“General Grant stood by me when I was crazy and I stood by him when he was drunk. Today we stand by each other.” – Paraphrasing General William Tecumseh Sherman

By Jim O’Neal

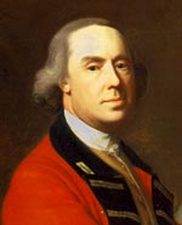

Among the towering figures of the Civil War, none is more enigmatic than General W.T. Sherman. Widely denounced as fiendishly destructive for his infamous “March to the Sea” across Georgia, Sherman was a brilliant commander and strategist who helped bring the bloody war to a faster and surer end. Yet he left a legacy of “total war” against unarmed civilians and their property that has haunted military leaders and many Americans to the present time.

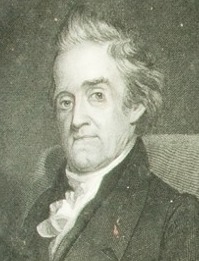

William Tecumseh Sherman (1820-1891) was born in a simple frame house in Lancaster, Ohio, the sixth of 11 children. His father died suddenly in 1829 and the 9-year-old boy was forced to live with his more affluent neighbors, the Ewings, since his mother was destitute. Thomas Ewing Sr. was a senator, Secretary of the Treasury, and the first Secretary of the Interior for presidents Zachary Taylor and Millard Fillmore.

Ewing used his influence to get Sherman into West Point, where he finished sixth in his 1840 class. He left the Army along with many other officers when it seemed civilian life offered a greater chance for success. After a string of failures in banking, real estate and law, Sherman was in Louisiana just before the war began, running a military academy that would later become the foundation for Louisiana State University.

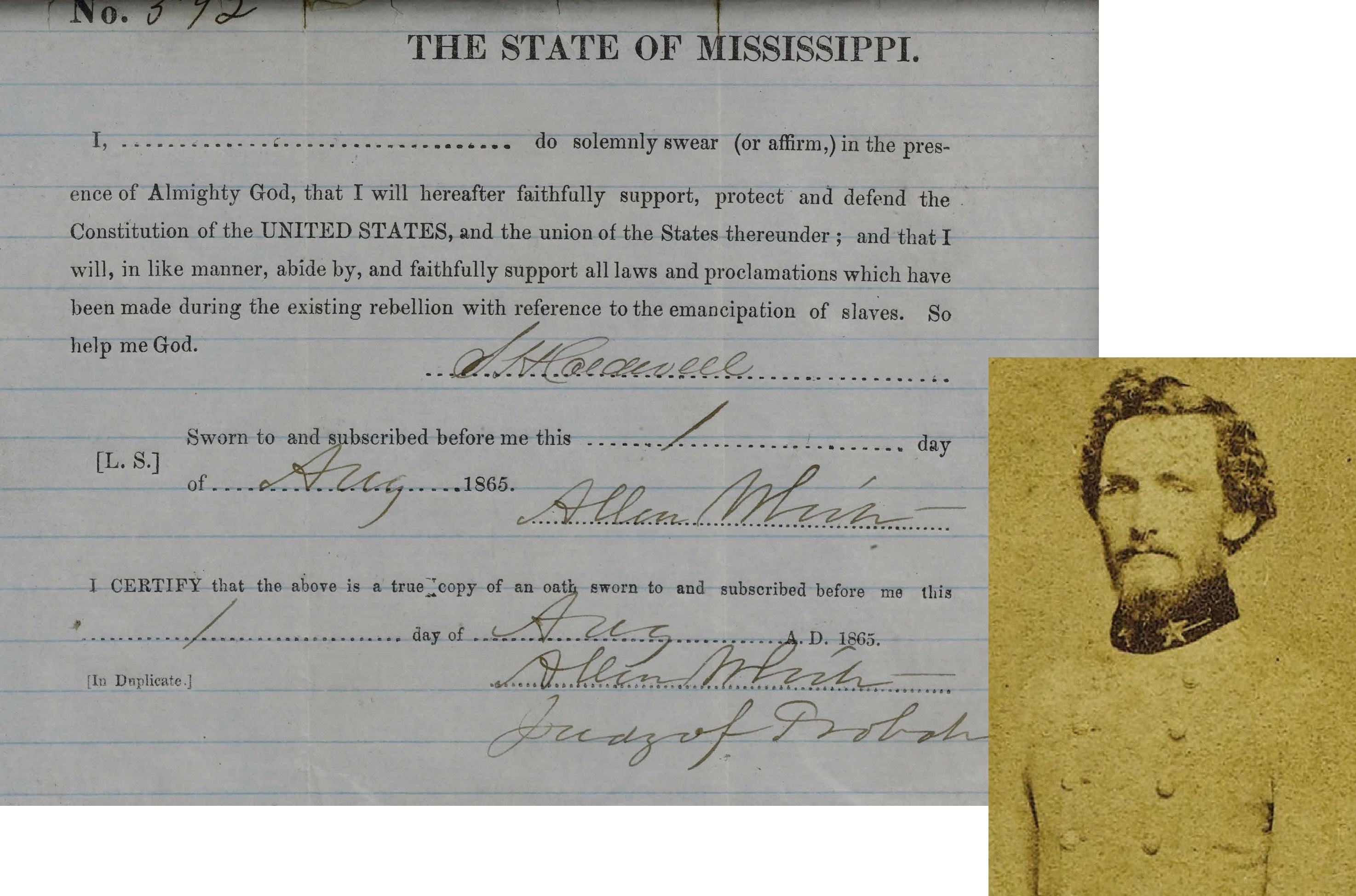

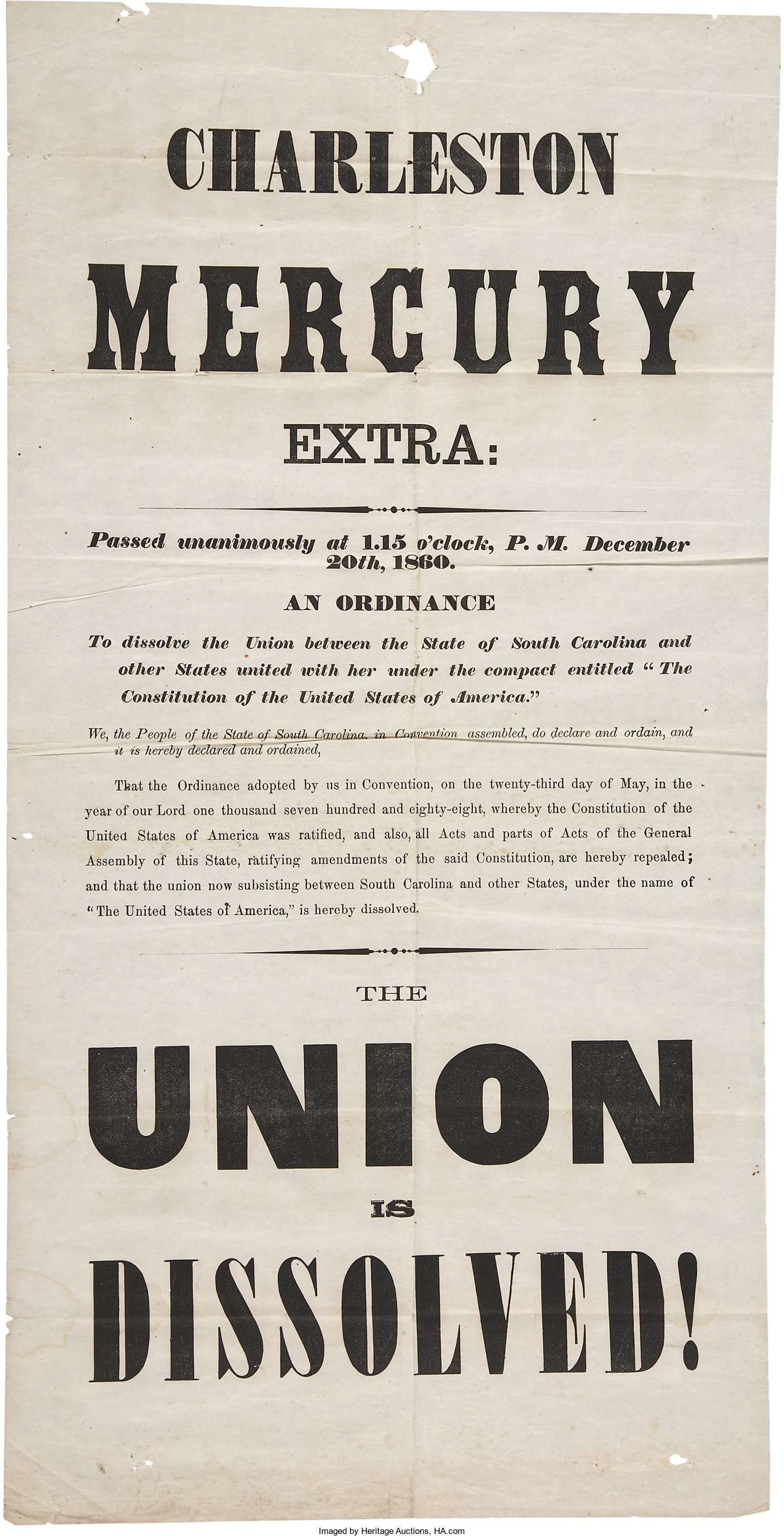

Though he had great friendships with many who joined the Confederacy and had no moral qualms about slavery, Sherman shared the view of many professional soldiers that secession was treason. He returned to Missouri when Louisiana seceded.

When the Civil War arrived right on schedule, one only has to read his comments to appreciate his insight and candor: “You people of the South don’t know what you are doing. This country will be drenched in blood, and God only knows how it will end. It is all folly. Madness. A crime against civilization! You people speak so lightly of war; you don’t know what you are talking about. War is a terrible thing. You mistake, too, the people of the North … you are rushing into war with one of the most powerful, ingeniously mechanical and determined people on Earth – right at your doors. You are bound to fail!”

And fail they did.

But it was more than a lost war. So great was the sense of gloom that some wondered if we could ever reconcile. Over 620,000 lay dead – 1/12 of the North and a staggering 20 percent of the South. It was more battle deaths than all of our nation’s other wars combined. An astonishing two-thirds of Southern wealth simply disappeared, but the more daunting challenge was the emotional carnage and pure generational hatred. Said one woman rather simply: “Oh, how I hate the Yankees. I could trample on their dead bodies and spit on them forever.”

Psychologists who have studied the impact of natural disasters on society – earthquakes, hurricanes, fires and floods – speak bleakly of a broad and terrible social numbing that occurs, afflicting not simply those directly affected, but whole generations living in a disastrous, merciless waste. It is impossible to measure the full-fledged effect on the Southern psyche … their incoherent grief, their land diseased, their way of life obliterated – all without a cure.

Yet today, we still see the scars and do little to avoid the current generation of schisms that are being fed by forces seemingly determined to divide us … the most blessed people that have ever lived on this tiny planet. Tsk, tsk on us.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].