By Jim O’Neal

President Theodore “Teddy” Roosevelt created the U.S. Department of Commerce and Labor on Feb. 14, 1903. It was renamed the Department of Commerce in 1913 and various bureaus and agencies specializing in labor were shifted to a new Department of Labor.

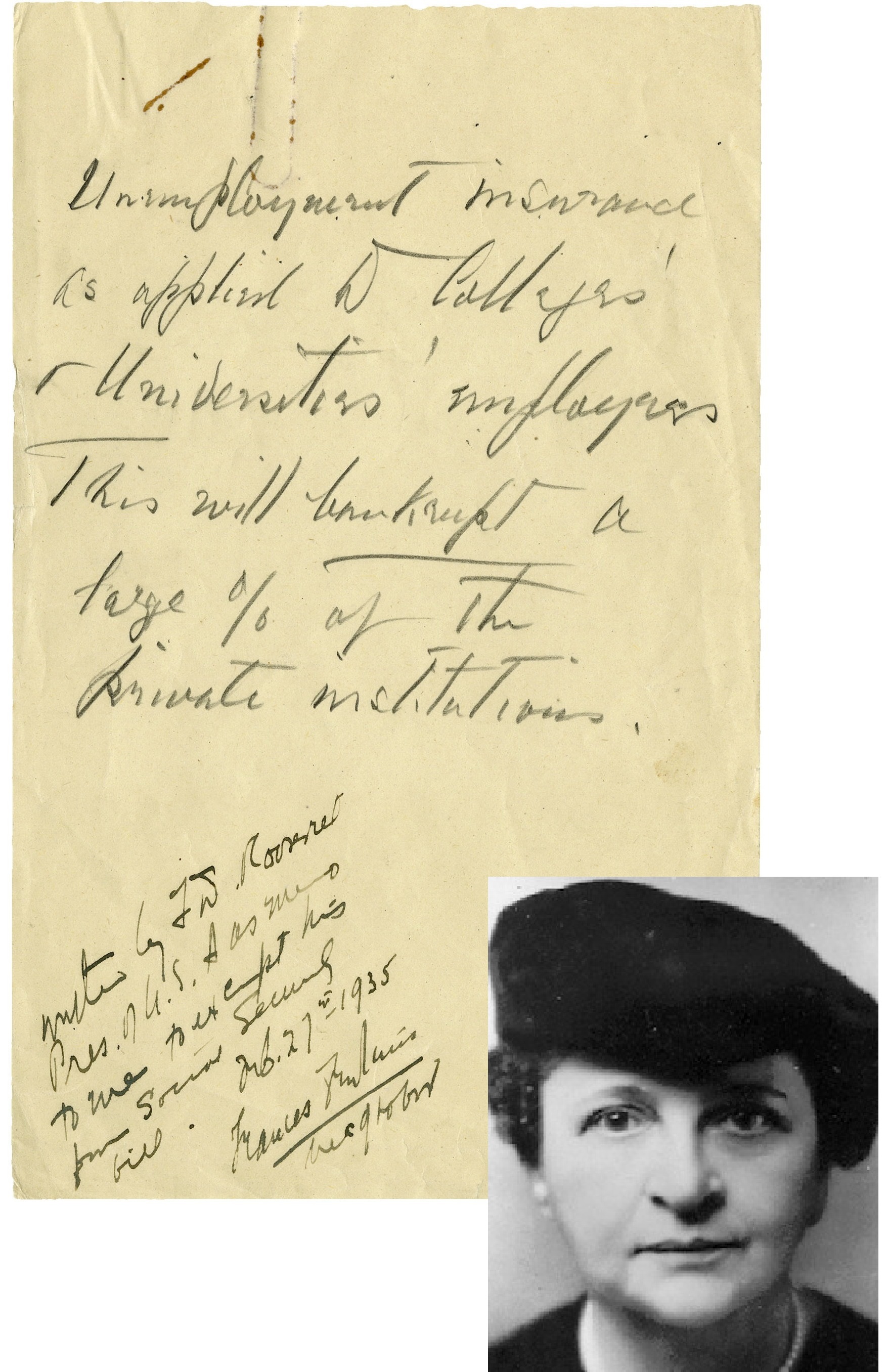

Until 1920, women were prohibited from having Cabinet-level positions since they were not allowed to vote. President Franklin D. Roosevelt broke this barrier in 1933 by appointing Francis Perkins as Secretary of Labor. She was instrumental in aligning labor with the New Deal.

The New Deal was a complex integrated plan to provide present relief, future stability and permanent security in the United States. Much of the president’s thinking about security – which would soon come to be called “social security” – rested on a premise that overcompetition in the labor market depressed wages, spread misery rather than income, curtailed the economy and worked special hardship on the elderly.

Roosevelt was determined to find a way to “dispose of surplus workers,” in particular those over the age of 65. The federal government could provide immediate relief to able-bodied workers as the employer of last resort, while returning welfare functions to the states. Unemployment insurance would relieve damage from economic downturns by sustaining workers’ living standards, and removing older workers (permanently) through government paid old-age pensions would create broad economic stability.

The longer-term features of Roosevelt’s grand design were incorporated into a landmark measure whose legacy endured and reshaped the texture of American life: the Social Security Act. No other New Deal measure proved more lastingly consequential or is more emblematic of the very essence of the New Deal. No one was better prepared to thread the needle of the tortuous legislative process than Secretary of Labor Francis Perkins and FDR personally assigned her the task of chairing a Cabinet committee to prepare the legislation for submission to Congress.

Madame Secretary (as she preferred to be called) brought to her task the commonsense practicality of her New England forebearers; compassion of the special milieu from her time at social-work pioneer Jane Addams’ Hull House; and a dose of political expertise gained as a labor lobbyist and industrial commissioner in New York. Perkins had evolved from a romantic Mount Holyoke College graduate, who tried to sell “true love” stories to pulp magazines, into a mature, deadly serious battler for the underprivileged.

She owed her position to a comrade-in-arms relationship with New York Governor Al Smith and FDR in New York reform battles and also the spreading influence of an organized women’s faction in the Democratic Party. She wisely believed that enlightened middle-class reformers could do more for themselves through tough legislation than union organization; and without the distraction of industrial conflict and social disruption.

Meanwhile, the American labor movement, led by the stubborn Samuel Gompers, relied exclusively on protection of labor’s right to organize. Even after his death, his American Federation of Labor (AFL) spurned legislation and continued to bargain piecemeal, union by union, shop by shop … a strategy that collapsed as the depression deepened.

We know how this ended on Jan. 17, 1935, when President Roosevelt unveiled his Social Security program. Today, 61 million people – or one family in four – receive benefits. However, there is no “lockbox” for Social Security and the flow of taxes and benefit payments are co-mingled with all General Obligations; which includes Medicare, military spending, food stamps and foreign aid. Everything is dependent on the federal government’s ability to levy taxes and borrow money to fund the unsustainable debts backed by “the full faith and credit of the United States.”

Some say that when it comes to global sovereign debt, we live in the best house on Bankrupt Street. However, I am willing to bet that FDR’s cherished Social Security program will never be touched. Francis Perkins did a superb job of getting this concept engrained in a special way and she must still be smiling. She liked her work and served for 12 years and one month – almost a record. James “Tama Jim” Wilson holds that distinction, serving as Secretary of Agricultural from 1897 to 1913, the only Cabinet member to serve under four consecutive presidents, counting the one day he served under Woodrow Wilson.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].