By Jim O’Neal

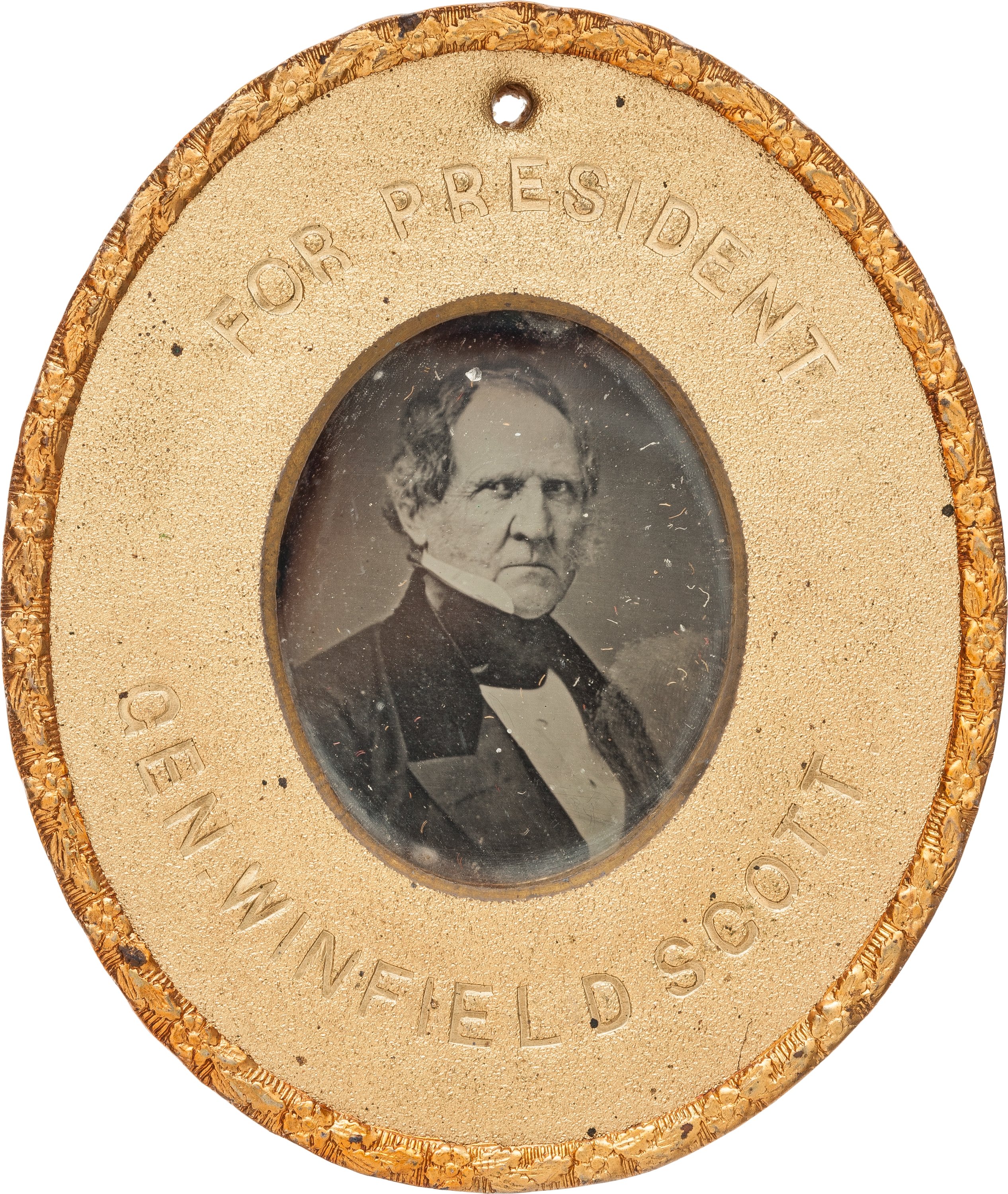

Some historians have labeled him as remarkable, perhaps the most remarkable in American history. For more than 50 years, he served as an officer in the U.S. Army, wearing the stars of a general from 1814 until his death in 1866 at age 80. Following Andrew Jackson’s retirement from the Army in 1821, he served as the country’s most prominent general, stepping down in late 1861, six months after the start of the Civil War.

Lieutenant General Winfield Scott, hero of the War of 1812, conqueror of Mexico in a hazardous campaign, and Abraham Lincoln’s top soldier at the beginning of the Civil War, was born in Virginia in 1786. It was a time of “an innumerable crowd of those striving to escape from their original social condition,” as described by French observer of America, Alexis de Tocqueville.

Success rested on the possession of land, driving both ambitious Americans and their government west.

Winfield’s father died when he was 5, and his mother died in 1803 when he was 17 and on his own. By 1807, he had tired of schooling and joined a prominent law firm in Richmond, “riding the circuits” where he helped provide legal assistance to litigants. It was here that the governor of Virginia made an appeal for volunteers to the state militia after a British frigate intercepted an American ship to search for four deserters from His Majesty’s Navy … the famous Chesapeake-Leopard Affair.

The people of the United States reacted with surprising violence, almost lynching British officers and attacking a nearby squadron. “For the first time in their history,” wrote American historian Henry Adams, “the people of the United States learned in June 1807 the feeling of a true national emotion.”

Public opinion forced President Thomas Jefferson to issue a proclamation requiring all armed British vessels to depart American waters. Then he called on all governors to furnish forces of 100 militia each. Winfield Scott felt an overwhelming urge to play a part and eagerly joined his fellow Virginians.

Thus began a long, storied military career, both during the consolidation of the nation and its expansion.

As a general, he was not the architect. It was President James Madison who attempted to unsuccessfully annex Canada in 1812. It was President Jackson who decided that American Indians east of the Mississippi must be moved to western lands following the passage of the Indian Removal Act of 1830 (the infamous “Trail of Tears”). President John Tyler eventually settled the boundary dispute with Britain over the border between Maine and New Brunswick, Canada. James K. Polk manipulated the War with Mexico that expanded the nation into the southwest. And President James Buchanan used General Scott to secure the San Juan Islands, between Vancouver Island and the mainland, during the Pig War between the United States and Great Britain.

For each of these presidents, the agent and builder, in contrast to the architect, was General Scott. In this role, Scott served under 14 presidents, 13 of them as a general officer. Winfield “Old Fuss and Feathers” Scott lost his own bid for the presidency as the unsuccessful candidate for the Whigs in 1852. However, he certainly had the longest and most astonishing military career in U.S. history. And that includes all the other great men: Washington, Jackson, Grant, Lee, Eisenhower, etc.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].