By Jim O’Neal

One of the primary problems facing the federal government when the Civil War began was ensuring that its employees and military were loyal. Over 300 U.S. officers resigned to join the Confederacy, as did numerous clerks and officials. Fearful of disloyalty among those who remained, President Lincoln on April 30, 1861, ordered all military personnel to retake an oath of allegiance.

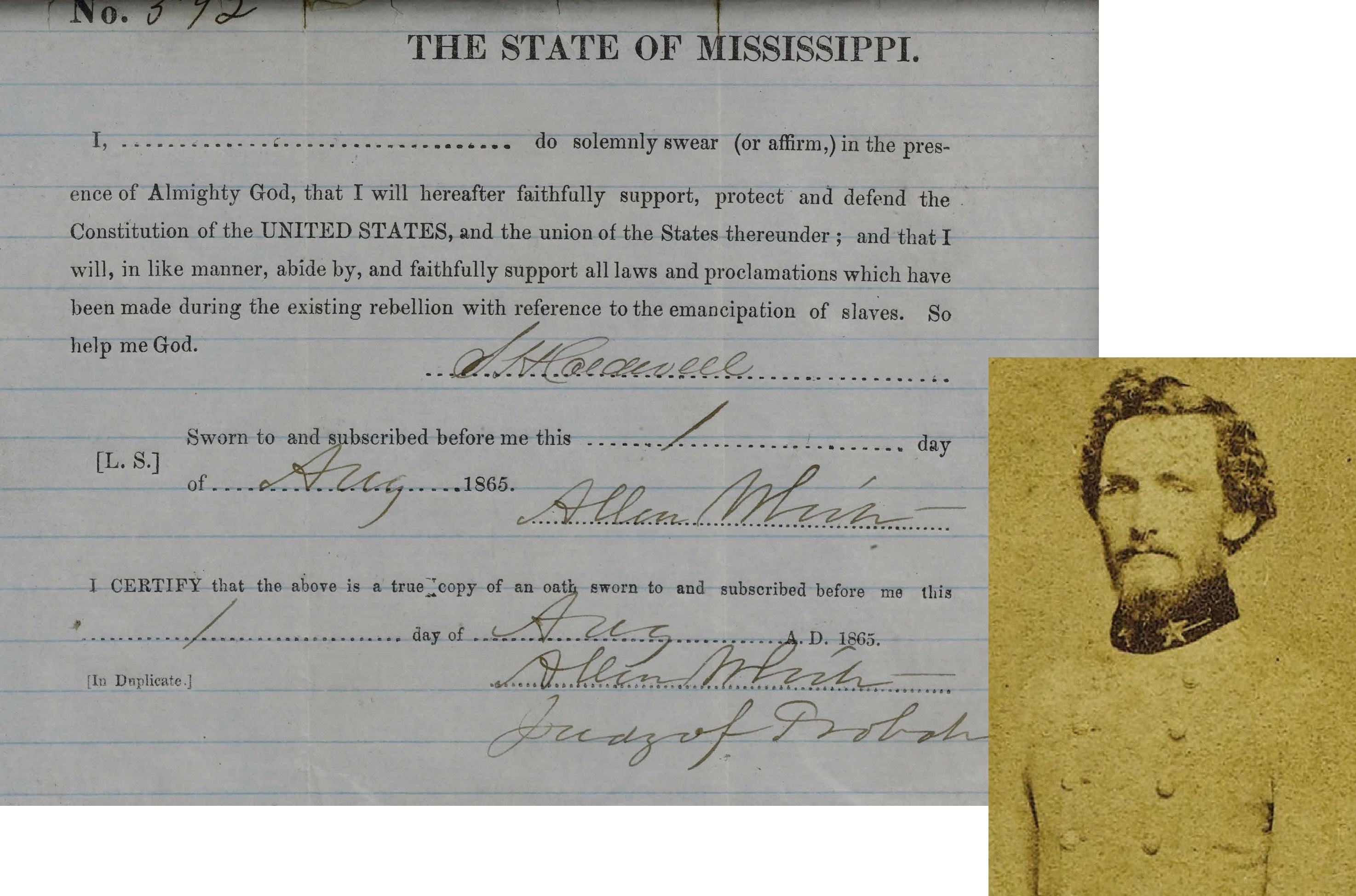

Even though these regulations were rigidly enforced, fears of disloyalty remained and numerous ad hoc oaths of allegiance were used as a means of testing and ensuring loyalty. By the summer of 1862, most of the oaths – civil and military – were combined under one oath, the Ironclad Test Oath of Loyalty.

The Ironclad Oath was named because it required an oath-taker to swear, “I have never voluntarily borne arms against the United States.” In addition, the person had to forsake any allegiance to state authority and swear “to support and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies foreign and domestic … [and] bear true faith and allegiance to the same.”

An oath of allegiance rapidly became a test of loyalty for common citizens. Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler as military governor of New Orleans required that after Oct. 12, 1861, anyone who wanted to do business in the city or with the U.S. government had to take an oath of allegiance to the United States. As stated by Butler, “It enables the recipient to say, I am an American citizen, the highest title known.”

Butler’s practice became commonplace as the war progressed, and the Ironclad Oath, or a variant, was required of thousands of federals and Southerners. People who wanted to do business with the government, Confederate prisoners of war who wanted parole, Southerners who wanted to be reimbursed for goods taken by foraging federal troops, and Union sympathizers in the South who wanted to govern themselves – all took the oath. Some took it numerous times; the record may have been set by politician Robert J. Breckinridge, who took the oath nine times between June and December 1865.

After the war, the oath presented an immediate problem for both the South and North. Since its provisions remained in effect, no former Confederate soldier or Southern citizen who had assisted in the South’s war effort could hold federal, state or local office, or serve in the military. To evade the “ironclad” portion of the oath concerning bearing arms against the United States, former Confederates had to petition the president of the United States for a pardon.

In 1884, Congress removed all the iron from the Ironclad Oath when it passed into law a new Oath of Allegiance. The 1884 oath removed all the restrictive portions of the older oaths and left it in its current form – an oath to support and defend the Constitution.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].