By Jim O’Neal

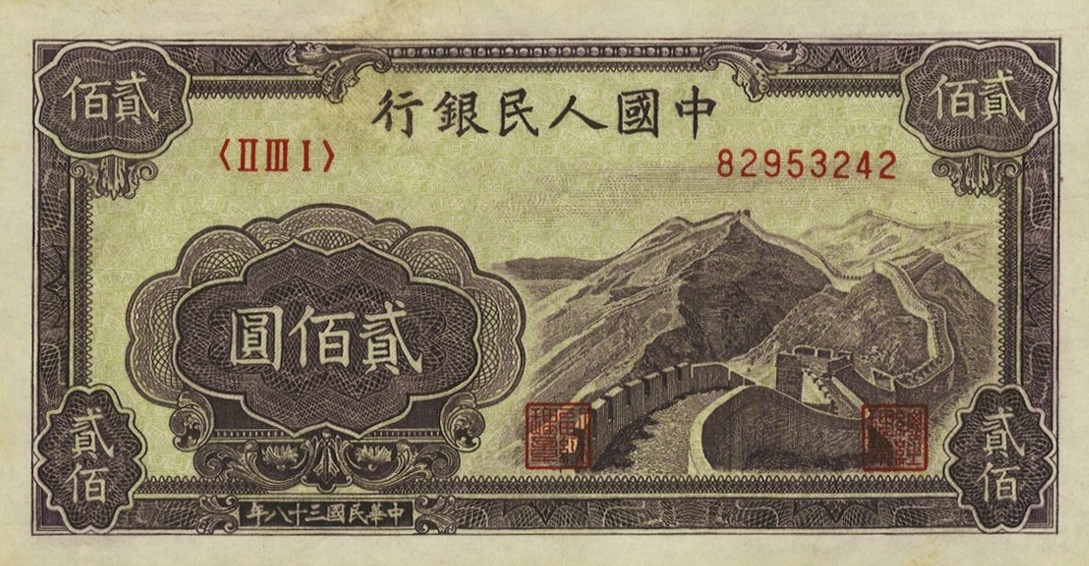

One of the Great Walls of China dates to 200 B.C., intended as a protective barrier for its inhabitants rather than a way to restrict the movement of people. The concept surfaced again in the Ming Dynasty era in the 14th century. The Chinese have always preferred a closed societal culture … until the 20th century, when they discovered the advantages of low-cost labor to produce goods for export.

Conversion of a strategic asset like low-cost labor to generate capital for economic development becomes more feasible with every technology improvement. The competitive advantages among nations has evolved into a “flat world” (Tom Friedman) that economists typically call globalization.

However, we still have nations like Japan, which strongly prefers a monoculture (similar to a beehive) and relegates foreigners to service roles. As an island nation with a strong navy, they can implement immigration policies that are enforceable. The rub is that birth rates are so low and the population increasingly aging that their economy has been stagnant for 20-plus years.

Europeans who migrated here in the early 16th century did not have to worry about physical barriers to entry. Their challenges were primarily in crossing the dangerous Atlantic Ocean and then surviving in a new, uncivilized land. The Pilgrims (English Separatists) came from Plymouth, England, via the Mayflower in 1620. They were joined by Puritans, who established the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Many were seeking religious freedom, fame and fortune, or simply personal freedom.

When the U.S. Constitution was adopted on Sept. 17, 1787, it expressly gave Congress the power to establish a uniform rule of naturalization. In 1790, they passed the Naturalization Act, which enabled those with two-year residency to apply for citizenship. However, it was restricted to “free white people” of good moral character. In 1795, it was modified to five-year residency and a three-year notification clause. A 1798 Act increased residency to 14 years and notice of intent to five years.

In 1802, Congress passed the Naturalization Law – “free white” retained – alien intent to three years – residency to five years – resident children included – ditto children abroad – former British soldiers barred from citizenship.

This was the last real major act of naturalization in the 19th century, except in 1870, when it was opened to African-Americans. But in the 20th century, the game changed. The U.S. focus changed from legislation that regulated immigration to restrictions. The Immigration Act of 1917 included literacy tests and barred immigration from the Asia-Pacific Zone. It dramatically increased the list of “undesirables” – alcoholics, idiots, those with contagious diseases, and political radicals. The “Barred Zone” included much of Asia and the Pacific Islands.

The Immigration Act of 1924 severely restricted the immigration of Africans and banned immigration of Arabs and Asians. In 1986, the Immigration Reform and Control Act was designed to be the final solution. Four million undocumented workers got a path to citizenship in return for “border security.” It was never fully implemented.

Build a wall? Sure, no problem. Solve the issue? Two hundred years of American history says probably not.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].