By Jim O’Neal

We live on a landmass currently called North America that is relatively young in its present incarnation with most estimates in the range of 200 million years. In periods before, a large portion of it was called Laurentia, which drifted across the equator joining and separating from supercontinents in various collisions that shaped it. There are thick layers of sedimentary rocks that are up to 2 billion years old. Eventually, it was surrounded by ocean and anti-passive margins (i.e. no boundaries by tectonic plates). Then an island chain slammed into it, raising mountain ranges. For perspective, the Appalachians were as tall and majestic as today’s Himalayas.

For tens of millions of years, there was not a single human being in North America, primarily because it was covered by a thick sheet of ice and it was before mankind had evolved. As the Ice Age ebbed, adventurous souls began walking across land bridges as glacial movements changed the landscape. There were multiple migrations in and out of other areas of the world, but people who moved into the Americas were generally on a one-way ticket. In modern times, there is no consensus on who “discovered” America first.

North American exploration spans an entire millennium, with the Vikings in Newfoundland circa 1000 A.D. through England’s colonization on the Atlantic Coast in the 17th century. Spain and Portugal squabbled over the discoveries of Juan Ponce de León and Vasco da Gama, as France and the Netherlands had their own claims to litigate. But our America is really a British story starting with Jamestown, Va. (1607) that gradually grew into 13 colonies. They grew tired of the English yoke and declared independence in 1776 and conquered the British Army in a well-known story of revolution. They formed a somewhat imperfect union called the United States of America, with a constitution and a smallish national government that is still struggling with the line between states’ rights.

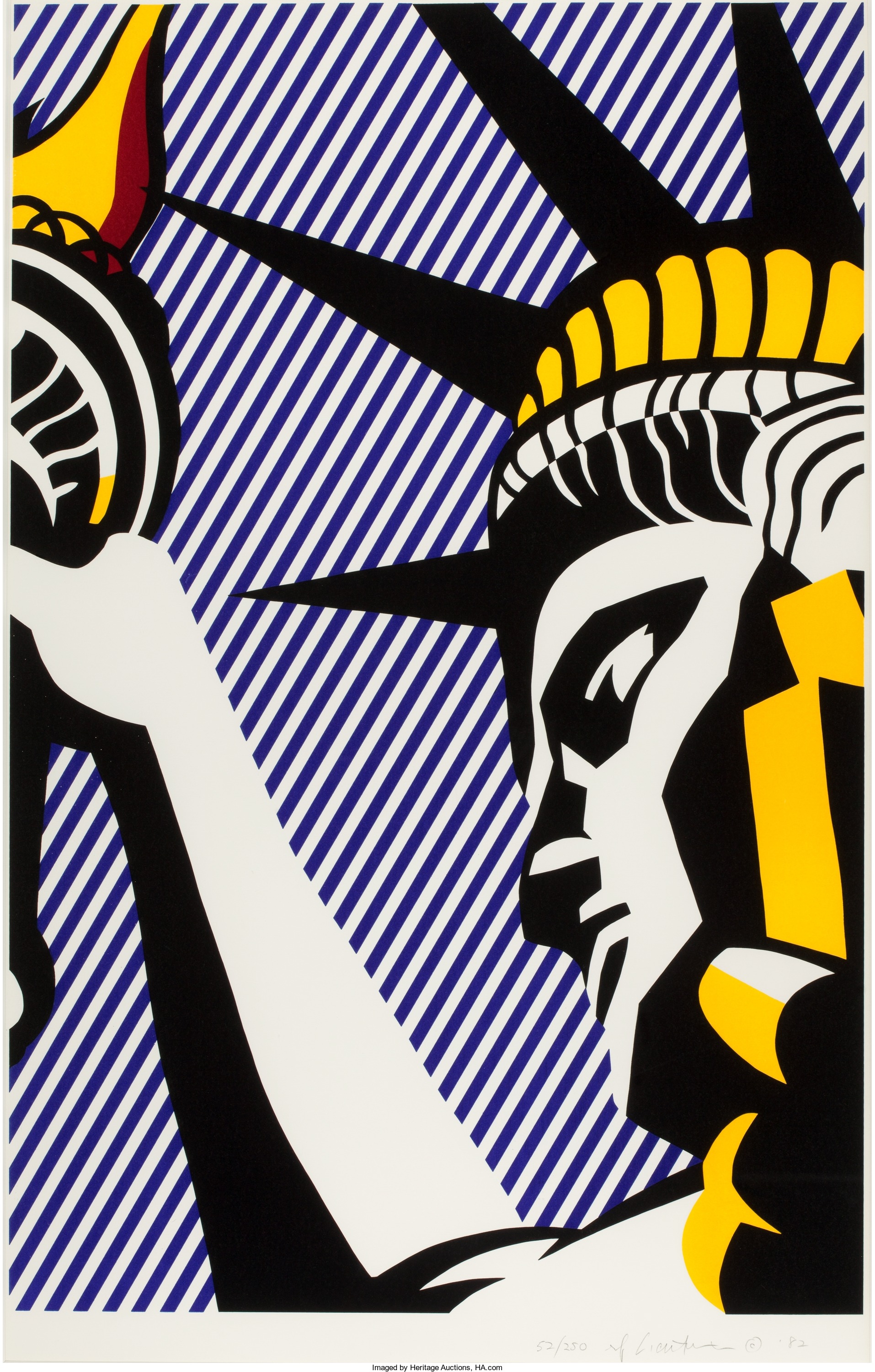

French sculptor Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi attended the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Bartholdi had a strong personal passion for the concepts of independence, liberty and self-determination. He became a member of the Franco-American Union organization and suggested a massive statue to commemorate the American Revolution and a century of friendship between our two countries. A national fundraising campaign was launched that included traditional contributions, as well as fundraising auctions, lotteries and even boxing exhibitions.

Bartholdi collaborated with engineer Gustave Eiffel to build a 305-foot-tall copper and iron statue, and after completion, it was disassembled for shipment to the United States. Finally, on June 17, 1885, the dismantled statue – 350 individual pieces in 200-plus cases – arrived in New York Harbor. It was a fitting gift, emblematic of the friendship between the French and American people. It was formally dedicated the following year in a ceremony presided over by President Grover Cleveland, who said, “We will not forget that Liberty has here made her home; nor shall her chosen altar be neglected.” The statue was dubbed “Liberty Enlightening the World.”

In 1892, Ellis Island opened as America’s chief immigration station and for the next six-plus decades, the statue looked over more than 12 million immigrants who came to find the freedom they were seeking and the “Streets of Gold” in NYC. A plaque inscribed with a sonnet titled “The New Colossus” was placed on an interior wall in 1903. It had been written 20 years earlier by the poet Emma Lazarus.

Gustave Eiffel was given little credit, despite having built virtually the whole interior of what would become the Statue of Liberty and he vowed not to make that mistake again. Perhaps that is why his magnificent Paris landmark is simply an incredible skeleton framework with none of the conventional sheathing of most tall structures of that era.

One thing is certain: We may not know who discovered America first, but there is little doubt that whoever follows us will be aware of what those few people huddled along the East Coast 400 years ago were able to accomplish. Maybe Elon Musk will have a colony on Mars that is still functioning when the ice or oceans envelop Earth again.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].