By Jim O’Neal

As North Korea continues to relentlessly pursue offensive atomic weapons – perhaps a weaponized missile delivered by a submersible vessel – the world is perplexed over how to respond. U.S. sanctions are ignored, China is permissive, complicit or both, and South Korea and Japan grow more anxious as the United Nations is irrelevant, as usual.

Concurrently, polls indicate that attitudes about the use of atomic bombs against Japan to end World War II are less favorable. But this was not always the case.

At first, most people had approved the use of the bomb on Hiroshima, followed by a second bomb a few days later on Nagasaki. They agreed the bombs hastened the end of the war and saved more American lives than they had taken from the Japanese. Most people shared the view of President Truman and the majority of the defense establishment: The bomb was just an extension of modern weapons technology.

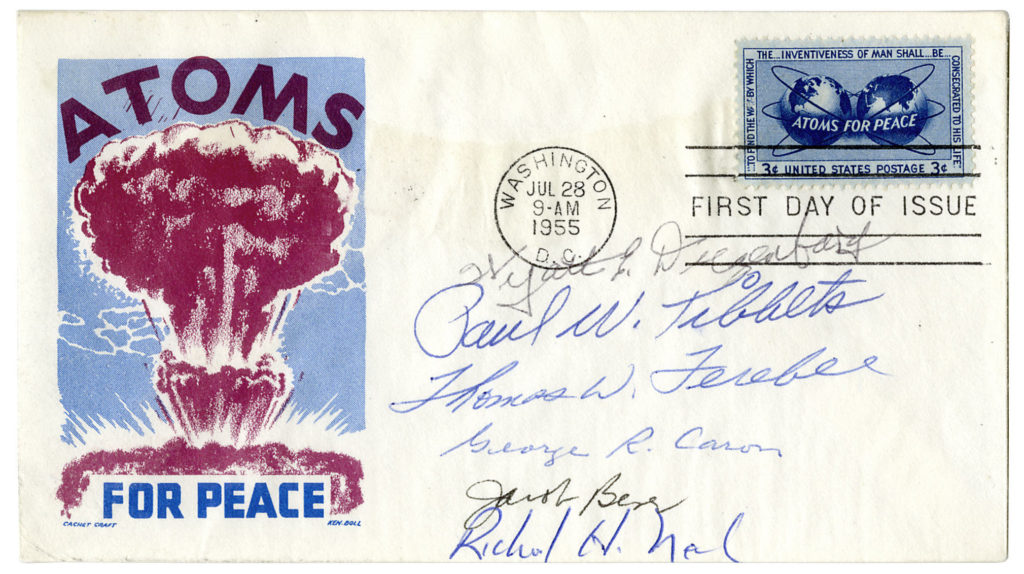

There had even been some giddiness about the Atomic Age. The bar at the National Press Club started serving an “atomic cocktail.” Jewelers sold “atomic earrings” in the shape of a mushroom cloud. General Mills offered an atomic ring and 750,000 children mailed in 15 cents and a cereal box top to “see genuine atoms split to smithereens.”

But the joking masked a growing anxiety that was slowly developing throughout our culture. In the months after it ended the war, the bomb also began to effect an extraordinary philosophical reassessment and generate a gnawing feeling of guilt and fear.

Then, the entire Aug. 31, 1946, issue of The New Yorker magazine was devoted to a 30,000-word article by John Hersey entitled, simply, “Hiroshima.” The writer described the lives of six survivors before, during and after the dropping of the bomb: a young secretary, a tailor’s wife, a German Jesuit missionary, two doctors and a Japanese Methodist minister.

The power of Hersey’s reporting, devoid of any melodrama, brought human content to an unimaginable tragedy and the response was overwhelming. The magazine sold out. A book version became a runaway bestseller (still in print). Albert Einstein bought 1,000 copies and distributed them to friends. An audience of millions tuned in to hear the piece, in its entirety, over the ABC radio network.

After Hersey’s book with its explicit description of the atomic horror (“Their faces wholly burned, their eye sockets were hollow, the fluid from their melted eyes had run down on their cheeks”), it was impossible to ever see the bomb as just another weapon. The only solace was that only America possessed this terrible weapon.

However, it soon became clear that it was only a matter of time before the knowledge would spread and atomic warfare between nations would become possible. People were confronted for the first time of the real possibility of human extinction. They finally grasped the fact that the next war could indeed be what Woodrow Wilson had dreamed the First World War would be – a war to end all wars – although only because it would likely end life itself.

Let’s hope our world leaders develop a consensus about the Korean Peninsula (perhaps reunification) before further escalation. It is time to end this threat, before it has a chance to end us.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is President and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as Chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is President and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as Chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].