By Jim O’Neal

Immigration is back in the news and it’s easy to forget this is not the first time. Out of the enormous industrial growth in the middle of the 19th century came an almost insatiable appetite for unskilled labor. The result was a tremendous wave of immigration, landing 26 million here between 1870 and 1920. They came from all over the world.

However, this was a new kind of immigrant, fashioned for an industrial society, and it made traditionalists uneasy, just as Thomas Jefferson had once been uncertain about the mixing of the American population. Prominent economists voiced concerns about people wholly incompetent as pioneers mixing with independent proprietors and threatening the democratic theories of the founders.

In 1870, over half of Americans toiled on the farm (close to Jefferson’s vision of yeoman farmers) and yet in the first decade of the 20th century, two-thirds of workers were in factories – semi-intelligent work described by Henry Ford as a job “the most stupid man could learn in two days.” The old immigrants of home-seekers had become new immigrants of job-seekers. A nativist movement was inspired to protect America for people of Anglo-Saxon stock.

This was not the first expression of this sentiment. In the 1850s, a secret society in New York City, the Order of the Star Spangled Banner, morphed into the Know-Nothing Party, which inveighed against the arrival of Irish and German Catholics and with them “popish alliances.” Although the Know-Nothings disappeared after 1860, the tendency toward defining Americans according to ethnicity came roaring back after the Civil War.

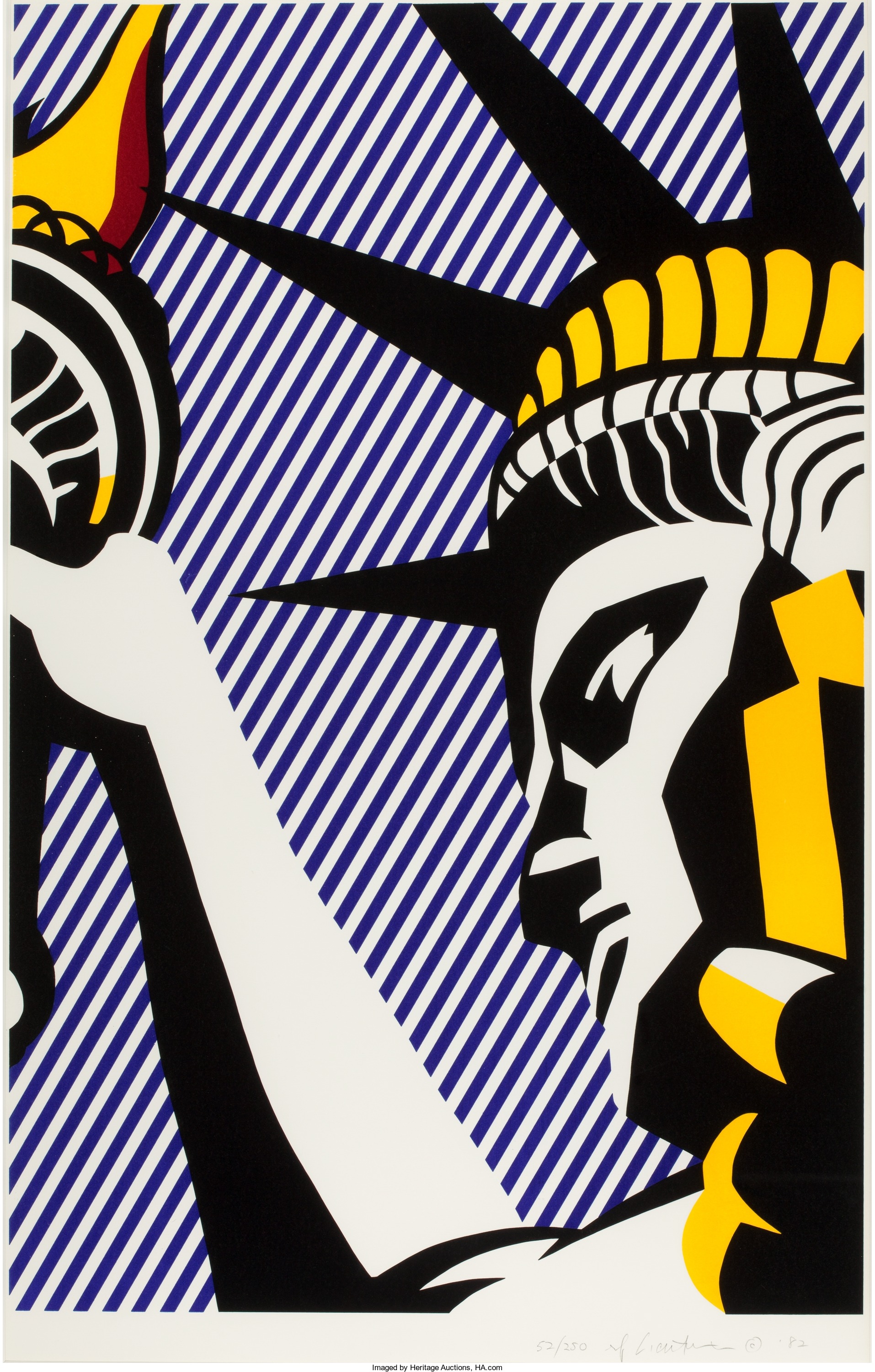

Today, we hold up the Statue of Liberty as our beacon to the world, but it was originally intended to be a symbolic gift from sculptor Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi over admiration for American liberties, not a statement about immigration. It was only after Emma Lazarus’ give-me-your-tired sonnet was added to the statue 17 years later that the image of America as an asylum for the oppressed and poor of the world would emerge.

And even this was followed by the Espionage Act of 1917 and Sedition Act of 1918, which allowed the government to prosecute pacifists, socialists and left-wing organizations, all of which had sizable immigrant followers. Then the Johnson-Reed Act of 1924 imposed strict quotas to preserve America as an Anglo-Saxon nation. For the next 40 years, immigration slowed to a trickle and in the 1930s there were years when more people left America than came to live here.

It is a complicated story, but we have thrived as a nation due to the many, many contributions of immigrants. I predict this controversy too shall pass … as it has every time in the past.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].