By Jim O’Neal

The Benjamin Franklin House is a formal museum in Central London near Trafalgar Square. It’s a popular location for kooky political speeches and peaceful demonstrations. Although anyone is free to speak about virtually anything, many visitors are not raptly paying attention, preferring to instead feed the pigeons. I never had the temerity to practice my public speaking, although I’m sometimes tempted (“Going wobbly,” as my English friends would observe).

Known once as Charing Cross, Trafalgar Square now commemorates the British naval victory in October 1805 off the coast of Cape Trafalgar, Spain. Admiral Horatio Nelson defeated the Spanish and French fleets there, resulting in Britain gaining global sea supremacy for the next century.

The Franklin House is reputedly the only building still standing where Franklin actually lived … anywhere. He resided there for several years after accepting a diplomatic role from the Pennsylvania Assembly in pre-Revolutionary times. Derelict for most of the 20th century, the site caused a stir 20-plus years ago while it was being renovated. During the extensive excavation, a cache of several hundred human bones were unearthed

Since anatomy was one of the few scientific things Franklin did not dabble in, the general consensus was that one of his colleagues did, at a time when privately dissecting cadavers was unlawful and those who did it were very discreet. I discovered the museum while riding a black cab on the way to the American Bar at the nearby Savoy Hotel. I may take the full tour if we ever return to London.

However, my personal favorite is likely to remain the Franklin Institute in the middle of Philadelphia. A large rotunda features the official national memorial to Franklin: a 20-foot marble statue sculpted by James Earle Fraser in 1938. It was dedicated by Vice President Nelson Aldrich Rockefeller in 1976. Fraser is well known in the worlds of sculpting, medals and coin collecting. He designed the Indian Head (Buffalo) nickel, minted from 1913-38; several key dates in high grade have sold for more than $100,000 at auction. I’ve owned several nice ones, including the popular 3-Leg variety that was minted in Denver in 1937. (Don’t bother checking your change!).

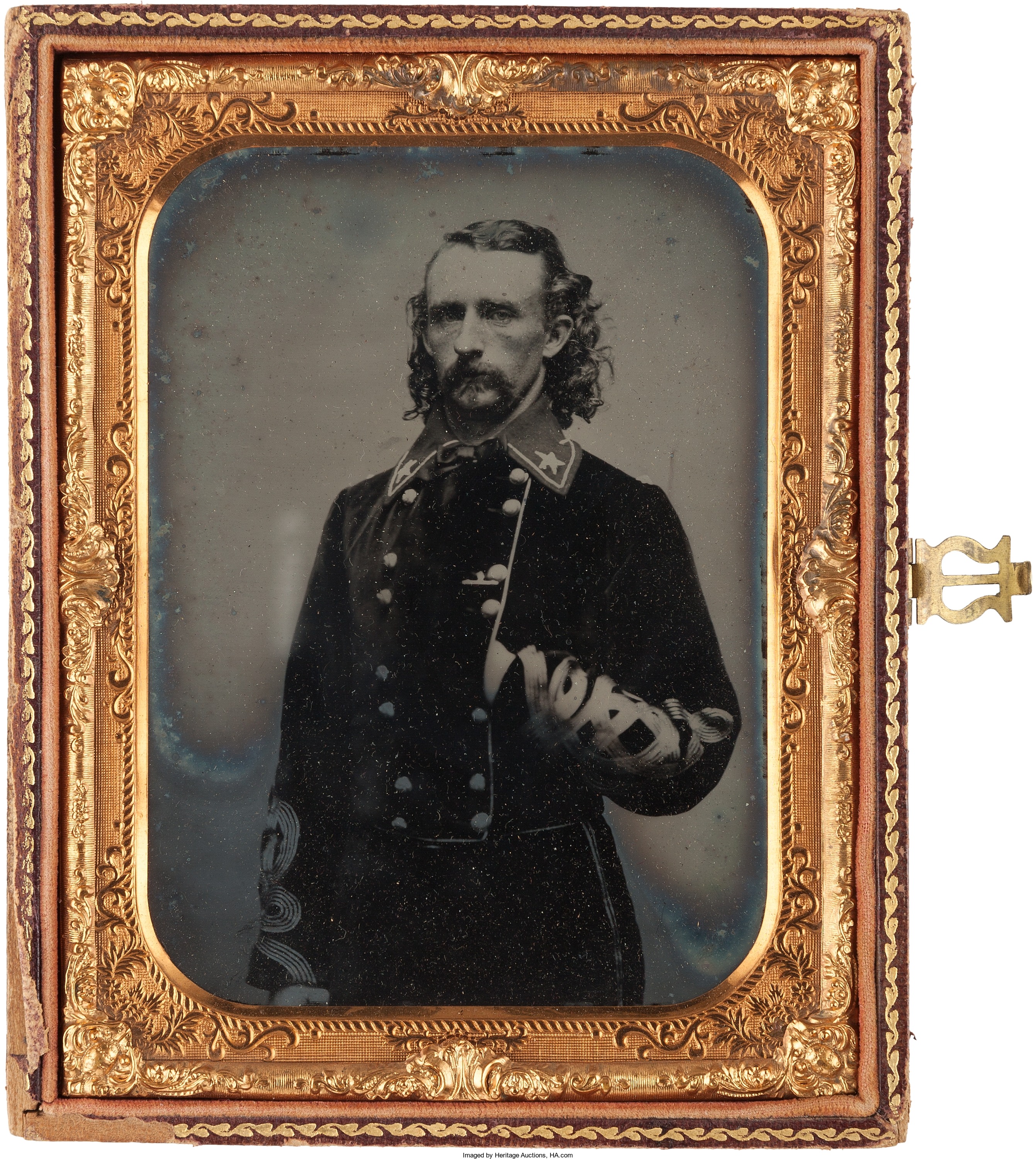

Fraser (1876-1953) grew up in the West and his father, an engineer, was one of the men asked to help retrieve remains from Custer’s Last Stand. George Armstrong Custer needs no introduction due to his famous massacre by the Lakota, Cheyenne and Arapaho in 1876 – the year Fraser was born – in the Battle of the Little Bighorn (Montana). But it helps explain his empathy for American Indians as they were forced off their reservations. His famous statue titled End of the Trail depicts the despair in a dramatic and memorable way. The Beach Boys used it for the cover of their 1971 album Surf’s Up.

Another historic Fraser sculpture is 1940’s Equestrian Statue of Theodore Roosevelt at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New York City. Roosevelt is on horseback with an American Indian standing on one side and an African-American man on the other. The AMNH was built using private funds, including from TR’s father, and it is an outstanding world-class facility in a terrific location across from Central Park.

However, there is a movement to have Roosevelt’s statue removed, with activists claiming it is racist and emblematic of the theft of land by Europeans. Another group has been active throwing red paint on the statue while a commission appointed by Mayor Bill de Blasio studies how to respond to the seemingly endless efforts to erase history. Apparently, the city’s Columbus Circle and its controversial namesake have dropped off the radar screen.

JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].