By Jim O’Neal

T.J. Stiles’ new book Custer’s Trials: A Life on the Frontier of a New America is being praised for the author’s ability to cut through decades of “revisionist baggage,” change the camera’s angle and examine Custer’s life as actually lived … to better gauge the man, his times and his “larger meaning” (whatever that means).

I’m a skeptic, but since Stiles’ biography on Cornelius Vanderbilt was brilliant (winning the Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award), I will probably Kindle it anyway.

What I know is that on the morning of June 25, 1876, Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer and 210 members of the 7th Cavalry (including two brothers) were killed by the Lakota Sioux and Northern Cheyenne.

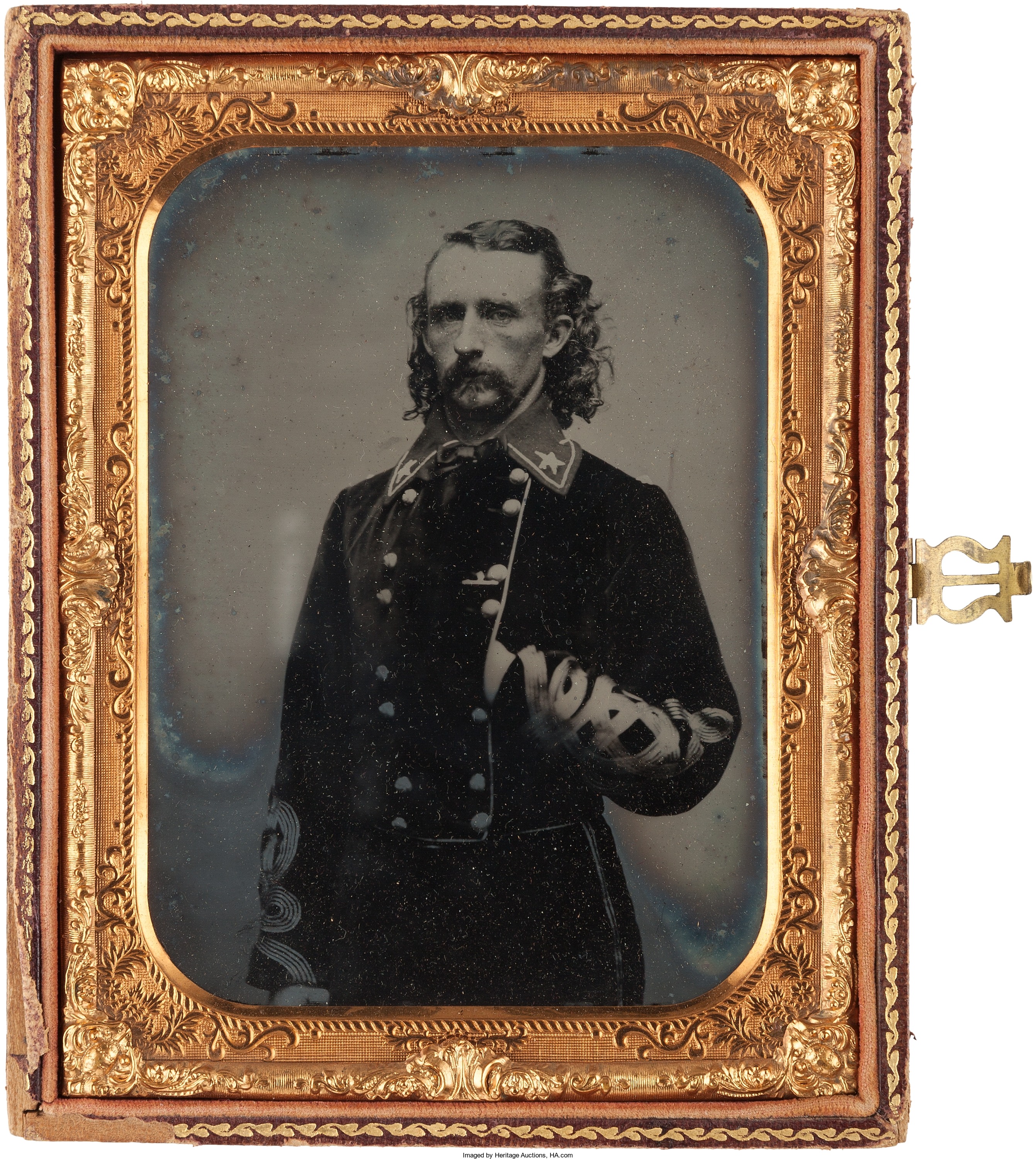

Custer was born in Ohio in 1839, was lucky not to be expelled from West Point (he finished last in his class of 34 cadets) and had a decent career in the Civil War. He was probably indifferent to the issue of slavery and appears to be the type that thrived on war … like so many others of that period.

He undoubtedly loved being called “The Boy General.” With his long, blond hair, he was “the synonym of dashing gallantry and unfaltering fidelity” – at least according to The New York Times.

As a failed business speculator, the war offered him a perfect fit for his ambition and many wondered what he might do if he survived. The answer was quite simple: more war.

But this time, the Plains Indians were aggressively defending the land ceded to them by the Second Treaty of Fort Laramie.

In return for a cessation of attacks against miners and other settlers, the federal government gave the Sioux much of western South Dakota and eastern Wyoming. They also pledged to keep others away from the Sioux’s sacred Paha Sapa, or Black Hills.

However, in 1876 gold was discovered in the Black Hills and soon a hoard of 15,000 miners swarmed the territory. President Grant sent troops to push the Indians farther west and this put the Sioux on a direct collision course with Custer.

The Battle of the Little Big Horn, or “Custer’s Last Stand,” is now legendary, but the larger point is that this single event marked the beginning of the end for the thousands of Sioux warriors involved. In fact, it also included all of the Indian peoples of America.

Following the defeat, public outcry turned Custer into a martyr whose spilt blood had to be avenged. An expanded Army fiercely hounded the great Sioux leader Sitting Bull (he escaped to Canada) and his people. Most of the Sioux surrendered and ended up on reservations.

Within 15 years of Custer’s death, the battles had all faded into legend … waiting patiently to be revived by filmmakers, biographers and blog writers.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is President and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as Chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is President and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as Chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].