By Jim O’Neal

When I started studying the history of war in early 1962, I was surprised that so many wise military men all warned about the danger of a land war in Asia. Words like “bogged down,” “embroiled” and “mired” were liberally sprinkled around in the hope of shaping foreign policy. I knew President Eisenhower had quickly ended the “police action” in Korea that President Truman had left unfinished. As an experienced military strategist, Eisenhower knew that fighting on the Korean Peninsula could easily expand into a direct confrontation with China. He had been determined to avoid restarting the global conflict he had helped end.

The 1950s were a good time for America as we helped rebuild the world.

Then the seeds of war in Vietnam started slowly showing up on the evening news. The implications were blurred by events in San Francisco. Hippies, flower children, sex, drugs and rock ’n’ roll were far more entertaining. President Johnson started complaining about “JFK’s war” while he and Secretary of Defense Bob McNamara were quietly acceding to military requests for more troops and guns.

Eventually, draft protests grew more violent, followed by riots in major cities and MLK and Bobby Kennedy being assassinated. By 1968, the United States had 550,000 troops in Vietnam, having steadily grown from a few hundred “military advisers.” It would take another seven years and a different president to extricate the nation from an incremental war that had caused such domestic turmoil. The Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C., lists 58,318 names (including eight women) as of May 2017 who were “declared dead.”

The wise military officers had been right.

One hundred years earlier, a similar series of events had culminated in a civil war. In the three months following President Lincoln’s election, seven states seceded from the Union. The new president was paranoid that the Confederates would attack Washington after they forced the garrison at Fort Sumter to surrender. He urged his military advisers to preemptively attack rebel forces in Virginia, but the Union army lacked training and was too slow.

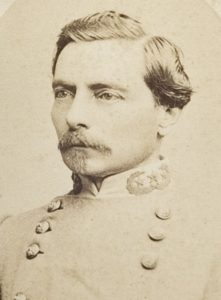

Finally, on July 16, 1861, Union General Irvin McDowell led 33,000 slightly trained soldiers toward Manassas, Va. (later better known as Bull Run). Before they arrived, spies tipped off P.G.T. Beauregard, who quickly called for 10,000 reinforcements to bolster his 22,000 troops. Rumors of the pending battle spread quickly and there was a large contingent of politicians and civilians perched on a hillside with blankets and picnic baskets, eager to see a good fight. Among them was a young senator from Ohio, John Sherman, whose brother William Tecumseh would play a key role with General Ulysses S. Grant in ending the war.

However, 10 hours of combat on July 21, 1861, changed the way a nation viewed war. Both Federals and Confederates had come to these fields supremely confident of swift, relatively bloodless victories. Even Abraham Lincoln had attended church that day after being assured of an easy Union victory. Senator Sherman was one of the first to learn otherwise. “Our army is defeated and my brother is dead,” Secretary of War Simon Cameron informed him.

They left behind more than 800 dead and 2,700 wounded. They also left behind any illusions that the war would be won or lost on a single, lazy Sunday afternoon. Confederate officer Samuel Melton wrote, “I have no idea that they intend to give up the fight. On the contrary, five men will rise up where one has been killed, and in my opinion, the war will have to be continued to the bloody end.”

Another wise man who understood war.

Now flash forward to October 1998 when official U.S. foreign policy was changed by a benign-sounding Congressional action to remove the Iraqi government: the Iraq Liberation Act. Then, four years later in October 2002, the U.S. Congress passed the “Iraq Resolution,” which authorized the president to “use any means necessary” against Iraq. At 5:34 a.m. Baghdad time on March 20, 2003, the military invasion of Iraq began. Fifteen years later, we are still in Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya, Syria and Niger. Some now call this the “long war” and there is no end in sight.

My friend Colin Powell says he did not invent the “Pottery Barn Rule” (if you break it, you own it). But he does believe that any war should have a clear objective, an overwhelming force to achieve it and a clear exit strategy.

He is a wise man.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].