By Jim O’Neal

After serving two full terms as president (1789-97), George Washington was more than ready to leave Philadelphia, where he had lived since relocating from New York City. He returned to his home in Mount Vernon with a profound sense of relief. The plantation had been losing money during his extended absence, leaving him in a financial quandary of being relatively wealthy but cash-poor. Virtually all of his assets were in non-liquid land and slaves.

However, little did he expect that his successor, Vice President John Adams, would allow relations with France to deteriorate to the point of a possible war. Diplomacy had failed and on July 4, 1798, President Adams was forced to offer Washington a commission as Lieutenant General and Commander-in-Chief of the Army with the responsibility of preparing for a potential war. Washington accepted, but wisely delegated the actual work to his trusted friend Alexander Hamilton. All of this happened a mere 17 months before his death at his beloved Mount Vernon.

War with France was avoided, but President Adams utilized some highly controversial tactics, including the Alien and Sedition Acts. These consisted of four bills passed by a highly partisan, Federalist-dominated Congress that were signed into law by Adams in 1798.

Although neither France nor the United States actually declared war, rumors of enemy spies (aliens) or a surprise French invasion frightened many Americans and the Alien Acts were designed to mitigate the risk. The first law, the Naturalization Act, extended the time it took immigrants to gain citizenship from five to 14 years. Another law provided that once war was declared, all male citizens of an enemy nation could be expelled. It was estimated that this would include 25,000 French citizens in the United States. The president also was authorized to deport any non-citizens suspected of plotting against the government during wartime or peace.

The Sedition Act was much more insidious. Sedition means inciting others to resist or rebel against lawful authority. The act first outlawed conspiracies “to oppose any measure of the government.” Further, it made it illegal for anyone to “express any false, scandalous and malicious writing against Congress or the President.” It included published words that had BAD INTENT to DEFAME the government or cause HATRED of the people toward it.

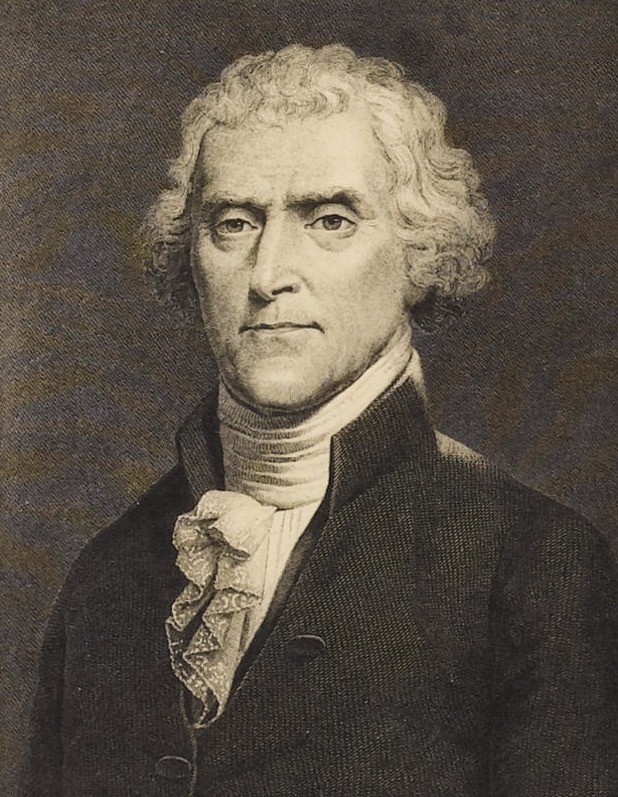

Secretary of State Timothy Pickering was in charge of enforcement and pored over newspapers looking for evidence. Numerous people were indicted, fined and jailed to the point that it became a major issue in the presidential election of 1800. Thomas Jefferson argued the laws violated the First Amendment.

The voters settled the debate by electing Jefferson.

In his inaugural address, Jefferson confirmed a new definition of free speech and press as the right of Americans “to think freely and to speak and write what they think.”

The U.S. Supreme Court never decided whether the Alien and Sedition Acts were constitutional. The laws, quite conveniently, expired on March 3, 1801, John Adams’ last day in office.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is President and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as Chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is President and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as Chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].