By Jim O’Neal

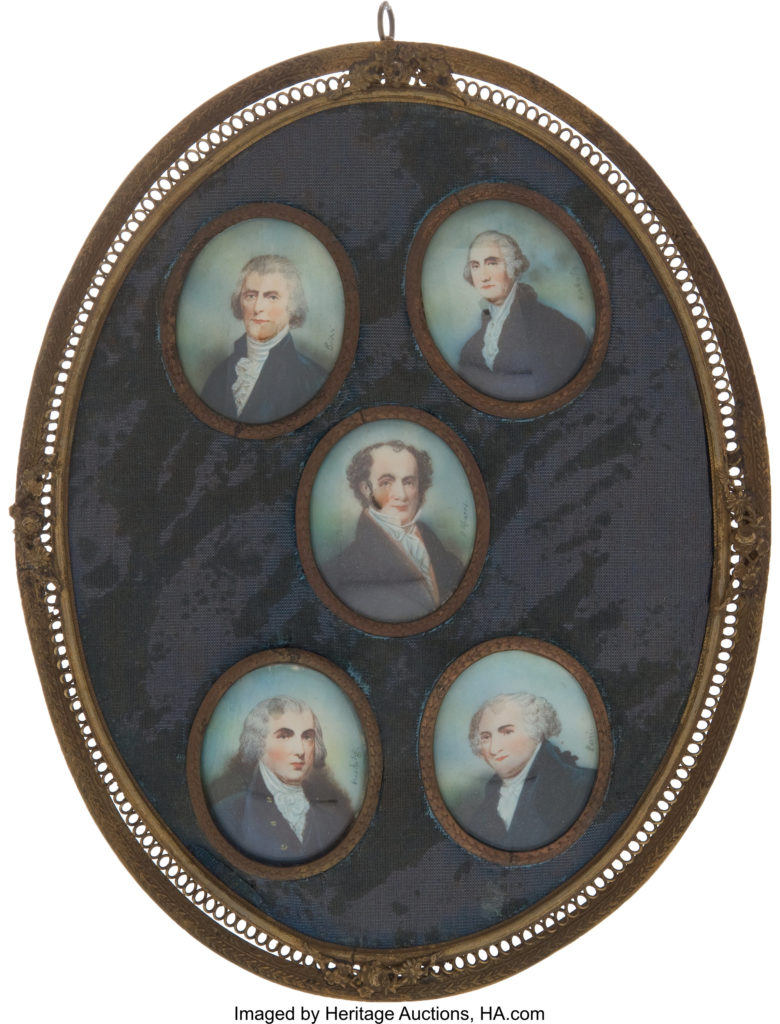

Andrew Jackson had been denied the presidency in the election of 1824, despite winning most of the popular votes and electoral votes. In situations where a political candidate did not secure a majority, the House of Representatives decided which of the top three candidates (by vote totals) would become president. The top three in 1824 were Jackson, John Quincy Adams and William Crawford. Henry Clay had finished fourth and was dropped from consideration.

The House then voted and picked Adams for president and he subsequently appointed Clay to be Secretary of State. Critics claimed that Clay had persuaded the House to vote for Adams in a secret quid pro quo for the Cabinet position. The dispute became notorious and was dubbed “the Corrupt Bargain” by Jackson supporters.

However, Jackson bounced back four years later and soundly defeated JQA for the presidency. This was the second time an incumbent president had been defeated. Thomas Jefferson had defeated President John Adams in the election of 1800. Both Adamses, father and son, were bitter about their defeats, and the “Era of Good Feelings” that existed for eight years (1817-1825) under President James Monroe came to an abrupt end. The deterioration into partisan politics was precisely what George Washington had warned about if political parties were allowed to flourish. He was a man wise beyond his years, as we know so well today.

After Jackson served two tumultuous terms (1829-1837), the Hero of New Orleans was tired and ready to go home. He had abandoned the idea of a third term and even seriously considered an early retirement that would allow close friend and adviser Vice President Martin Van Buren to assume the presidency. This would help ensure a peaceful continuation of Jacksonianism and put Van Buren in a strong place for the 1836 election. Van Buren consistently opposed this and finally the idea was dropped. Jackson would patiently wait for the end of his term.

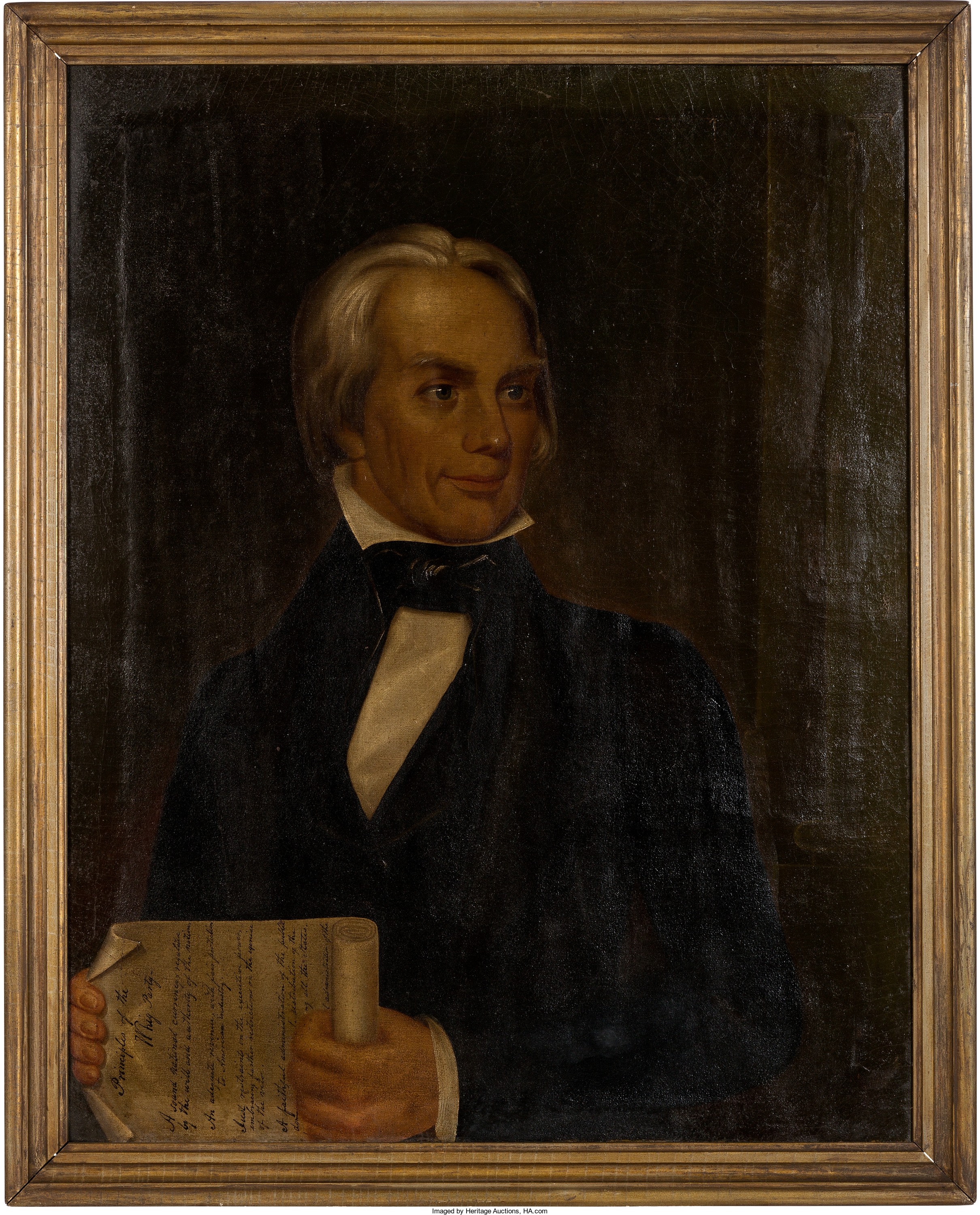

However, earlier in 1835, Jackson had strongly urged party leaders to hold a national convention composed of delegates “fresh from the people” to pick the nominees. He made no secret of his personal preferences: Martin Van Buren for president and Col. Richard Johnson of Kentucky for vice president. This was not a popular choice, especially in the South, where many considered Van Buren a slick New York politician and Johnson worse … much worse. Johnson was anathema to Southerners. His common-law wife was a black woman and they had two children, which Johnson openly acknowledged.

To others, the “Van Buren Convention” was a farce. They complained that several states didn’t send delegates and others sent too many. They singled out Tennessee, which didn’t have delegates, but simply found a merchant from Tennessee who was in Baltimore on business at the time, quickly admitted him to the convention and allowed him to cast all 15 Tennessee votes for Van Buren and Johnson. His name was Edward Rucker and “ruckerize” (assuming a position or function without credentials) entered the jargon as a pejorative with an easy definition. Eventually, Van Buren and Johnson were selected as the Democratic-Republican Party ticket, with the delegates from Virginia hissing as they walked out of the convention.

Van Buren’s opposition in 1836 was composed of various anti-Jackson parties that had formed a new party called the Whigs. The old English Whigs had fought against royal despotism, and the American Whigs were dedicated to fighting “King Andrew the 1st.” They were too dispersed to hold a national meeting, so they simply nominated regional favorite sons: Daniel Webster (New England), Senator Hugh White (South) and General William Henry Harrison (West). Their hope was to divide the electoral vote, deny Van Buren the majority and have the election settled in the House as in 1824.

The strategy failed as Van Buren got almost 51 percent of the vote and was elected president. Richard Johnson had a tougher time. Twenty-three of the Virginia delegates refused to vote for him as “faithless electors” and he was one vote short of the 148 requirements. This time, the VP election was tossed to the Senate and for the only time in history, the Senate elected the vice president of the United States, 34 to 16.

Concurrently, word was received in Washington that Sam Houston had taken the president of Mexico as a prisoner, and Texas was applying for annexation as a state. Jackson was hesitant to accept a new state over the slavery issue. However, on the last day of his term of office, he recognized Texas independence – setting the stage for future annexation. Two days later, after handing over the reins of government to now-President Martin Van Buren, he left Washington by train to return to his beloved Hermitage.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].