By Jim O’Neal

A follow-up to my previous post:

The North had a tough time raising money for the war as well. After the defeat at Bull Run, they suffered a new crisis: the collapse of the bond market. Under the Constitution, the U.S. House of Representatives had responsibilities for originating all revenue measures and under pressure from Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase started considering legislation to raise taxes. Ways and Means started with tariffs, but a storm of criticism erupted since it would fall on the poor who needed tea, coffee, sugar and whiskey.

The next option was real estate via “direct taxes,” but Congress objected by noting that wealth in stocks and bonds was excluded, which meant the wealthy could escape paying any taxes quite easily. The more Congress debated the property tax the louder the opposition became. U.S. Rep. Schuyler Colfax from Indiana (a future Republican vice president) said, “I cannot go home and tell my constituents I voted for a bill that would allow a man, a millionaire, who has put his entire property in stock, to be exempt from taxation, while a farmer who lives by his side must pay a tax!” Colfax proposed a tax on stocks, bonds, mortgages and interest on money – and income earned from them. An income tax (inevitably).

U.S. Rep. Thomas Edwards from New Hampshire proposed calling the new tax something other than a direct tax. “Why should we not impose the burdens which are to fall on this country equally, in proportion to their ability to pay them?” An amendment was passed imposing a 3 percent tax on incomes over $600 per year. Someone quoted John Milton in Paradise Lost – he compared the taxpayer to Adam and Eve, driven by necessity “from our untaxed garden, to rely upon the sweat of our brow for support.” An income tax it was.

Secretary Chase was skeptical. He doubted merely labelling the income tax to be indirect would not make it constitutional. More importantly, there were no provisions made for a bureaucratic or enforcement mechanism. The income tax was not collectible. Since it was only a recommendation, he ignored it since he was far too busy with the need to borrow money for the war. As banks were all reluctant to loan a shaky government any money, he turned to a young Philadelphia banker, Jay Cooke, who had a scheme to market the government debt to the public, with Cooke taking a sales commission.

They finally got a consortium of 39 banks to loan $150 million in gold to be paid in three $50 million installments for sale to private individuals. The first $50 million barely sold and the second round failed completely, which killed the scheme. By Dec. 30, 1861, the banks were so stressed they were forced to stop honoring gold payments to their other customers, which was almost tantamount to becoming insolvent.

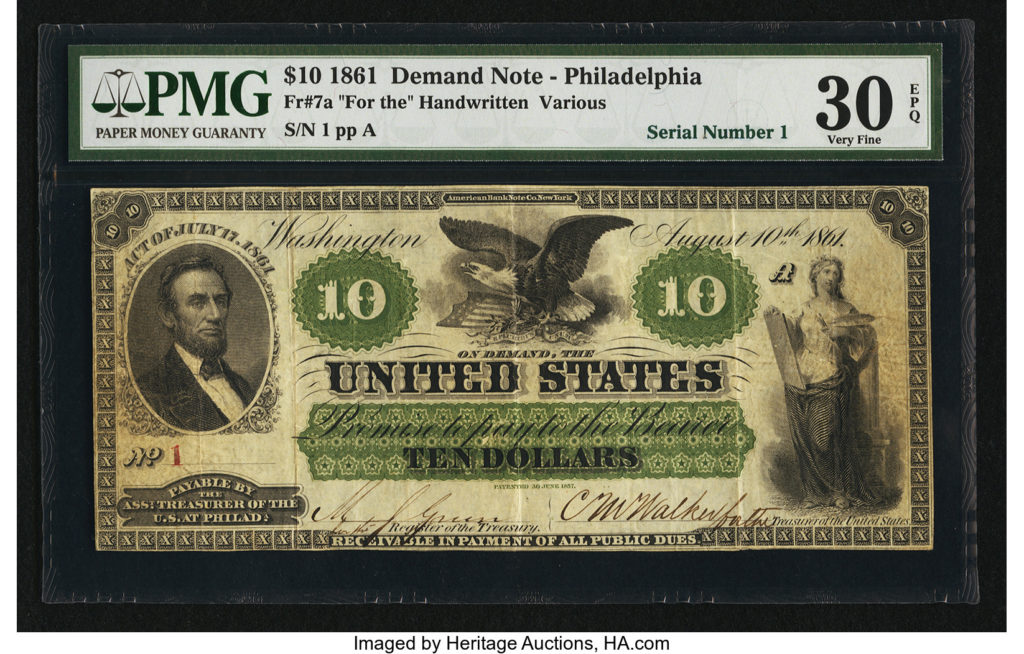

By the start of 1862, Chase realized he had grossly underestimated the costs of the war. His new estimate for year one was $530 million and the assumed revenues from taxes, tariffs and other schemes were falling short and the Treasury funds were almost depleted. New taxes or loans could not possibly fill the gap in time. With no other alternatives available, Chase and President Lincoln overcame their misgivings and endorsed the idea of simply printing money – $50 million in green paper money that the government would just declare to be valid legal tender, though not redeemable in gold or silver.

Then Congress passed the Legal Tender Act in February 1862, providing for $150 million in currency that became known as greenbacks – the first paper money ever issued by the U.S. government … a practice that continues today as the debt has exceeded $20 trillion and seems to be accelerating. I hope to be around to see how it ends.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].