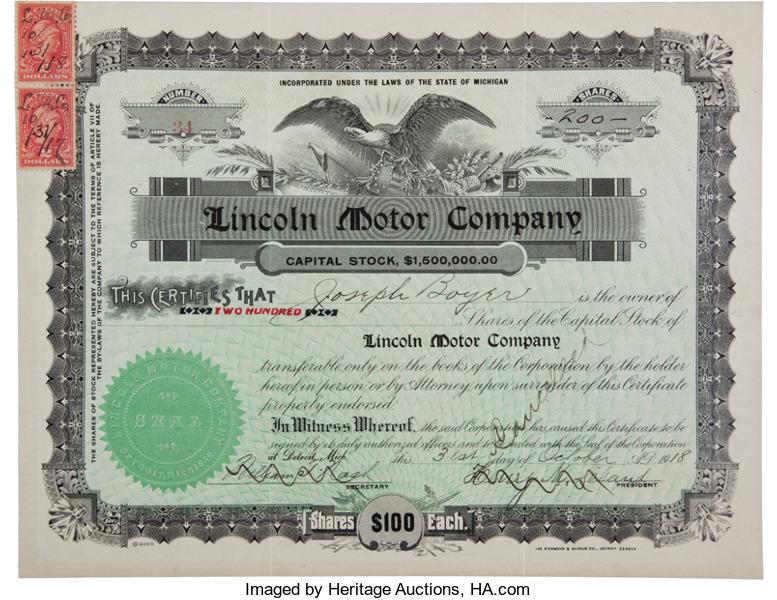

Patterson had launched his business career in December 1884 when he purchased the rights for “Ritty’s Incorruptible Cashier” for $6,500. James Ritty (1836-1918) was an Ohio bar owner who discovered what all bar/restaurant owners eventually learn: Employees inevitably start pilfering cash, booze or food. Many a chef has walked out with a ham or turkey under their coat on the way home. Or perhaps served friends and relatives drinks without keeping tabs.

Ritty’s invention was a machine positioned atop an adding machine that kept track of orders or controlled the cash. Patterson improved the design by adding the now familiar pop-up number, a cash drawer and a bell that rang when employees used it. He quickly recognized the potential profit in selling the machine to various retail merchants. All were potential customers. Thus, the National Cash Register Company was formed and Patterson went to work developing a skilled sales organization. Trainees were enrolled in a “Hall of Industrial Education” and after graduating, received their own exclusive territory to sell the new invention.

It was an immediate success and the company gained a reputation for generous commissions. A new factory was built with glass walls so the sun could shine through. This was the era when most factories were called “sweatshops” for good reason. In addition, Patterson included free medical clinics, a swimming pool and an employee cafeteria serving healthy food. The grounds were sculptured landscapes designed by architect John Charles Olmsted.

Patterson was a demanding boss and the list of future prominent businessmen he fired was a long one. One was Thomas Watson Sr. (1874-1956), who owned a butcher shop with a shiny NCR cash register. After the business failed, Watson went to work at NCR until Patterson fired him. Watson would go on the build International Business Machines (IBM) into a world-class institution. Another was Charles Kettering (1876-1958), a near genius engineer who went to work for General Motors after he was fired several times. He would head up GM’s engineering research department for 30 years. In addition to inventing the automobile electric self-starter, he recorded 186 patents and became a towering member of the Inventor Hall of Fame.

Patterson was a ruthless competitor and built a “gloom room” filled with cash registers from all the competing companies he ruined. In 1912, the company was found guilty of violating the Sherman Antitrust Act after acquiring over 80 direct competitors and ending up with a 95 percent market share. Patterson and 26 of his executives were headed to jail for a year after President Wilson refused to pardon them.

But fate intervened and an appeal overturned the conviction, partially because of Patterson’s good deeds during the Great Flood of 1913. Dayton welcomed them with a giant parade.

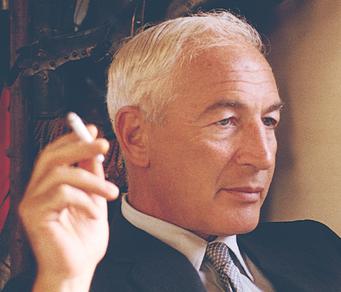

Pardons can be tricky for presidents, but all have used the power. Franklin Roosevelt holds the record with more than 3,600 acts of clemency! Since they were spread over four terms, there was not much political criticism. President Clinton was not so fortunate. On Jan. 20, 2001, his last day in office, he granted 140 pardons. One was to Marc Rich, an international commodities trader indicted by U.S. Attorney Rudy Giuliani in 1983 on 65 criminal counts involving income tax evasion, wire fraud and racketeering. Rich fled the United States.

When it was revealed he was still a fugitive and the pardon had been handled by Jack Quinn, it caused an uproar from both prominent Democrats and Republicans (Quinn had been Clinton’s White House Counsel). Then things escalated when it was discovered his ex-wife made donations to the DNC, the Clinton library, and Hillary’s Senate race. Attorney General John Ashcroft asked federal prosecutor Mary Jo White to investigate, but James Comey took the lead when White left the government. The probe was closed down after federal investigators ultimately found no evidence of criminal activity.

Hmmn. Giuliani, Clinton, Comey. Small town.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].