By Jim O’Neal

Rome, “The Eternal City,” began as a cluster of small villages on seven hills by the River Tiber and grew into a city-state. According to legend, it was first ruled by kings, who were overthrown, before becoming a republic. A new constitution allowed the election of two senators to run the state. Their terms were limited to one year, as the office of king was prohibited.

It became remarkably successful between 500 and 300 B.C., extending its power through conquest and diplomacy until it encompassed the whole of Italy. By 120 B.C., Rome dominated parts of North Africa, the Iberian Peninsula, Greece and Southern France. The conquered territories were organized into provinces ruled by short-term governors who maintained order and ensured the collection of taxes.

By the 1st century B.C., Rome was a Mediterranean superpower, yet its long tradition of collective government, in which no individual could gain much control, was challenged by the personal ambitions of a few immensely powerful military men. A series of civil wars and unrest culminated in the dictatorship of Julius Caesar, a brilliant general and statesman.

Gaius Julius Caesar was born in Rome in 100 B.C. to a family of distinguished ancestry. From an early age, he grasped that money was the key to power in a political system that had become hopelessly corrupt. He also learned that forging a network of alliances and patronage would be crucial to his success.

After serving in the war to crush the slave revolt led by Spartacus, he returned to Rome in 60 B.C. and spent vast sums of money buying influence and positions. Eventually, he teamed up with two other powerful Romans, Crassus and Pompey, to form the First Triumvirate. Then Caesar was first consul and two years later, governor of Gaul, which gave him a springboard to true military glory.

Over the next eight years, he conquered Gaul, bringing the whole of France, parts of Germany, and Belgium under his personal rule. Buoyed by his achievements, he then tried to dictate the terms for returning to Rome. Roman laws required military leaders to relinquish control of their armies before returning to Rome, a prerequisite for running for public office.

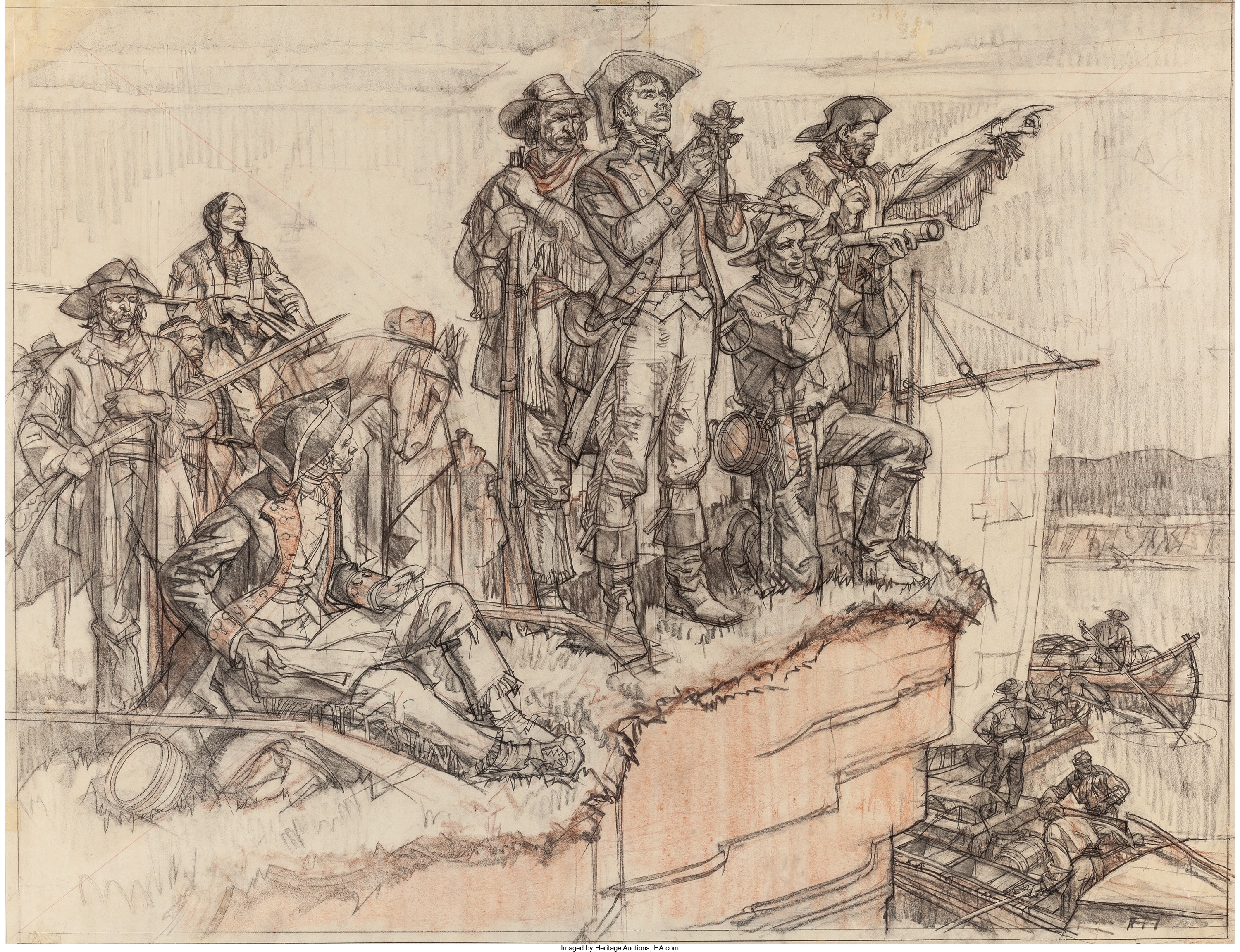

When Caesar refused, the Roman Senate declared him hostis (public enemy) and then came the unthinkable: He decided to march his army on Rome! En route, he paused at the border between the Gallic provinces and Italy proper … a small river called the Rubicon. Acutely aware that crossing that river would constitute a declaration of war, he announced “alea iacta est” (the die is cast) and led his army forward, telling them, “Even yet we may draw back, but once across that little bridge, and the whole issue is with the sword.”

“Crossing the Rubicon” is still in vogue today and represents making a difficult decision that cannot be reversed once taken.

Obviously, Caesar won the ensuing civil war, but soon a conspiracy developed with 60 senators planning to assassinate him on March 15, 44 B.C. (the infamous “Ides of March”). What is curious is that even after more than 2,000 years, we find Caesar references so often. The latest is the flap over a play in NYC’s Central Park, Julius Caesar, in which the title character bears a not-so-subtle resemblance to President Trump, with The New York Times questioning whether he can survive living in Caesar’s Palace.

Et tu, Brute?

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].